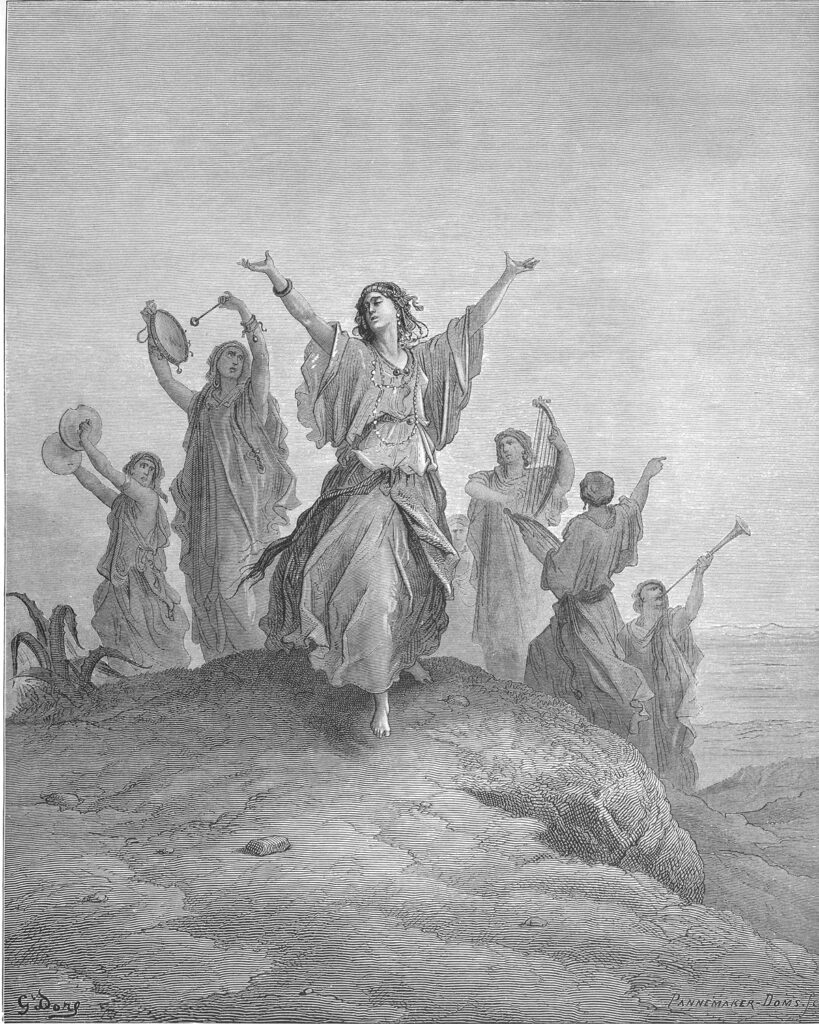

Amid the many scenes of violence, sin and pain that Gustave Dore created to illustrate a mid-nineteenth century Bible, the image of Jephthah’s daughter dancing out to meet her victorious father is delightful, festive and joyful.

And, yet, it isn’t.

The image represents a tragic story that’s told in a few verses in the Book of Judges.

In the midst of battle, Jephthah vows that, if God will let him triumph over the people of Ammon, he will make sure that “whatsoever cometh forth of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, shall surely be the Lord’s, and I will offer it up for a burnt offering.”

Jephthah won the battle, and, then, as it’s written in Judges 11:34-35:

Jephthah came to Mizpeh unto his house, and, behold, his daughter came out to meet him with timbrels and with dances: and she was his only child; beside her he had neither son nor daughter.

And it came to pass, when he saw her, that he rent his clothes, and said, Alas, my daughter! thou hast brought me very low, and thou art one of them that trouble me: for I have opened my mouth unto the Lord, and I cannot go back.

His daughter accepted her fate although Bible scholars aren’t sure what that was. It might have been that she was a human sacrifice, or maybe that she was pledged to the Lord and lived apart from everyone else.

Either way, quite a price to pay for being happy at the return of your father.

