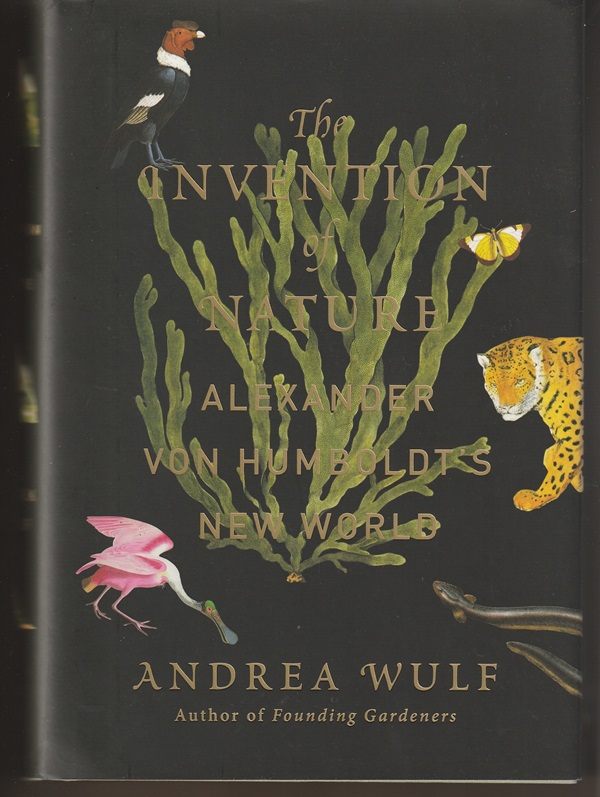

Historian Andrea Wulf packs a lot into 337 pages in her 2015 book The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt’s New World, and much of it will be surprising and enlightening to modern American readers.

During his long life, the German polymath Humboldt (1769-1859) was so famous as a naturalist-explorer and so influential as a thinker in so many areas of scientific inquiry that King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia called him “the greatest man since the Deluge.”

Hugely influential in his day, Humboldt’s ideas still permeate modern thinking, notes Wulf.

Humboldt revolutionized the way we see the natural world. He found connections everywhere. Nothing, not even the tiniest organism, was looked at on its own. “In this great chain of causes and effects,” Humboldt said, “no single fact can be considered in isolation.”

With this insight, he invented the web of life, the concept of nature as we know it today.

Indeed, Humboldt’s insights are at the heart of the recognition of present-day scientists and leaders of climate change and its impact on humans and the Earth.

When nature is perceived as a web, its vulnerability also becomes obvious. Everything hangs together. If one thread is pulled, the whole tapestry may unravel.

After he saw the devastating environmental effects of colonial plantations at Lake Valencia in Venezuela in 1800, Humboldt became the first scientist to talk about the harmful human-induced climate change.

Little-remembered

No wonder, then that the United States is awash with references to him:

- At least 14 states have a municipality or county called Humboldt.

- There is the Humboldt Peak in Colorado and another in Nevada, part of the Humboldt Range of mountains.

- At least seven U.S. cities and states have a Humboldt Park, including Chicago where the neighborhood to the west of the park has taken its name.

- In Nevada, there are five bodies of water named Humboldt.

- There are at least four Humboldt High Schools as well as Humboldt State University in California.

- There are two Humboldt Municipal Airports, in Iowa and Tennessee.

- And Humboldt Fleisher is the title character in Saul Bellow’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1975 novel Humboldt’s Gift.

Yet, few Americans and others in the English-speaking world remember him today.

“Last of the polymaths”

Part of the reason for this, writes Wulf, is the enormous breadth and depth of his scientific interests:

He was one of the last polymaths, and died at a time when scientific disciplines were hardening into tightly fenced and more specialized fields. Consequently his more holistic approach — a scientific method that included art, history, poetry and politics alongside hard data — has fallen out of favor.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, there was little room for a man whose knowledge had bridged a vast range of subjects. As scientists crawled into their narrow areas of expertise, dividing and further subdividing, they lost Humboldt’s interdisciplinary methods and his concept of nature.

A thinker and a German

In addition, Humboldt, for all his travels and explorations, was a thinker, and one who had much to say about many things. He wrote exciting and scientifically rigorous travelogues about his journeys in Latin America and Russia and a seemingly endless number of books about science and Nature and the impact of human beings on Nature.

Because of the breadth of his scholarship, his name is found on places and things across the world. But none of his ideas was singular enough to become a common phrase, the way that Morse Code is named for its co-inventor Samuel Morse or that the Doppler effect keeps alive the name of physicist Christian Doppler who first described the phenomenon.

And, then, as Wulf notes, Humbolt’s reputation was a victim of the anti-German sentiment that arose in the United States and Great Britain during and after World Wars I and II.

Both world wars of the twentieth century cast long shadows, and neither Britain nor America were places for the celebration of a great German mind any more.

Thinkers and visionaries

In The Invention of Nature, Wulf aims to reintroduce Humboldt to modern readers and restore his renown.

In The Invention of Nature, Wulf aims to reintroduce Humboldt to modern readers and restore his renown.

And, to do so, she uses her book to tell not only Humboldt’s story but also the stories of eight world-changers who were deeply influenced by him.

This is something of an authorial gamble inasmuch as Wulf weaves through her account of Humboldt’s life mini-biographies, some as long as 20 pages, of those other world-changers, four of whom never met him.

In fact, Wulf recounts Humboldt’s death on page 279 of The Invention of Nature, but this is followed by three chapters, more than 50 pages, about three of the pioneer thinkers who only knew the long-lived German by his writings.

