In winter night, the boy sits in the dark kitchen of the flat with his grandfather Dzia-Dzia. Upstairs, the pregnant girl Marcy is playing sad Chopin on her piano as Dzia-Dzia follows along, playing an invisible keyboard on the kitchen table.

“Michael, come in here by the heater, or if you’re going to stay in there put the burners on,” Mom called.

I lit the burners on the stove. They hovered in the dark like blue crowns of flame, flickering Dzia-Dzia’s shadow across the walls. His head pitched, his arms flew up as he struck the notes. The walls and windowpanes shook with gusts of wind and music. I imagined plaster dust wafting down, coating the kitchen, a fine network of cracks spreading through the dishes.

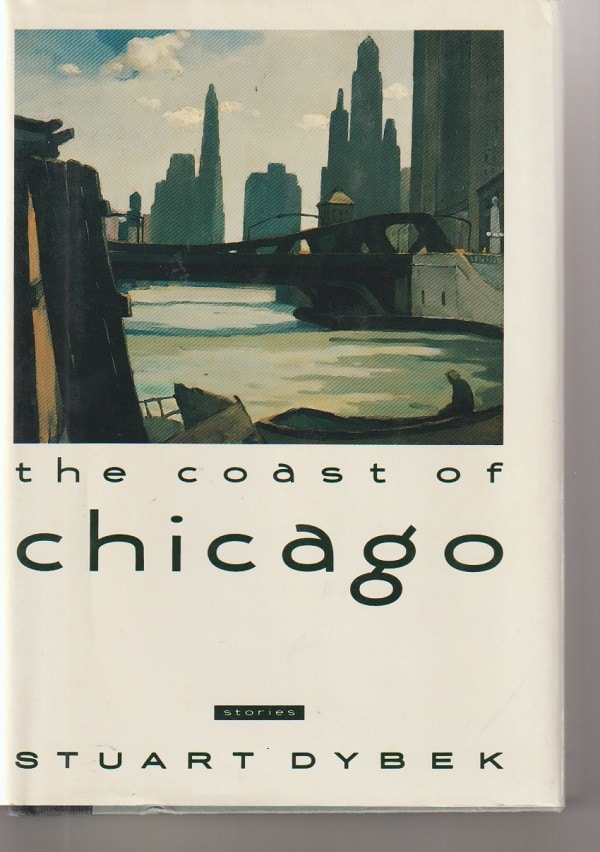

This small moment from “Chopin in Winter” encapsules much of the poignant and often bleak richness of Stuart Dybek’s 1990 short story collection The Coast of Chicago.

A lot of numbers

This collection includes 14 stories, of which five are only a page or two in length. Another five cover four to eight pages each. The remaining four range from 27 to 42 pages.

However, from another perspective, The Coast of Chicago can be seen as an assemblage of 26 stories. That’s because the 36-page “Nighthawks” is made up of nine smaller related stories (averaging four pages each) while the 42-page “Hot Ice” is a grouping of five linked stories (averaging eight pages each). The only long stories are “Blight,” 30 pages, and “Chopin in Winter, 27 pages.

All of this is a lot of numbers, but I think there’s a good reason to look at the underlying infrastructure of this collection.

Consider “Nighthawks.” Any of those nine smaller stories could stand alone, even the two-page “Gold Coast.” After all, Dybek’s collection has five independent stories that short.

But “Gold Coast” doesn’t stand alone. It’s part of a line of tales that are all related in some way to the Edward Hopper painting Nighthawks at the Art Institute of Chicago and to each other. Some share the same characters. A kiss floats through the air in several. A grieving AWOL kid whose girlfriend on angel dust leapt to her death from a rooftop shows up three times.

They don’t tell the same story, but they do.

What’s written and not written

There is method — and poetry — to this jaggedness.

Dybek could have written a long, single-thread story or even a novel built around Hopper’s Nighthawks. Instead, he wrote these nine small tales and grouped together in “Nighthawks,” a disjointed literary collage of many perspectives.

A novel, even in its more modern incarnations, gives the sense of containment, of a beginning, middle and end. It gives the sense that the story it tells is in the control of the writer.

