Edna Ferber’s The Girls, a novel about three independent-minded South Side women yearning for vibrant lives, was originally published more than a century ago, but it’s written with such verve and insight that it could be a piece of historical fiction produced last week.

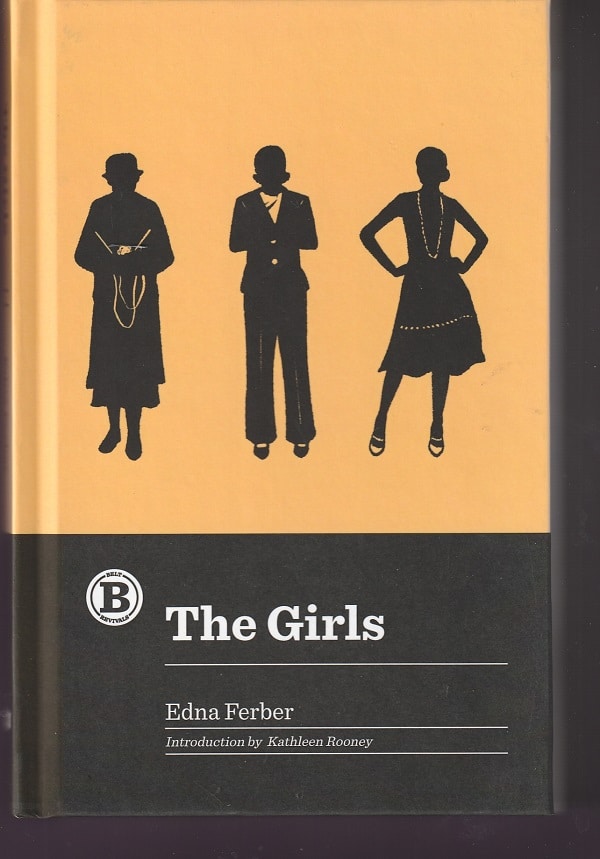

It’s available again in a new, handsome edition from Belt Publishing with an introduction by Chicago novelist, poet and publisher Kathleen Rooney and will captivate modern readers. Here’s hoping there are a lot of them.

Although often overlooked nowadays, Ferber could write, winning the Pulitzer Prize for her 1924 novel about a South Holland farm-owning woman So Big.

Her novel Show Boat was adapted as a Broadway musical by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II and as a movie three times while the film version of her novel Cimmaron won the 1931 Academy Award for Best Picture. Giant, based on her 1952 novel of the same name, starred Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean and was listed as one of the 100 best American movies by the American Film Studio.

Ferber spent most of her 20s and 30s living in Chicago with her sister and their widowed mother who bought and managed real estate. In The Girls, an important character is Carrie Payson, a sharp-edged mother of two sisters who gets into the real estate business after her husband absconds with virtually all of her father’s wealth.

The three Charlottes

Carrie is important, but not one of the “girls” of the novel’s title. They are three of those, and they are introduced by Ferber on the novel’s first page in an attention-getting opening in which the author directly addresses the reader and ponders how to start the story. She writes:

“It is a question of method. Whether to rush you up to the girls pell-mell, leaving you to become acquainted as best you can; or, with elaborate slyness, to slip you so casually into their family life that they will not even glance up when you enter the room or leave it; or to present the three of them in solemn order according to age, epoch, and story.”

Ferber opts initially for a short version of the third approach, presenting to you Great-Aunt Charlotte Thrift, “spinster, aged seventy-four”; her niece and namesake Charlotte “Lottie” Payson, Carrie’s daughter, “spinster, aged thirty-two”; and Lottie’s niece and namesake Charlotte “Charley” Kemp, “spinster, aged eighteen and a half.”

“Old maids!”

This is all in the first three sentences. And if you’re not laughing already at Ferber’s heavy-handed use of the s-word, she makes sure you’ll giggle when she goes on:

“If you are led by all this to exclaim, aghast, “A story about old maids!” — you are right. It is. Though, after all, perhaps one couldn’t call Great-Aunt Charlotte an old maid. When a woman has reached seventy-four, a virgin, there is about her something as sexless, as aloof and monumental, as there is about a cathedral or a sequoia.”

There are some men in the novel — Cassie and Charlotte’s father, the young man Charlotte swooned over as he was heading off to the Civil War, the Jewish fellow Lottie saw for a while, the kindly importer who married Lottie’s sister Belle and fathered Charley, the reporter-poet (not unlike Carl Sandburg) who hung out a long time with Charley before heading off the World War I, a former reporter in Paris with a sense of humor. And, of course, that obsequious Uriah Heep-like Samuel Payson who stole all that money and left the family in such a tizzy.

But, as the title indicates, The Girls is a novel about women — a wide variety of women, including a Women’s Court judge and a globe-trotting reporter and a young girl rescued from a life on the street and a group of unmarried well-to-do women who gather afternoons for gossip and lunching and two immigrant women who do kitchen and housework for two branches of the family and even a newborn baby.

How the clan circumscribes

Mainly, though, it is the story (stories) of Charlotte who wasn’t always 74 and Lottie who has made a personal faith of duty and Charley who has been floating through her young life.

For me, The Girls was reminiscent of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, published a year earlier in 1920, inasmuch as both novels have to do with how the clan — family and society — circumscribes the lives of its members.

In the Wharton book, Newland Archer, a member of New York City’s Four Hundred, is blocked from his efforts to break the constraints of his class to run away with the exotic Countess Ellen Olenska. In The Girls, the restraints are imposed within the family by parents and other relatives, exercising controls that either stifle the yearnings of young women or coddle them into inertia. At one point, Charlotte says to her niece:

“Lottie, you’re going to be eaten alive by two old cannibal women…Live [your life] the way you want to. Then you’ll have only yourself to blame. Don’t you let somebody live it for you. Don’t you.”

Charlotte knows of what she speaks from personal experience.

Resurrecting books

The Girls is one of an untold number of books from the past, long out of print, that should be available to hungry modern readers.

Unfortunately, the relative ease with which out-of-copyright books can be scanned and printed has resulted in a lot of shoddy work. What happens often is that the scanned book is digitized for an ebook, and, when the digital file is downloaded for a physical book, little or no thought is given to its formatting or copyediting. Many times, the printed book is virtually unreadable.

By contrast, New York Review Books, the publishing division of the New York Review of Books, has reprinted hundreds of great books from the past in well-produced, attractive, easy-to-read Classics editions. It’s the gold standard of giving out of print books a new lease on life.

The Ohio-based Belt Publishing has been doing its small part in this field. The Girls is the eleventh title in its very welcome Revival Series, bringing back into print and into public notice delightfully sparkling fiction and non-fiction jewels of the past.

Among the fiction titles already published are One of Ours by Willa Cather and Poor White by Sherwood Anderson. Non-fiction installments include such significant works as The Shame of the Cities by Lincoln Steffens, The History of the Standard Oil Company by Ida Tarbell and The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success against Great Odds by Marshall W. “Major” Taylor.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.25.23

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 3.20.23.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.