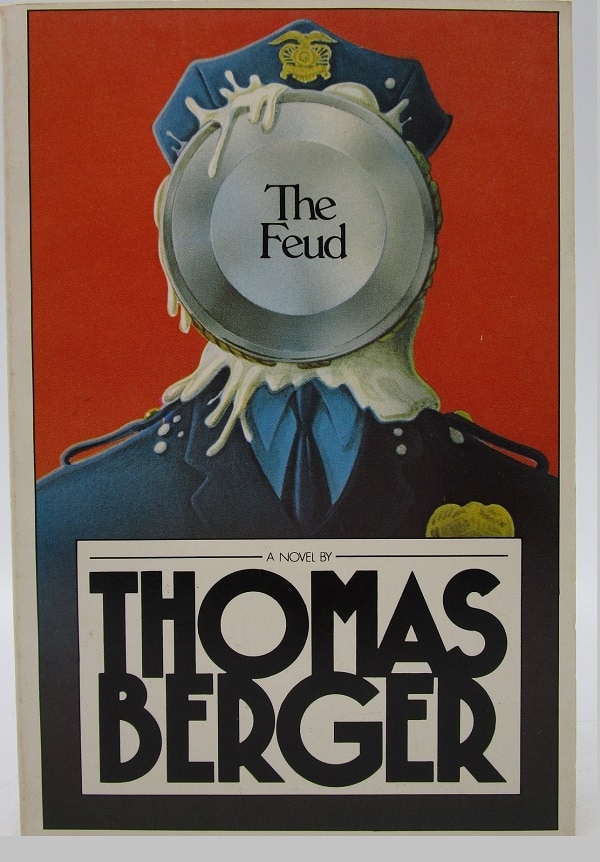

Thomas Berger’s 1983 novel The Feud is a screwball comedy which features two killings, a natural death after a fistfight, a botched suicide, a car bomb and a hardware store burned to the ground.

The Feud is an entertainment populated by a cast of goofy, pretty silly and generally amiable characters who don’t seem all that familiar with the idea of consequences. They act and — surprise! — things happen.

Comedy ensues.

And also those killings, the death, the mismanaged suicide, the explosion and the fire.

The characters in The Feud are pretty much all id.

And Berger sees them as if they were odd little insects that he has collected inside a glass case for the viewing pleasure of his friends. Just look at those crazy antics!

“Too fast to count”

One exception may be fifteen-year-old Jack Beeler who spends the novel trying to understand things. He’s always the odd man out.

His 17-year-old brother Tony — a star football linemen at the local high school, despite his glasses — is, like everyone else in the novel, a man of action rather than consideration. Such as when, driving Jack and their mother home, he knocks down and knocks out a police chief during a traffic stop for sassing off to his mom.

He hurled himself at the cop and gave him a series of punches too fast to count, but one or more of them knocked his enemy down, and out. The policeman lay prone on the asphalt.

Their mother called from the car. “Oh, my, Tony! You haven’t killed him, have ya?”

No. This isn’t one of the deaths in The Feud. The cop is only unconscious and, when he wakes up, embarrassed — as a lot of the novel’s characters find themselves at one or more points in this story.

Jack and Tony, who like but don’t much understand each other, are one of the many twosomes in this comedy of ineptitude.

Adolf, Jr.

Berger never says this straight out, but his story is set in small town America between the two World Wars.

A movie ticket, for instance, is fifteen cents. One character is thought to have been gassed in the war. Jack’s actual name is Adolf, Jr., and his father is Adolf, Sr., called Dolf. These names would have played a different role in Berger’s story if the action in the novel were taking place after 1940.

The twosome theme of The Feud starts on the novel’s opening page.

Dolf and his family live in Hornbeck, and, on that first page, Dolf — “a good husband and a nice man” — has gone to Millville, the next door town, to buy paint remover at Bud’s Hardware.

Dolf had come to Millville’s hardware store today because the one in Hornbeck was closed, owing to the recent suicide of its owner, George Wiedemeyer, for reasons as yet unexplained.

NOTE: This suicide, which is never again mentioned, much less explained, is not the attempted suicide somewhat later that plays a fairly important role in the novel’s plot. It’s probably worth noting that this is another example of twosomes in the book.

“Sobbed, and blubbered, and degraded himself”

While at Bud’s Hardware, the burly, middle-aged Dolf gets into a disagreement over his unlit cigar with Bud Bullard, the owner, and, then, he has his run-in with Bud’s cousin Reverton.

Reverton swept back the tail of his suit coat and pulled a revolver from a holster that hung there. “You sumbitch,” he said to Dolf. “You just back up against that there counter, you shit-heel bum. I know how to handle your kind.”

Dolf could not believe in the reality of this sequence of events. You went to buy paint remover and you had a gun pulled on you? He now tried to be reasonable.

But Reverton, a thin, small, nervous kind of guy, is having none of that and cocks his gun.

Dolf fell to his knees on the wooden floor, his hands crossed over his protuberant belly. But then he lifted them in supplication. He pleaded, “Oh, God, don’t kill me,” and sobbed, and blubbered, and degraded himself so thoroughly that later on he could not remember it without wanting to vomit.

Thus opens the feud.

Body count

It’s between the Bullards and the Beelers, and between the town of Millville and the town of Hornbeck, and it occurs in the midst of an ongoing feud between the police chiefs of the two town, both swaggering bullies.

And it complicates the life of Tony who is trying to court Eva who’s last name turns out to be Bullard (and who’s just 14…well, 13 when Tony meets her but, for her age, she’s well-developed).

There are echoes here of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and the dopiness of Berger’s characters has some parallels with the dopiness of the characters in some of the Bard’s comedies. And the body count at the end of The Feud is fairly Shakespearean.

Reverton and Bernice

Slicing through all the twosomes in The Feud are two un-twosomed characters.

There’s Reverton, one of life’s comically bitter losers, a small guy who carries a big gun — he tells everyone he needs it to fight off the hoboes in his job as a railroad detective — the sort of guy who never feels part of the life that’s going on around him and resents it and has no understanding of such things as social niceties.

The other is Bernice, the older sister of Tony and Jack, who has been living 15 miles away in the city but returns home to look for a guy to marry her and give his name to the unborn child she’s sure she’s carrying.

Although Bernice is not part of a twosome, she’s part of a series of twosomes as she is always ready for sex and not terribly discriminating.

Reverton and Bernice are fun any time they appear on Berger’s pages. And I’m wondering what might have happened if they had met and become a twosome, but, in the novel, they don’t.

Still, The Feud is a fun, pleasant entertainment in which tragedy and violence are overshadowed by dopiness.

At least, it is for those of us who are looking into the glass case from the outside.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.30.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.