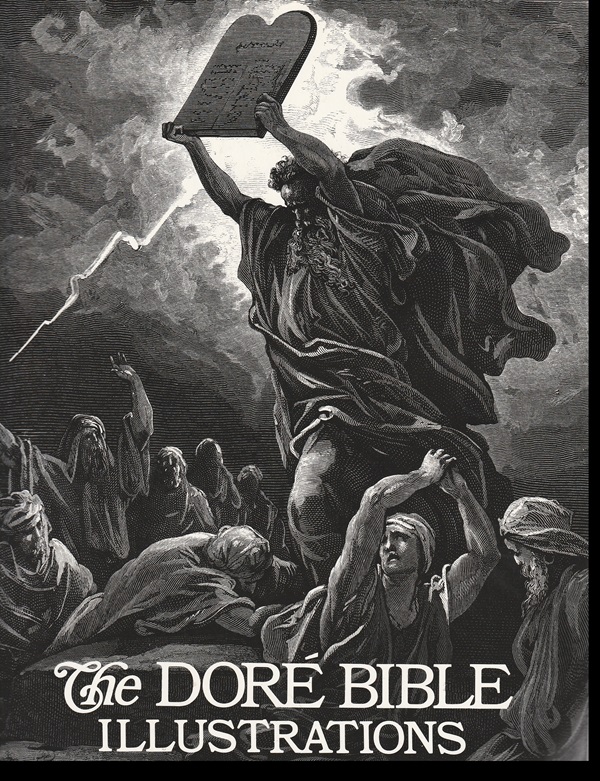

Dore’s Moses

Dore created 241 wood engravings for the deluxe 1843 publication of La Grande Bible de Tours, and they have been hugely popular ever since. Indeed, in 1974, Dover Publications republished them as The Dore Bible Illustrations, a modestly priced large-format book that is still in print.

Over the past century and a half, these engravings have helped shape the way believers and non-believers imagine Bible scenes. For instance, Dore’s image of Moses throwing the two tablets of the laws given to him by God was clearly an inspiration for the 1956 Cecil B. DeMille film The Ten Commandments and for its advertising.

Readers of this book, I suspect, gravitate initially to the biblical scenes they find most inspiring or revealing or striking. At least that’s what I did.

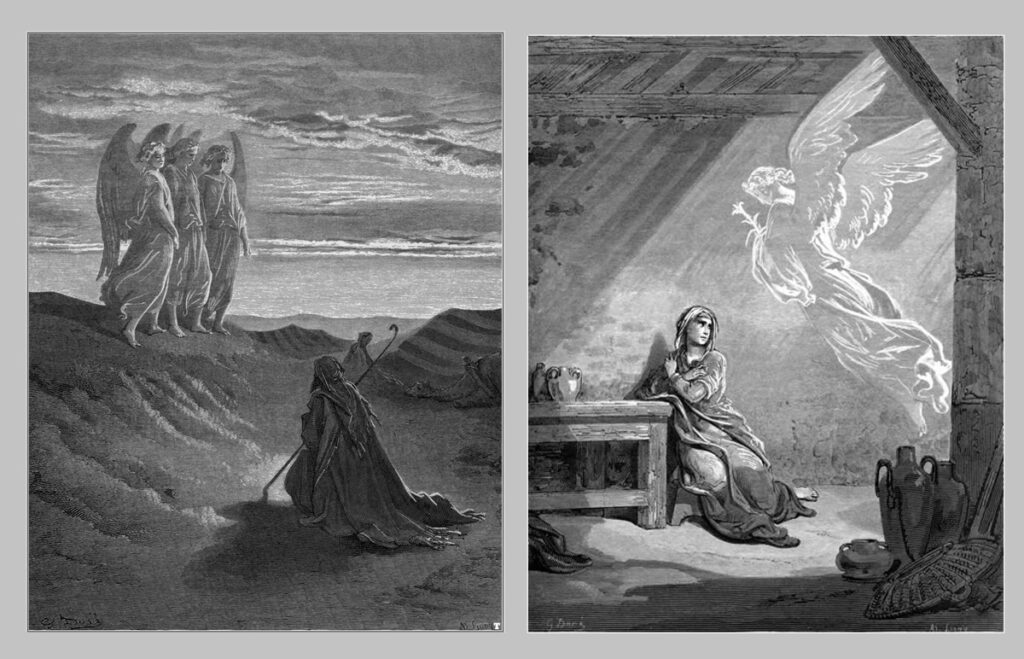

I looked for Dore’s depiction of old man Abraham meeting the three angels who tell him that his aged wife Sarah will have a baby in nine months. The image I found is both majestic and evocative.

More intimate is another scene in which another angel is arriving with baby news — the Archangel Gabriel coming to tell Mary that she will be the mother of God.

A clothed Susanna and a buff Jesus

One interesting aspect of Dore’s work is that he underplays the nudity that, over the previous three hundred years, often found its way into paintings of biblical events.

