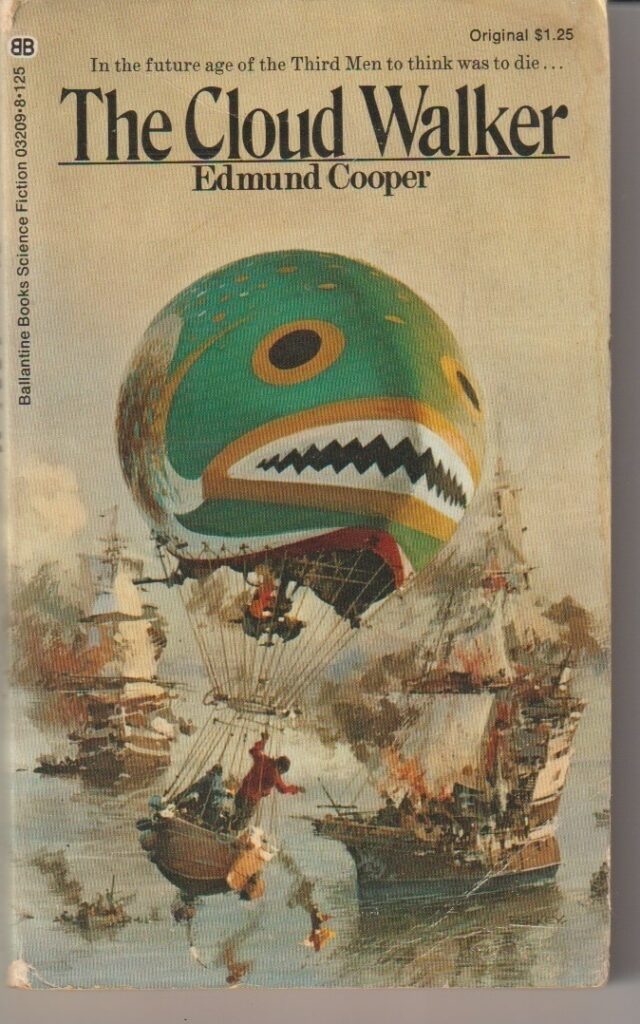

I first read Edmund Cooper’s novel The Cloud Walker in my 20s, shortly after it was published in 1973. And I enjoyed it. Reading it now, nearly half a century later, I enjoyed it, but maybe with a difference or two

The setting of the science fiction book is England at some future date after the First Men (us) destroyed themselves and devastated civilization — and after their successors, the Second Men, who rediscovered everything that had been lost in terms of science and technology, had destroyed themselves as well — and after the Third Men have arisen with a strong aversion to the science and technology.

Indeed, in this future England, central power is controlled by the Church of the Sacred Hammer which holds that any “unnecessary” machine is immoral and heretical and that anyone who creates such an apparatus needs to burn at the stake. All for the greater glory of Ludd!

Ned Ludd

I suspect that The Cloud Walker was the place I first learned of the Luddites who, as a note explains at the start of the novel, went on a rampage in 1811-12 and again in 1816 destroying all sorts of machines, such as power looms and stocking frames. It was a protest against the Industrial Revolution.

They derived their name from Ned Ludd, an idiot boy in Leicestershire, who, it is said, unable to catch someone who had been tormenting him, destroyed some stocking frames in a fit of temper (1779).

In this future England, Ned Ludd has evolved into the Divine Boy who, back in his day, “was taken and crucified” for attacking machines but is now recognized as a kind of god. At least, the Church of the Sacred Hammer does a lot of smiting and burning in his name.

All of this would have entranced the twenty-something me since, with the dogmatism of youth, I was certain that the progress of human civilization was something that should be celebrated, not destroyed.

Now, I’m not so sure. Look at how life has changed because some bright guy in Silicon Valley turned the cellphone into a computer. Think of all the efforts to push the idea of artificial intelligence as far as it will go — and the real-world implications of such efforts. And think about the significance of genetic engineering on humanity.

“This wild talk”

Cooper’s novel tells the story of Kieron Joinerson (the son of the joiner) who, at the age of five, decides on what his life task will be and, at the age of eight, reveals his plan to eight-year-old Petrina, his fiancé under a contract between the two families.

