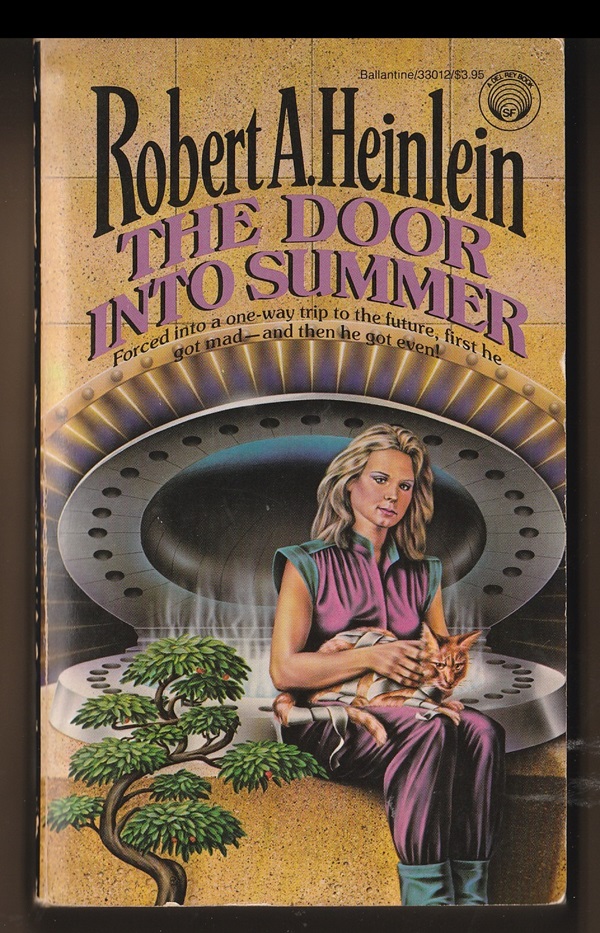

Science fiction can get complicated for authors who focus on the near-term future, as Robert A. Heinlein does in The Door into Summer.

Consider this timeline:

- Heinlein writes the book in 1956.

- The book is set in 1970 but has a time travel element.

- The central character goes into the future to the year 2000.

Fine as far as it goes.

But because books can last a long time — in this case, at least, 68 years — here’s another timeline:

- Heinlein writes the book in 1956.

- The book is set in 1970 but has a time travel element.

- Someone, maybe even me, reads the book in the 1970s and knows that a lot of what Heinlein describes for that era to be false, such as a service that will freeze you for a certain number of years before defrosting you in the future. (I read a whole lot of Heinlein novels in my 20s in that decade, and, while I don’t remember reading this one, I easily could have.)

- The central character goes into the future to the year 2000 (using that freeze service).

- Someone reads the book in the year 2000 and knows that many of Heinlein’s descriptions of 2000 aren’t accurate, such as a huge drop in the price of gold to the point that, now, it’s just another industrial metal.

-

-

- Someone, like me, reads the book in the final days of 2024 and knows that the futures Heinlein describes for 1970 and 2000 were off the mark.

-

It’s not just that Heinlein predicts certain things for 1970 and 2000 that don’t turn out to be true. It’s also that, unavoidably, he misses huge changes in society. For instance, he has nothing in 1970 about hippies and the youth culture and the Vietnam War protests. And he has nothing in 2000 about the internet and cellphones and Y2K.

The question arises: Why would someone in 1970 continue to read The Door into Summer once it became clear that Heinlein’s predictions for that year were off? Why would someone in 2000? Why did I in 2024?

One answer

One answer may be that, at least for a large group of science-fiction readers, the author’s predictions aren’t the main thing.

The main thing for such readers may be for the author to set up an alternative universe, essentially a fantasy world.

As far as the reader in 1956 knows, this alternative place — the world in 1970 — might be exactly as Heinlein describes. The reader in the 1970s knows that it’s not accurate but enjoys the book because it shows how the 1970s might have been. The same could be true for the reader in 2000.

Another answer

Another answer, maybe in tandem with the first, is that the reader in 1970 and in 2000 gets an added thrill from seeing in Heinlein’s book how the image of those future years didn’t match up to the actuality.

So, the reader is given an insight into what the people of the 1950s thought of the future. And that’s a reminder that, at any given moment, any speculation about the future is very iffy at best.

A third answer

The third answer is the main one for me and, I suspect, for a great many of Heinlein’s readers.

The Door into Summer is fun because Heinlein writes so well. He is telling an adventure story with great verve and zest. He pumps the story full of excitement and intrigue, and the reader can’t help but keep turning the pages.

His central character Dan Davis goes from 1970 to 2000 and then back to 1970 and then back to 2000, and Heinlein not only keeps everything straight for the reader but he’s also created a story that hooks the reader early and never lets go.

What if?

It all comes down, I guess, to “what if.”

When he wrote the book, Heinlein imagined what if Dan Davis is living in 1970 and what if he ends up in 2000 (and how would a guy react to a world that’s 30 years in the future) and what if he returns to 1970 (and what might he know how to do from his time in the future) and what if he goes back to 2000 (and what might he want to accomplish).

That’s what Heinlein imagined as a writer. And, because he’s such a good writer, I’m willing as a reader to embrace all of his what-ifs.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.23.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

I would be interested on your review of Edward Bellamy’s “Looking Backward” about the observations of a gentleman who falls asleep in 1887 and wakes up in 2000 in a socialist utopia.

Many years ago, I looked at that book, and my memory is that Bellamy isn’t as good of a writer as Heinlein is.

I always felt that The Door Into Summer was the inspiration for Back To The Future.

Yeah, I can see that.