By contrast, “Nighthawks” gives the sense of an infinite number of stories, of which Dybek is telling nine. Each of his tales is a snippet, a moment in time, in the much larger story of its characters.

He is silent on the rest of those larger stories. That’s the key: As important as what Dybek writes is what he doesn’t write.

The words he uses to tell these tales are only as important as the words not written, the myriad other moments in the larger story that are not told. The words he writes give a glimpse into those larger stories, and they hint at everything else that happens in those larger untold stories.

Indeed, at the end of a tale, a reader is all but invited to speculate what happens next….and what happened before.

“Lights!”

And what’s true about “Nighthawks” is also true of The Coast of Chicago. The stories in this collection all have something, at least indirectly, to do with the Pilsen and Little Village neighborhoods of Chicago in the mid-twentieth century and with the changes taking place there at that time and with the feelings of those who lived there about those changes.

The stories, long or short, provide moments. And those moments hint at larger stories that are being lived and give glimpses into those larger stories.

And it’s also true about each individual story, even the very short ones.

Consider “Lights,” a one-page story of a little more than 100 words. It begins:

In summer, waiting for night, we’d pose against the afterglow on corners, watching traffic cruise through the neighborhood. Sometimes, a car would go by without its headlights on and we’d all yell, “Lights!”

The rest of the story tells how drivers, embarrassed, would usually flip on their lights right away but not always. Some, for reasons unclear — perhaps the driver is “lost in that glide to somewhere else” — would continue lightless down the block in the dark, and “we’d hear yelling from doorways and storefronts, front steps, and other corners, voices winking on like fireflies: “Lights! Your lights! Hey, lights!”

In a real way, those hundred-plus words encapsulate the entire history of a neighborhood, its culture, its people, its ethos and its daily life. Cultural anthropologists from a thousand years in the future could read that and, from it, tease out many of the details and realities of a particular moment in a particular community at a particular place on the face of the Earth.

A prose poem

Most of the stories in The Coast of Chicago are entwined in their common focus, in one way or another, on the near southwest side of the city, an Eastern European community being transformed into one that is Mexican.

All of the stories are entwined in their common poetry, such as those phrases among the hundred-plus words of “Lights” — “lost in that glide to somewhere else” and “voices winking on like fireflies.”

You could argue that, with imagery such as that, “Lights” is a tight, contained prose poem. But I think you could also extend that idea to the longer stories and even to the book itself. Each story, in its way, is a prose poem. So, too, is the collection.

“The grotesque richness of nature”

Remember the boy in the kitchen with his grandfather where the burners on the stove “hovered in the dark like blue crowns of flame, flickering Dzia-Dzia’s shadow across the walls.”

Such imagery fills The Coast of Chicago, such as in the long story “Blight” which centers around a group of friends including Deejo:

Of all our indigenous wildlife — sparrows, pigeons, mice, rats, dogs, cats — it was only bugs that suggested the grotesque richness of nature. A lot of kids had, at one time or another, expressed their wonder by torturing them a little. But Deejo had been obsessed. He’d become diabolically adept as a destroyer, the kind of kid who would observe an ant hole for hours, even bait it with a Holloway bar, before blowing it up with a cherry bomb. Then one day his grandpa Tony said, “Hey, Joey, pretty soon they’re gonna invent little microphones and you’ll be able to hear them screaming.”

There is a lot being said here, and it’s not a commentary on the sadistic tendencies of youth.

It has to do with life in this particular neighborhood in midcentury Chicago, an urban place of sidewalks and brick buildings where the natural world — “the grotesque richness of nature” — is encountered not in great vistas or forest paths, but in “our indigenous wildlife,” such as pigeons and bugs.

Dybek uses this poetic phrase to open the door to deeper levels of meaning.

This neighborhood is a place, like most urban places, where a child can get fascinated by the natural world but has to make do with its most mundane of expressions. And where a child can interact with the natural world — can, like a scientist, experiment with the natural world — even if it is an invasive way, such as blowing up an ant hole.

And it is a place where an adult can put that natural world into perspective, can relate it to the child’s life with a lesson that is crystal clear: “Hey, Joey, pretty soon they’re gonna invent little microphones and you’ll be able to hear them screaming.”

