It takes some hubris to rewrite the Christian gospels, but maybe not that much. A lot of people have done it.

The gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John seem pretty straight-forward inasmuch as they’re telling stories that the authors assert are true. A few facts, some action, some words.

For many sophisticated and educated people of the last two centuries, these stories were fine as far as they went, except for the stuff that, well, just didn’t make sense. Such as the miracles, including the resurrection. And those teachings that, clearly, were so wrong-headed.

The temptation for a great writer to run the gospels through the typewriter to smooth out the rough edges and add a little polish and shape the narrative must be very strong. Norman Mailer, for instance, did it with The Gospel According to the Son (1997), and Charles Dickens with The Life of Our Lord (1849). And so did Leo Tolstoy.

In 1893, Tolstoy put together The Gospel in Brief which, he writes, “effected the fusion of the four Gospels into one, according to the real sense of the teachings.” He did a kind of cut and paste, slicing out all of the verses of the four gospels and then putting them in the order he thought they should follow.

The result, he wrote, was that this was the “real sense” of Jesus’s message, not what had been pedaled by Christian clerics for 19 centuries.

Tolstoy also wrote that it was “the Gospel according to the four Evangelists … presented in full.” But it wasn’t. He added this long sentence of explanation:

But in the rendering now given, all passages are omitted which treat of the following matters, namely, — John the Baptist’s conception and birth, his imprisonment and death; Christ’s birth, and his genealogy; his mother’s flight with him into Egypt; his miracles at Cana and Capernaum; the casting out of devils; the walking on the sea; the cursing of the fig-tree; the healing of sick, and the raising of dead people; the resurrection of Christ himself; and finally, the reference to prophecies fulfilled in his life.

“The Life and Morals”

More than seven decades earlier, in the first months of 1820, another world-famous figure undertook the same task of creating a better version of the gospels — a highly acclaimed writer who was also a successful revolutionary and the third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson.

Unlike Tolstoy, Jefferson created The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, now popularly known as the Jefferson Bible, for himself alone, not for the public. He’d already had enough guff about his religious beliefs, or lack thereof, throughout his long career in the limelight of history to mention it publicly and spark more controversy. Even so, he didn’t shy away from describing in letters to friends his plan to carry out this revision or his accomplishment of it.

He finished the task at the age of 77 and reportedly read from The Life and Morals every night until his death six years later.

“A great religious book?”

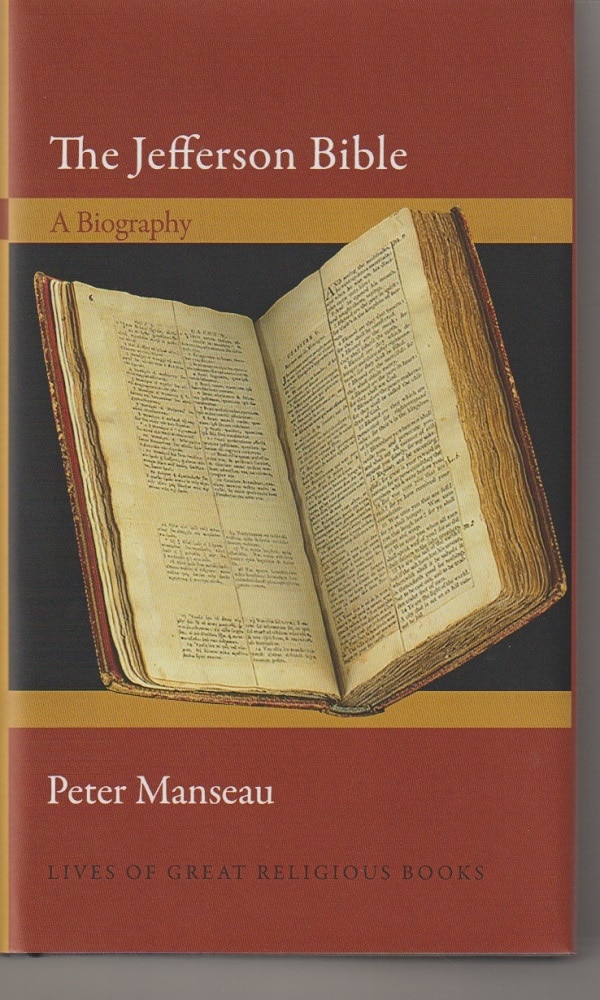

Peter Manseau’s The Jefferson Bible: A Biography is a meaty, nuanced and lively look at The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.

It is a new installment in the stellar and sprightly series Lives of Great Religious Books from Princeton University Press. An eminently erudite and spirited group of more than two dozen “biographies” of such works as Genesis, the Koran in English, The Book of Common Prayer, the Talmud and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Each entry in the series, written with verve and style by an expert, is about 200 pages, and it tells how the particular religious work came into being, what it says and how it has impacted world culture since its creation. Each book is strong in clarity and pithy quotations and historical perspective.

All of this is true for Manseau’s book. Nonetheless, he rightly asks early on in his introduction:

But is [the Jefferson Bible] a great religious book?

“Any suggestion”

It’s a legitimate query since the public never knew of Jefferson’s privately created and privately employed work until the early years of the 20th century. It wasn’t created for a community of believers. Given Jefferson’s Deistic beliefs, it would be correct to say it wasn’t created for a religious purpose at all. Jefferson kept in his version those parts of the gospels that had to do with morals and right living.

