William M. Stableford’s 1971 transposition of Homer’s Iliad into The Days of Glory is a clever piece of science fiction, especially for a guy who was then in his early 20s.

But maybe it was too clever.

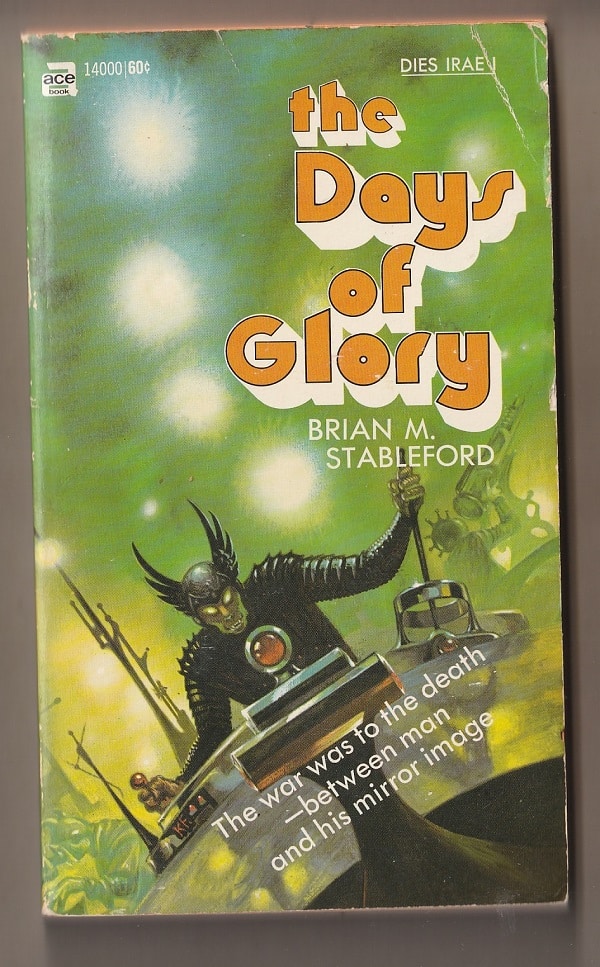

I’m not sure that, half a century ago, many sci-fi readers would have been tempted to pick up the book if they knew it was modeled on the epic poem. In fact, Ace Books didn’t deem the connection much of a selling point — the Iliad isn’t mentioned anywhere on the cover or on the inside of The Days of Glory.

It was because of the Iliad connection that I read Stableford’s book in the last week as part of a lot of Homer-related reading that I’m doing. In fact, I’m planning to read all three volumes in Stableford’s Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) trilogy, the others being In the Kingdom of the Beasts, modeled on the Odyssey, and Day of Wrath.

In many respects, The Days of Glory is fairly close to Homer’s story. There are, as in the Iliad, a lot of speeches. And a lot of bloody violence. And Stableford follows pretty much the general pattern of events although he doesn’t include events from the last couple books of the poem.

For me, the first half of The Days of Glory was more than a bit sluggish, and I think it would have dragged even more for someone who wasn’t looking, as I was, for parallels with the Iliad. The battles in the second half were well done, both those occurring in space and hyperspace and those on the ground with swords, knives, pistols and rifles as weapons.

No Homer

Because of its Iliad connection, the trilogy is mentioned here and there, online and even in at least one academic paper. But, from what I can tell, it was never anything like a bestseller. It doesn’t appear, from what I have been able to determine, that the original editions were ever republished.

One reason for that, perhaps, is that all of Stableford’s efforts to link his trilogy with Homer’s epics may have confused those sci-fi fans who were just looking for a cool adventure story.

Another reason: Fans of the Iliad and Odyssey probably found fault with Stableford’s writing.

For me, it was a bit of a game to watch Stableford tell the Iliad story. Nonetheless, I couldn’t help feeling that the key points in the poem were a great deal blunted in The Days of Glory.

Stableford has had a long and successful career as a science-fiction writer, publishing more than a hundred novels and collections. But, let’s face it, Stableford is no Homer.

Stableford’s scenes were fine, but they paled in contrast to my memory of the scenes in Homer.

The death of Slavesdream

Here’s an example: the death of Slavesdream, the close friend of Stormwind — Stableford’s parallels for Patroclus and Achilles.

In The Days of Glory, the scene is a showdown between Slavesdream and Blackstar (the Hector character), mano a mano. They’ve been fighting and wounding each other for a couple pages, and then Slavesdream swings his axe at Blackstar’s legs:

Blackstar slipped sideways to his knees and leaned back. The axe merely plucked at his clothing and carried straight on. Blackstar had all the time he needed to slip his blade up under Slavesdream’s rib cage, through the diaphragm, and into the stomach.

The Beast lord fell, choking on his own blood.

That’s clear, direct and effective. It’s a shootout at OK Corral. Two heroes, one triumphing.

