In the summer of 1874, Edouard Manet visited the home of Claude Monet in the Paris suburb of Argenteuil, and, as Ross King recounts,

he began painting The Monet Family in their Garden at Argenteuil [portraying] Camille and Jean, then seven years old, seated on the grass amid the sprawl of her white dress; nearby a blue-smocked Monet stooped over one of the borders in his beloved garden, a watering can at his feet.

At some point, Monet stopped gardening and began painting his visitor in a canvas later titled Manet Painting in Monet’s Garden in Argenteuil.

And, even as he started, Monet received another visitor, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who, seeing what the others were up to, borrowed paints and a canvas and started Madame Monet and Her Son.

Manet’s painting is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Monet’s painting is in a private collection.

Renoir’s work is at the National Gallery in Washington.

Delightful story

It is a delightful story that captures much about the Impressionists — their spontaneity, their delight in painting in plein air, their desire to depict modern life in all its mundaneness and their friendship as comrades creating a new kind of art.

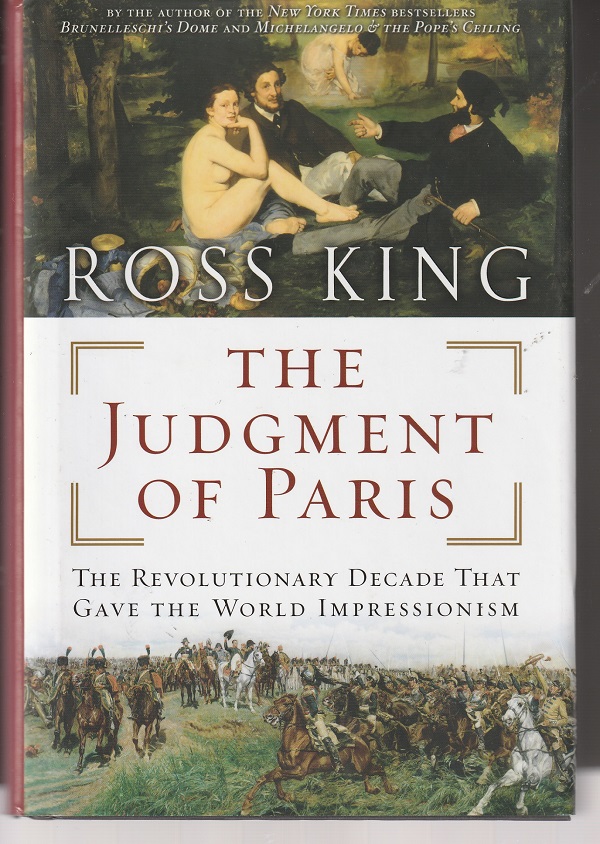

By no means, however, were they walking lockstep with each other, as King details in his 2006 book The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism.

For one thing, Manet wasn’t really an Impressionist. Eight years older than Monet and seven years older than Renoir, Manet had been, for the last decade, the leader of the artistic counterculture known as Realism.

Unlike most of the painters who came to make up the Impressionism movement, he was not averse to painting religious and political subjects, and he was hungrier than his younger friends for the approval of the artistic establishment, even though he was most often greeted with jeers and japes. He avoided painting outdoors until the end of his career. And, at least early on, he found much not to like in the work of the younger artists, even going so far as to try to avoid meeting Monet.

Yet, by 1874, Manet and the others had grown comfortable as artistic comrades, and, after years of being on the outside looking in, they were finally winning critical and financial success.

The tables of history and taste had turned, and their revolution of artistic vision was finally starting to triumph.

Artistic revolution

Artistic revolution

King’s The Judgment of Paris recounts how that artistic revolution took place in the French capital, during a time of political repression and unrest, of war and socialist revolt.

Starting in 1863, King builds his narrative around the annual Salons that the government sponsored. For the most part, these exhibitions were tightly controlled by conservative artists for whom history painting and the painting of stories and the painting of moral lessons were the height of achievement. Highly refined, highly finished canvasses, often bloody and/or eroticized, were the epitome of success for them.

They looked down their noses at the efforts of Manet and the rest to use everyday life as the subject of art.

King’s story is also built around two important artists: Manet, “the widely acknowledged leader of this new generation,” and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, “the world’s wealthiest and most celebrated painter.”

“The life of bygone days”

As the book opens in January, 1863, Meissonier is on the balcony of his mansion, dressed in the uniform of Napoleon Bonaparte — not a replica, but the thing itself — and, seated on a wooden horse, is looking at himself in a mirror and painting on a wood panel a study for one of his masterpieces, 1814: The Campaign of France.