In fact, like Tolstoy, Jefferson listed in a letter to a friend the sort of things he was going to excise from the accounts:

The immaculate conception of Jesus, his deification, the creation of the world by him, his miraculous powers, his resurrection and visible ascension, his corporeal presence in the Eucharist, the Trinity, original sin, atonement, regeneration, election, orders of hierarchy, etc.

The inclusion of “the immaculate conception” in reference to Jesus, Manseau writes, was an indication of Jefferson’s amateur status when it came to religion and the Bible. The term has been traditionally applied to his mother Mary.

Jefferson’s point, though, was that “any suggestion that there should be some mystical origin to a poor first-century preacher much of the world had come to call God simply did not make the grade.”

So Jefferson, politician that he was, begins his book with taxation:

AND it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.

“Dramatically different interpretations”

So, it can be argued, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth isn’t a religious book.

Yet, Manseau points out that, in fact, this creation is many books at once. Yes, it’s the physical manuscript that Jefferson glued together and is now housed at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

So, too, it is the many different editions of Jefferson’s redaction, which cumulatively have sold hundreds of thousands of copies since its first publication more than a century ago.

Each later edition might be seen as a book distinct from the others, and each draws selectively upon the larger corpus of Jeffersonian thought, quoting his piquant correspondence related to the project in order to frame Jefferson’s gospel with epistles and apocrypha supportive of dramatically different interpretations of the primary text.

The physical object that Jefferson created two centuries ago remains as he created it. But, since its initial publication 116 years ago, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth has been constantly reborn as a religious work in new and quite amazing ways:

The Jefferson Bible has been given new meanings with each generation, new arguments and understandings of what Jefferson did and why…As with other culturally important sacred tomes, the greatness of the Jefferson Bible can perhaps be found less in the text itself than in what it signified.

It is less a book to be read than to be talked about. In fact, as much of the published commentary about the Jefferson Bible suggests, some have talked at great length about it without apparently having read it at all.

“A maker, a builder, a social engineer”

For example, one of the first people to publish the book within an idiosyncratic framework was the Rev. Dr. Henry Jackson, a Presbyterian minister whose mid-life new career was in social engineering. This is a school of thought that believes that, with the right amount of mechanic-like tinkering, human society, like a machine, could be adjusted to work better and more efficiently.

When it came to the Jefferson Bible, Jackson tinkered with the former President’s text, adding some New Testament scenes that had been left out. More important, though, was Jackson’s conclusion that the work was a roadmap of social engineering:

Out of the one hundred sections of His teaching in the Jefferson Bible as many as fourteen are devoted to the practical question of money. He treated this disturbing question more than any other, and to a surprising extent…

Contrary to common opinion, Jesus was eminently practical. He was a poet, a maker, a builder, a social engineer. Our sole aim here is to discover whether Jesus offered a big constructive principle effective for the creation of a better society.

Sure enough, Jackson found that “big constructive principle.” It was choosing a life with

“the attitude of duty, freely chosen without reservations of any kind….To discover this ideal and maintain it against all opposition, He believed, is the commanding duty and satisfying joy for every man.”

“The gospel about and of Jesus”

Often, over the past century, devout Christians have sought to claim Jefferson and his self-made Bible as more devout than they would appear. This has been particularly true in recent decades when efforts by some conservative Evangelicals have wrestled and tortured Jefferson’s verse choices for his Life and Morals into a document of fundamentalist Christian faith.

Such attempts would. I suspect, scandalize Jefferson.

More likely to garner his approval was the publication in 1964 of a new edition of Life and Morals with a long, passionate introduction by the Unitarian minister Rev. Donald Harrington of New York City’s Community Church, a multicultural, interracial congregation. Manseau writes:

Unlike the 1961 edition or those published a generation before, Harrington foregrounded not Jefferson’s conventional religious upbringing and attachment to the Bible, but rather his deep ambivalence about being part of a religious tradition whose moral teachings he treasured but whose dogmas he could not fully embrace.

Harrington acknowledged that Jefferson held “unorthodox views about Jesus” throughout his life, and he wrote:

It has been said that there are two contradictory religions side by side in the standard New Testament — the gospel about Jesus and the gospel of Jesus. Jefferson was not interested in the gospel about Jesus, which he found false, misleading and impossible for an educated man to believe. He was passionately devoted to the gospel of Jesus, which stirred him to the depths of his being and was the most powerful motive force in his life.

“Perfect reliquary”

Jefferson’s position as a key Founding Father of the United States guarantees that his Bible will continue to be looked at and evaluated from political, cultural and religious perspectives for as long as this nation continues. (It would be worth knowing if there is much or any interest in Life and Morals anywhere else on the globe. I don’t think Manseau mentioned this at all.)

At the end of his book Manseau write about three hairs, presumably Jefferson’s, found in the glue during a restoration of his manuscript and what the DNA in those hairs might have to show in the future about his family relationships. And, seeking to put the Jefferson Bible into context, Manseau concludes:

Conceived as a corrective to irrational religiosity and embarrassing superstitions, the Jefferson Bible has somehow become the perfect reliquary. The book turns out to be a repository not just of Jefferson’s beliefs — that religion and reason could be reconciled, that even for a heretic and a revolutionary, the stubborn influence of tradition perdures — but also of his body…

Since its rediscovery, every generation of Americans has turned to it to learn what they might about the man who made it, using every new tool at hand. With Jefferson as guide, we continue to dig.

.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.10.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.