It’s a funny comment, but it also sends a clear message. And it suggests how these bugs fit into the world of the neighborhood — and how the neighborhood fits into the larger society.

“The grotesque richness of nature.”

“Such good viaducts”

That boy in the kitchen with his grandfather listening through the ceiling to the girl above playing Chopin — there is a feeling in all of the stories and in The Coast of Chicago as a whole that, on every page, sad, wistful, pensive Chopin music is playing in the background.

In midcentury Chicago, Pilsen and Little Village are old and worn-down communities on the edges of civic consciousness and services. Indeed, they don’t get the attention of Mayor Richard J. Daley and City Hall except to be designated as a blighted area, an area that is so old and worn-down it needs to be torn down and built again.

That’s the subject of the story “Blight” which includes a scene in which three friends from the neighborhood go to a viaduct at the western edge of the neighborhood near Douglas Park to take advantage of the acoustics and sing blues songs with homemade percussion of empty bottles and beer cans and a snapped-off car antenna.

Once, a gang of black kids appeared on the Douglas Park end of the viaduct and stood harmonizing from bass through falsetto just like the Coasters, so sweetly that though at first we tried outshouting them, we finally shut up and listened, except for Pepper who was keeping the beat.

We applauded from our side by stayed where we were, and they stayed on theirs. Douglas Park has become the new boundary after the riots the summer before.

“How can a place with such good viaducts have blight, man?” Pepper asked, still rapping his aerial as we walked back.

“Frankly, man,” Ziggy said, “I always suspected it was a little fucked up around here.”

“Well, that’s different,” Pepper said. “Then let them call it an Official Fucked-Up Neighborhood.”

Imposed on people

Yes, this scene is about the three boys singing together, and about them admiring the singing of the black kids, and about them joking about their neighborhood.

Even more, though, it is about divisions. And it is about divisions that are imposed on people, such as the clear line between the boys’ neighborhood and that of the blacks, a line none of them had a hand in drawing, but a line they live by.

And it’s about the powerlessness of much of life, not just in this “blighted” neighborhood but for anyone alive.

Much of what human beings experience is out of their control. The designation that their neighborhood is blighted — and all the changes that that will bring about on their blocks and in their streets — is not something that these three boys had a voice in. Yet, they live with it. As do we all.

“Snow-clotted”

The wistfulness and melancholy of living a life that is controlled by many outside forces is what connects all of the stories in Dybek’s collection, those set in Pilsen and Little Village and those few which focus on the North Side.

The first story in The Coast of Chicago is “Farwell,” and it is set in the far north neighborhood of Rogers Park — a story of four pages in which the narrator recalls visiting his Russian friend Babovitch at his apartment on Farwell Avenue.

It was a winter night, snowing. His apartment building was the last one on the block where the street dead-ended against the lake. Behind a snow-clotted cyclone fence, the tennis courts were drifted over, and beyond the courts and a small, lakeside park, a white pier extended to a green beacon.

For city people, a heavy snowfall is a routine reminder of how insignificant human beings are in the face of the weather. The landscape Dybek describes is totally in the grip of nature. No one is to be seen.

“No longer existed”

The narrator visits Babovitch, a university teacher who, later, moves when his contract isn’t renewed.

It didn’t surprise me. He’d been on the move since deserting to the British during the War. He’d lived in England, and Canada, and said he never knew where else was next, but that sooner or later staying in one place reminded him that where he belonged no longer existed. He’d lived on Farwell, a street whose name sounded almost like saying goodbye.

Babovitch is very much like all those characters from Pilsen and Little Village in Dybek’s other stories. Very much like Michael’s grandfather Dzia-Dzia whose homeland too is long lost, except for the music of Chopin

Like Babovitch, Dzia-Dzia knew “where he belonged no longer existed.”

Those teens and young men on Chicago’s near southwest side were living in a place that was in the process of existing no longer. Indeed, so much had already changed that the place they’d spent their childhood “no longer existed.” And, in the coming years, even the place they lived in now would cease to exist.

They were as rootless as Babovitch. But, really, aren’t we all?

Patrick T. Reardon

3.4.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.