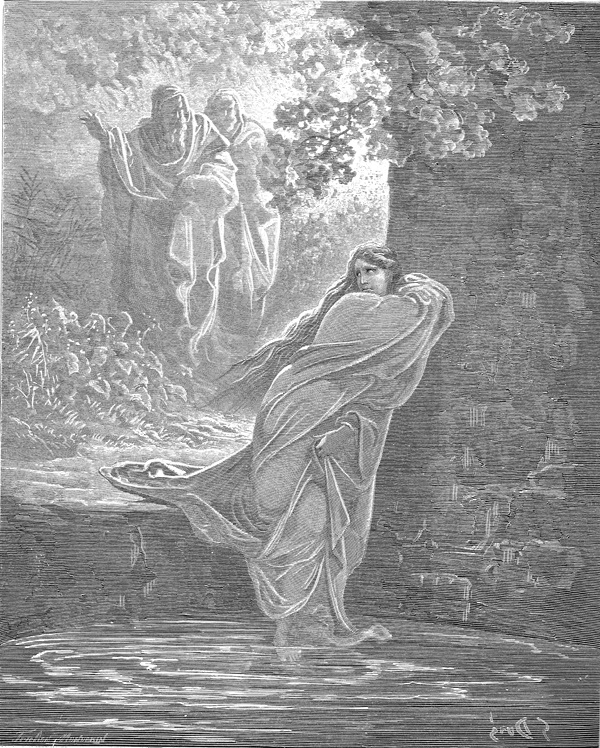

Such as the story of Susanna in the Book of Daniel. She is an attractive Hebrew wife who, while taking a bath in her private garden, is secretly ogled by two elders who accost her and try to blackmail her into having sex with them.

Often, the Susanna in this scene is shown fully nude, but that’s not what Dore does. Instead, he portrays the woman as soberly dressed, afraid and victimized by the two men.

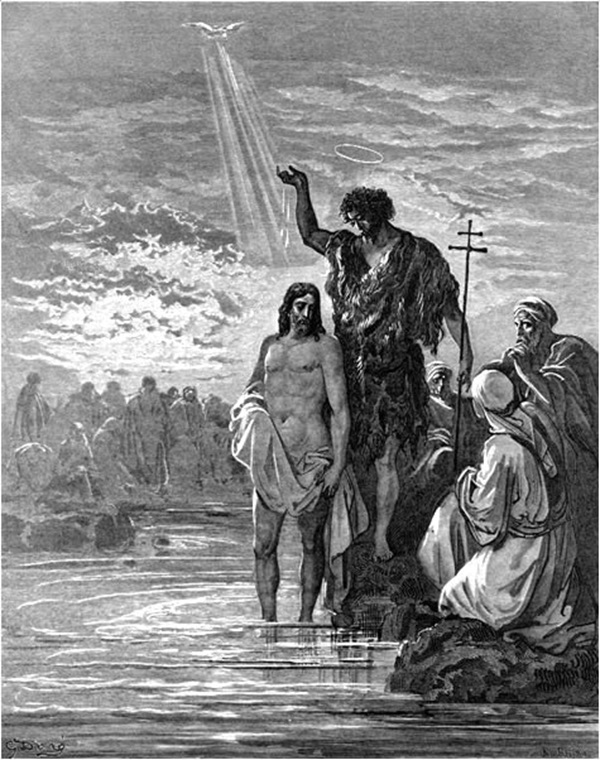

By contrast, Dore uses the Baptism of Jesus by John in the Jordan to present the reader with a nearly nude, surprisingly buff Messiah, not the usual depiction of this scriptural moment.

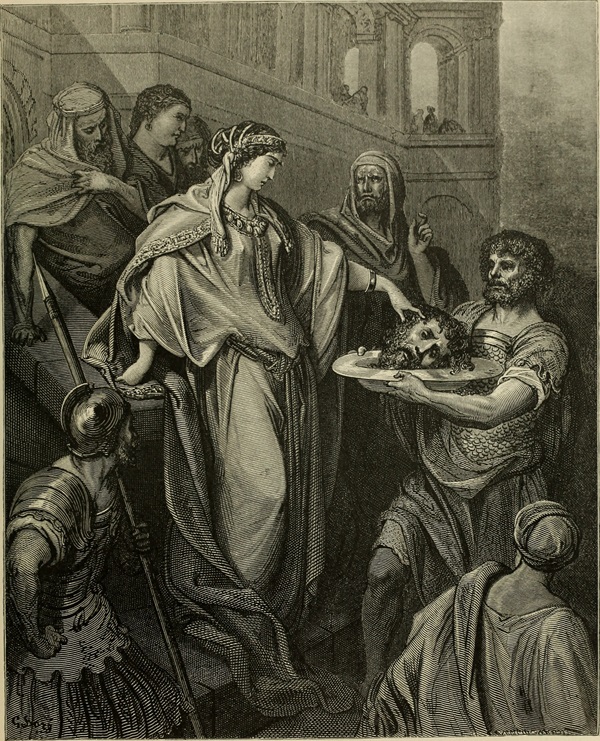

Severed heads

A lot of Dore’s images are pretty gruesome. For instance, there are a goodly number of severed heads in these 241 illustrations, such as the head of John the Baptist on a plate.