Like the French art establishment, an arm of the national government, Meissonier was a painter of the past and a believer in the idea that the aim of art was to provide moral uplift — or, at least, entertainment rooted in a hazy nostalgia. He had made his name and his great wealth creating small, exquisitely detailed and perfectly rendered works, bursting with evidence of his legendary virtuosity.

He specialized in scenes from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century life, portraying an ever-growing cast of silk-coated and lace-cuffed gentlemen — what he called his bonshommes, or “goodfellows” — playing chess, smoking pipes, reading books, sitting before easels or double basses, or posing in the uniforms of musketeers or halberdiers….

This sense of nostalgia predisposed the French public toward Meissonier’s paintings, which were celebrated by the country’s greatest art critic, Theophile Gautier, as “a complete resurrection of the life of bygone days.”

At this point in his life as a painter, Meissonier was looking beyond such small scenes of “goodfellows,” no matter how lucrative they had been, and aiming to achieve greater status in his art world by attempting much more lofty subjects, such as Napoleon.

“A smeary lack of fine detail”

Manet, meanwhile, was just trying to get noticed. Unfortunately, what notice he found was almost always negative.

For instance, when he mounted a one-man show in 1863, visitors threatened his works with violence.

Most offensive to their sensibilities was Music in the Tuileries, a chaotic-looking blaze of figures painted with a smeary lack of fine detail….

The viewing public was accustomed to standing close to paintings, studying them minutely and marveling over the delicacy of the handiwork. The work of a master like Meissonier even repaid, as John Ruskin would discover, the scrutiny of a magnifying glass.

But Manet’s apparently clumsy brushstrokes and lack of clarity in Music in the Tuileries did not lend themselves to this sort of appreciation. The work looked lackadaisical and incomplete because in places the undercoat of white primer and the weave of the canvas could clearly be seen.

Another example of this was how Manet differed from Meissonier in the handling of horses. Meissonier was considered a genius as a painter of equine anatomy, particularly in motion. By contrast, Manet’s Races at Longchamp (1864) depicted horses with a radically different eye.

Manet was not interested in recording for posterity the duel between [the two favored horses], or even showing what the individual horses looked like. They were mere dabs of paint in the background — a few flying forelegs and a cloud of dust rather than the elegant, lifelike beasts at which Meissonier excelled.

A different nation

King’s book focuses on the eleven years from 1863 to 1874 — The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, as the subtitle has it. It was a period in which the new artists who became the Impressionists slowly began to find success while the traditionalists started to fade from fashion.

This changing of the guard in the art world mirrored and was affected by changes in the nation that resulted when an ill-conceived war with Prussia led to the capture of Emperor Napoleon III, the last monarch of France.

In quick succession, the Third Republic was established to replace the monarchy, the Prussians laid siege to Paris for more than four grueling months of starvation and deprivation, and, later, for a two-month period in 1871, the revolutionary Paris Commune seized power in the city before being brutally and violently crushed by the National Guard.

By 1874, France was a much different nation than it had been in 1863. And that couldn’t help but have an impact on its art.

For one thing, the old nostalgia for the past had been blown sky high. The military failures of this period meant that French people weren’t interested in being reminded about Napoleon. And this had a direct impact on Meissonier who spent, literally, a decade painting a work about Napoleon, only to have it fall flat when it was finally unveiled.

“Rival ways of seeing the world”

To his credit, King creates fully rounded portraits of Manet and Meissonier in The Judgment of Paris. In the wrong hands, Meissonier could have been turned into a conservative buffoon — as art criticism has characterized him over the past century and more.

Instead, King shows that Meissonier, for all his pomposity and wealth, was a painter striving to challenge himself with new subjects and new techniques, a worthy artist who, to his misfortune, found himself overwhelmed by a seismic shattering of all he had understood art to be. As King writes:

The difference between Meissonier and Manet was actually over artistic aims and techniques…. This struggle concerned rival ways of painting as well as, ultimately, rival ways of seeing the world, and it would result in the greatest revolution in the visual arts since the Italian Renaissance….

More than a century after their deaths, Manel “endures in glory, flooded with light and fame,” while Meissonier gathers dust in museum storerooms.”

King does right by Meissonier and Manet. He is masterly in weaving together the complex events and clash of ideas of this eleven-year period.

And he remains always aware that one element of art is fashion. After the triumph of the Impressionists, the work of Meissonier and his generation of painters suddenly became old hat.

Yet, just as Western culture changed to make it possible for the Impressionists to find their audience at the end of the nineteenth century, it can change again.

And who knows? Sometime, in the future, the work of Meissonier may be rediscovered. King’s book makes it clear: Meissonier was no buffoon. He was an artist. And that says much.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.2.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.