The eight world-changers he influenced represent an amazing range of scientists and visionaries:

Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the greatest and most influential writer in the German language who was also a scientist and polymath, wrote his greatest work Faust a time when he and Humboldt were visiting each other regularly. Wulf writes:

Faust, like Humboldt, was driven by a relentless striving for knowledge, by a “feverish unrest,” as he declares in the play’s first scene. At the time when he was working on Faust, Goethe said about Humboldt: “I’ve never known anyone who combined such a deliberately channeled activity with such plurality of the mind” — words that might have described Faust.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson, the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, the third president of the United States and a polymath himself, feted Humboldt in 1804 in Washington, D.C., after the German’s explorations in Latin America.

Jefferson pummeled the explorer with questions about his discoveries and, even more, about the political situation in the nations he had visited.

Humbolt gave Jefferson nineteen tightly filled pages of extracts from his notes, sorted under headings, such as “table of statistics,” “population,” “agriculture, manufacturers, commerce,” “military” and so on. He also added two pages that focused on the border region with Mexico and in particular on the disputed area that so interested Jefferson.

Simon Bolivar

Simon Bolivar, the Venezuelan-born military officer who led wars for independence that resulted in the creation of the nations of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia, was an aimless 21-year-old when he met Humboldt in Paris later in 1804.

When Bolivar argued rapturously about the liberation of his people. Humboldt saw only a young man with a brilliant imagination — “a dreamer,” as he said, and a man who was too immature. Humboldt was not convinced, but as a mutual friend later recounted, it was Humboldt’s “great wisdom and accomplished prudence” that helped Bolivar at a time when he was still young and wild.

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin, the English naturalist whose books and theories on evolution, particularly The Origin of the Species, made him one of the most influential people in human history, met the verbose Humboldt in England in 1842 but couldn’t get a word in edgewise.

Yet, Humboldt’s books had already become — and would continue to be — a major inspiration in his career.

During his voyage on the HMS Beagle at the start of his career, he wrote his brother to look at Humboldt’s Personal Narrative to get an idea of what he was going through, and told his father, “If you really want to have a notion of tropical countries study Humboldt.”

Darwin was seeing this new world through the lens of Humboldt’s writing…Throughout the Beagle’s voyage, Darwin was engaged in an inner dialogue with Humboldt — pencil in hand, highlighting sections in Personal Narrative.

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau, an American naturalist, essayist, poet and philosopher, is the first of the four great thinkers who were profoundly inspired by Humboldt’s writings but never met the man.

While writing his masterpiece Walden, Thoreau was reading and re-reading Humboldt’s books, particularly Cosmos, filling his notes, journals and published works with such phrases as “Humboldt says” and “Humboldt has written.”

Thoreau began, as he said, to “look at Nature with new eyes” — eyes that Humboldt had given him. He explored, collected, measured and connected just as Humboldt did.

His methods and observations, Thoreau told the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1853, were based on his admiration for Views of Nature, the book in which Humboldt had combined elegant prose and vivid description with scientific analysis.

George Perkins Marsh

George Perkins Marsh, an American diplomat and philologist, who is seen by some as the nation’s first environmentalist and by others as an early conservationist. His book Man and Nature, published in 1864, took “Humboldt’s early warning about deforestation to its full conclusion,” telling “a story of destruction and avarice, of extinction and exploitation, as well as of depleted soil and torrential floods.”

Humboldt had taught Marsh about the connections between humankind and the environment. And in Man and Nature Marsh reeled off one example after another of how humans interfered with nature’s rhythms.

Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Haeckel, a German zoologist, naturalist, marine biologist and artist, who discovered and named thousands of new species and coined the term “ecology,” was a young man in 1859 when he heard of Humboldt’s death and was forced to face a personal dilemma.

The news that Humboldt was dead — the man whose books had inspired Haeckel’s love for nature, science, explorations and painting since early childhood — triggered that crisis.

He was in Naples gathering information for a scientific paper but all he wanted to do was to throw himself into the heart and beauty of Nature.

In one letter, Haeckel filtered his doubts through the lens of Humboldt’s vision of nature. How was he to reconcile taking the detailed observations that his scientific work required with his urge to “understand nature as a whole?”

He chose to follow in Humboldt’s footsteps and throw himself into encountering and interacting with nature and became “one of the most controversial and remarkable scientists of his time — a man who influenced artists and scientists alike, and one who moved Humboldt’s concept of nature into the twentieth century.”

John Muir

John Muir, a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist, and early advocate for the preservation of wilderness in the United States, said, in his late 20s, “How intensely I desire to be a Humboldt,” desperately yearning to see the “snow-capped Andes & the flowers of the Equator.”

It would be more than four decades before Muir would be able to fulfill that dream, but, in the meantime, he because a Humboldt of the American West, writing about the natural beauty of the Rocky Mountains and advocating for national parks and preservation of the American wilderness.

In the decade after his first summer in Yosemite, Muir turned to writing to “entice people to look at Nature’s loveliness.” As he composed his first articles, he studied Humboldt’s books as well as Marsh’s Man and Nature and Thoreau’s The Maine Woods and Walden….

Humboldt’s ideas had come full circle. Not only had Humboldt influenced some of the most important thinkers, scientists and artists but they in turn inspired each other. Together, Humboldt, Marsh and Thoreau provided the intellectual framework through which Muir saw the changing world around him.

Inventing nature

In a way, one could argue, after reading Wulf’s book, that the title undersells the book.

Yes, it’s legitimate to call this biography The Invention of Nature, but, as Wulf herself shows in extensive detail, it might just as well have been called The Invention of Nature by Alexander Von Humboldt and His Many Followers.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.29.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.