This is the gift that Salome, a Hebrew princess, demanded from her stepfather Herod Antipas after dancing for him at his birthday celebration.

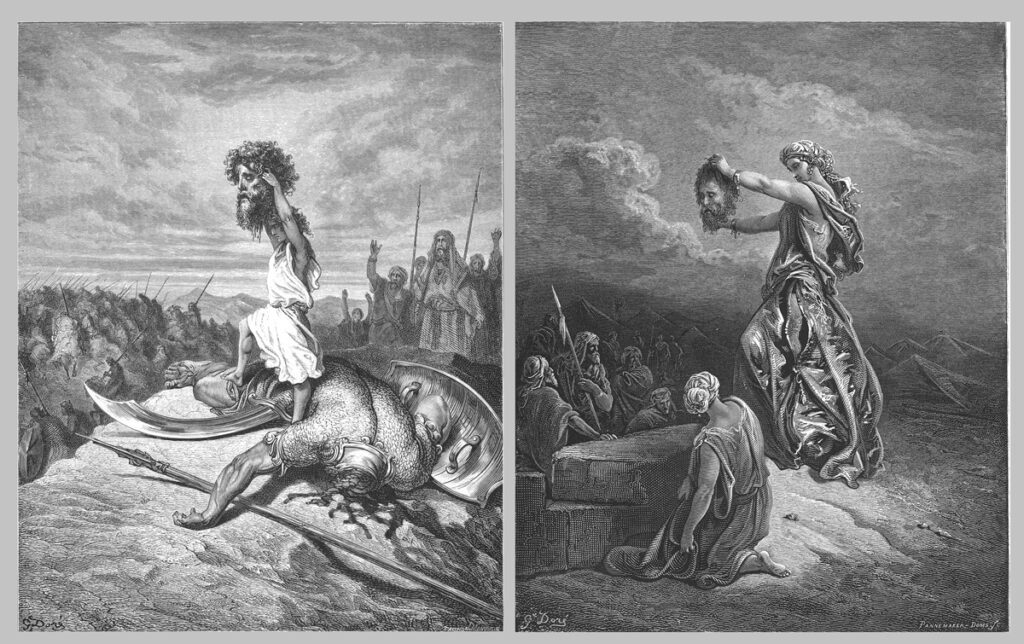

That’s a rather gross scene but not as gross as two others.

In one on the left, below, David is holding aloft the head of Goliath after killing him with a slingshot. The one on the right features the Hebrew widow Judith who saved her city by charming her way into the tent of the Assyrian general Holophernes and then hacking off his head. Here, she shows off her trophy.

One odd echo of these images comes from the 1994 animated movie Lion King. It occurs when the shaman Rafiki presents the newly born prince Simba to the pride. It’s not a scene of violence, but, well, there are those echoes.