The death of Patroclus

Homer’s version, however, is much richer in terms of narrative and emotional complexity. And it’s closer to the way war works.

Instead of battling Patroclus one on one, Hector is watching from the ranks as Patroclus is fighting in the midst of a crowd. Then, Hector sees his opening and takes advantage of a lucky moment to put the Greek warrior away.

And, even more, Homer’s version is a work of literary genius. He complicates in a beautiful and terrible way his description of the scene with metaphors that give the death a profound resonance.

Here’s how William Cowper translated the scene in 1791:

Confusion seized [Patroclus’s] brain; his noble limbs/Quaked under him, and panic-stunn’d he stood./Then came a Dardan Chief, who from behind/Enforced a pointed lance into his back/Between the shoulders; Panthus’ son was he,/Euphorbus, famous for equestrian skill,/For spearmanship,…/… He, Patroclus, mighty Chief!/First threw a lance at thee, which yet life/Quell’d not; …/…Then, soon as Hector the retreat perceived/Of brave Patroclus wounded, issuing forth/From his own phalanx, he approach’d and drove/A spear right through his body at the waist./Sounding he fell. Loud groan’d Achaia’s host./As when the lion and the sturdy boar/Contend in battle on the mountain-tops/For some scant rivulet, thirst-parch’d alike,/Ere long the lion quells the panting boar;/So Priameian Hector, spear in hand,/Slew Menœtiades the valiant slayer/Of multitudes, and thus in accents wing’d,/With fierce delight exulted in his fall.

Two other versions

Or consider the translation of W.H.D. Rouse from 1938:

His mind was blinded, his knees crickled under him, he stood there dazed.

Then from behind a spear hit him between the shoulders. A Dardanian struck him, Euphorbos Panthoïdês, best of all his yearsmates in spearmanship and horsemanship and fleetness of foot….His was the first blow, but it did not bring down Patroclos…

When Hector saw him retreating and wounded, he came near and stabbed him in the belly: the blade ran through, he fell with a dull thud, and consternation took the Achaians. So fell Patroclos, like a wild boar killed by a lion, when both are angry and both are parched with thirst, and they fight over a little mountain pool, until the lion is too strong for the panting boar. Patroclos Menoitiadês had killed many men, but Hector Priamidês killed him: and then he vaunted his victory without disguise:

Or this 2006 version from Ian Johnston:

…His mind went blank,/his fine limbs grew limp — he stood there in a daze./ From close behind, Euphorbus, son of Panthous,/a Dardan warrior, hit him in the back,/with a sharp spear between the shoulder blades./Euphorbus surpassed all men the same age as him in spear throwing, horsemanship, and speed on foot….… Euphorbus was the first to strike you, horseman Patroclus, but he failed/to kill you…

But when Hector noticed brave Patroclus going back,/wounded by sharp bronze, he moved up through the ranks,/stood close to Patroclus and struck him with his spear,/low in the stomach, driving the bronze straight through./Patroclus fell with a crash, and Achaea’s army/was filled with anguish. Just as a lion overcomes/a tireless wild boar in combat, when both beasts/fight bravely in the mountains over a small spring/where they both want to drink, and the lion’s strength/brings down the panting boar — that’s how Hector,/moving close in with his spear, destroyed the life/of Menoetius’s noble son, who’d killed so many men. Then Hector spoke winged words of triumph over him.

Homer’s beauty

I acknowledge that this is a bit unfair. Half a century ago, Stableford set out to write some science fiction, using the two Homer epics as a road map. Borrowing from Homer is something that generations upon generations of writers have done, from Dante to James Joyce, and from Virgil to Herman Melville.

He wrote three books. The first one is not terrible and, in fact, somewhat stirring at times. I’ll find out about the other two when I read them.

Stableford wasn’t trying to compete with Homer’s poetry. But it was Homer’s poetry that was in my mind as I read The Days of Glory.

I can’t read Homer’s Greek, but those who can say it’s spectacular. I can only read Homer through the medium of translation which, even if it can’t capture the essential music of the epics, can communicate at least some of its beauty.

That’s what I come away with after looking at these excerpts from three translators.

Such language

There’s Cowper’s lines “who from behind/Enforced a pointed lance into his back/Between the shoulders.” What an odd and wonderful use of “enforced”!

There’s Rouse writing that Patroclus’s “knees crickled under him.” I can’t find the word “crickle” in any dictionary, so maybe Rouse made it up. But, as soon as I hear the sound of the word, I know what it means.

And there’s Johnston translation of an extended simile to say that Hector killed Patroclus “just as a lion overcomes/a tireless wild boar in combat, when both beasts/fight bravely in the mountains over a small spring/where they both want to drink, and the lion’s strength/brings down the panting boar.”

There are many reasons the Iliad and the Odyssey have lived for more than two thousand years. Such language, even in translation, is one of them.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.10.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.