“I shall construct a flying machine.”

Petrina turned pale. “A flying machine. Kieron, be careful. It is all right to speak of such things to me. I shall be your wife. I shall bear your children. But do not talk of flying machines to anyone else, especially the dominie and the neddy (of the Church)…”

“They don’t burn children now. Even you should know that.”

“But they still burn men, and one day you will be a man. They burned a farmer in Chichester two summers ago for devising a machine to cut his wheat…You make me feel cold with this wild talk.”

Truth be told, Kieron is a bit loose with his talk, and, later, he is somewhat devil-may-care about the consequences of actually building a machine. In fact, he fashions a huge kite with which he rides through the air until he falls, breaking his leg and bringing himself to the notice of the church fathers. Then, he constructs an even larger hot-air balloon which floats on the wind over his town of Arundel where it explodes into a fireball, raining down debris on the castle of Seigneur Fitzalan.

Blurt out

Although Kieron has the secret love of the Seigneur’s daughter Alyx, he is quickly chained up in a dungeon by the Church, facing the real possibility of being burned at the stake.

In many ways, I was a fairly risk-averse young man so I imagine that, reading The Cloud Walker, I felt that Kieron was pretty stupid to blurt out his desire to fly to so many people and to carry out his experiments in a way that would be difficult to hide.

Now, I’m not so sure. From the perspective of seven decades, I have a better sense of how someone with an idea — a joyful challenge and a heady dream — wouldn’t want to hide it under a bushel basket, even if it were politic to do so.

It’s not as if someone with an idea has to believe that, by explaining it, he or she will be able to convince others and get a free pass to do what needs to be done. No, I suspect that such a person will usually not think it worthwhile to worry about fears — thinking instead that solving the puzzle is so much fun and, in the end, all that counts.

History, certainly, is littered with the bodies of a great many clever people whose ideas about science or religion or culture were blurted out too loudly and got them drawn and quartered, or burned, or hung, or, well, crucified.

“A great surge of confidence and power”

In fact, Kieron’s goose is cooked, in a metaphorical way, inasmuch as the full weight of the Church’s inquisition is about to come down on him.

But, then, a dozen pirate ships arrive at the coast, walk in the four miles to Arundel, sack the town, killing the Seigneur, killing and raping Alyx, killing Kieron’s parents. He survives because he is in the dungeon, but, when he gets out, he is bent on revenge against the freebooters, led by Admiral Death.

The upshot is that Kieron, with the help of the survivors of the town, builds a giant balloon, and, then, with a friend, he rides the balloon on the wind toward the pirate fleet.

For a moment or two, it seemed as if the entire world was a frozen tableau, the only movement being that of the hot-air balloon as it continued to drift and rise slowly. Toy ships lay ahead; toy horsemen were held to the earth below. Kieron experienced a great surge of confidence and power, rejoicing in the silence, the smooth and beautiful movement, rejoicing that he was now free of the element for which he had been born.

To make war

The Cloud Walker is a bracingly vivid and nuanced adventure story, thanks to Cooper’s deft writing. He was a poet and author of dozens of science fiction novels, and he knew how to tell a tale.

My twenty-something self, I suspect, enjoyed the adventure and probably wasn’t troubled by the thoughts that I’m left with after reading this enjoyable book.

Kieron is driven to fly. And the first time he’s able to fly with the approval of his fellow townspeople is when they are under attack by the pirates. And his first flight is to drop fire down upon the wooden decks and fabric sails of the pirate ships.

In other words, his first use of his dream is to make war.

And, of course, the implication at the opening of the novel is that the flying machines of the First Men and Second Men were part of the means through which those civilizations were destroyed. So, in attacking the pirates from the air, is Kieron starting a journey that will lead ultimately to the destruction of the Third Men?

Cooper, who deals with many practical and philosophical issues in The Cloud Walker, doesn’t address this question. And it’s probably unfair to think he would need to.

Yet, it’s there. And I don’t have any answers either.

Perhaps, the bottom line is that anything newly fashioned can be used for war and violence.

Of course, anything old can be too.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.25.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.