Light and dark

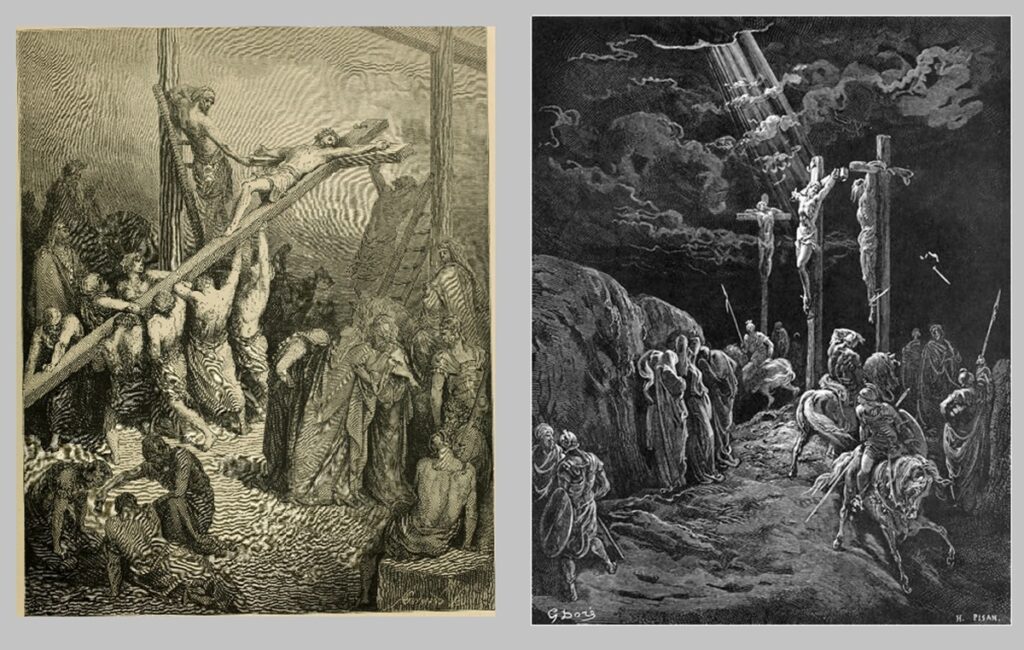

The culmination of Dore’s biblical illustrations is the crucifixion of Jesus, and it’s not surprising that he offers several versions.

One very affecting image shows the raising of the cross and the heavy labor involved as at least nine men strain to lift it and the isolation and vulnerability of Jesus, already nailed to the wood.

Another shows the three crosses — holding Jesus and the two thieves — highlighted by a ray of sunshine in what is otherwise a very dark moment. There is a cinematic quality to this that gives it quite a jolt.

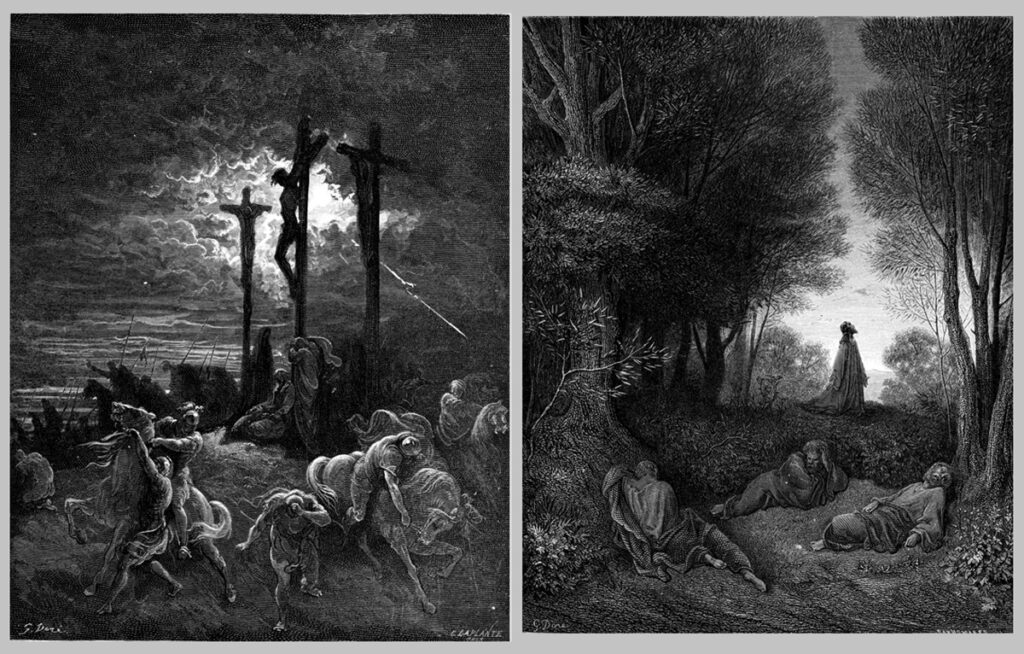

To my mind, though, much more poignant is Dore’s use of silhouettes to make a statement, such as the two scenes below: the crucifixion with the three crosses outlined against a spot of light in the dark sky and, earlier, Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane with his friends asleep nearby and his eyes looking up into the blank sky.

The Dore Bible Illustrations represent a rich trove of artful renderings of stories from the Book of Genesis to Revelations.

It is far from the final word for any other these stories. Yet, it is unquestionably a visceral response by the artist to the words of scripture — and one that is quite likely to evoke a visceral response from the viewer.

It is far from the final word for any other these stories. Yet, it is unquestionably a visceral response by the artist to the words of scripture — and one that is quite likely to evoke a visceral response from the viewer.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.13.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Looks like a cool book of biblical story illustrations. Wasn’t it Gabriel that appeared to Mary, not Michael? Maybe it’s different in the Dore version.

Yes, Gary, it was Michael! Thanks for catching that. I’ve fixed it now. Here’s where you can get the book if you’d like: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/048623004X/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1