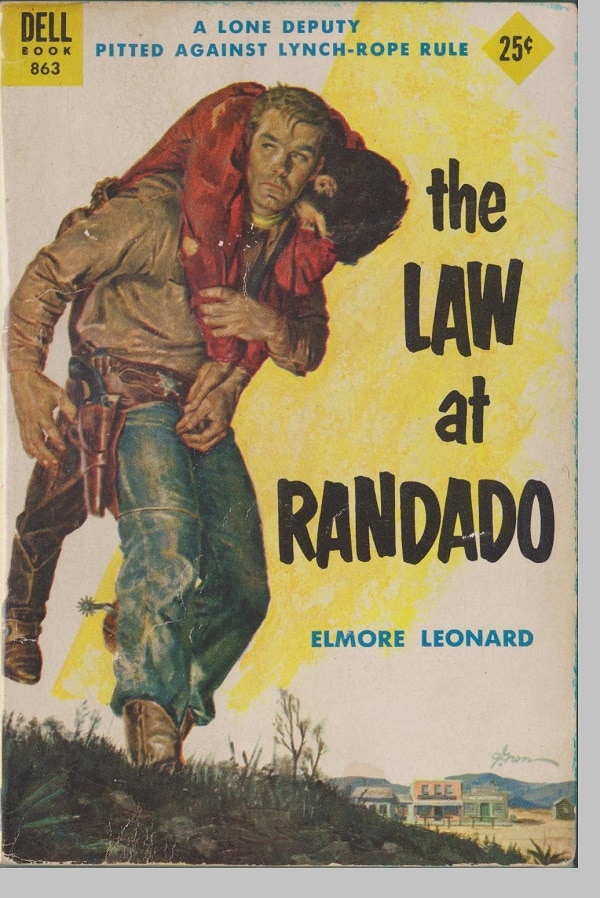

The 29-year-old Elmore Leonard had been a professional writer for just three years when, in 1954, he published his second novel The Law at Randado. It’s a book that displays some of the awkwardness one would expect from a new writer.

But what struck me most in a recent reading of the book was how assured Leonard was, even at this early time, and how committed he was to his own story-telling vision.

A central character in Randado is the rich young bully named Phil Sundeen. Fifteen years after the appearance of this book, Sundeen pops up again in Gunsights, a novel with all the hallmarks of the fully mature Leonard — snappy dialogue, quirky characters, good guys who are pretty good but not saints, sudden violence by sociopaths and a refusal to stay on the clichéd genre path.

Although Randado doesn’t fully measure up to Gunsights, it’s an abundantly entertaining novel, still fresh and vibrant nearly seven decades after it was written.

Shot glass

Consider the western cliché of the shootout.

Sundeen hires a gunslinger named Clay Jordan, a cold, amoral technician of murder. As soon as Jordan appears on the page, the reader of western novels knows that Kirby Frye, the book’s hero, is going to have to face him down on the town’s Main Street in a duel.

Except that’s not what happens.

Except that’s not what happens.

There is a battle between the two, but without all the High Noon romance.

Similarly, Sundeen sets up a situation in the town’s saloon that can only result in a gunfight with Kirby that he, with his cheating ways, expects to win.

Except that’s not what happens.

Kirby and Sundeen do face each other in this way, but the engagement is won with a shot glass.

“Day-old taste”

Leonard’s novels have always been remarkable for his easy incorporation of racial and ethnic minorities in his plots (even as his characters of all stripes used the full range of politically impolite words).

And these aren’t stick-figure stereotypes, but wackily idiosyncratic human beings who, in Leonard’s sentences and paragraphs, express feelings and thoughts that any other human being can relate to. This is true even when the minority member or, for that matter, the white character is a criminal or someone with what might be daintily described as an anti-social personality.

This was already happening in Randado which opens with Dandy Jim, a Coyotero Apache, looking out the window of the jail cell. The night before, Kirby, a former Army colleague, had locked him up for being drunk and having something to do with a still for making tulapai, a liquor.

The Coyotero sat up and ate the food: meat and bread. There was coffee, too, and after this he felt better. The throbbing in his head was a dull pain now and less often would it shoot through his eyes. The food removed the sour, day-old taste of tulapai from his mouth and this he was more thankful for than the full feeling in his stomach.

Dandy Jim is a fairly minor character in Randado. For Leonard, though, it’s important for the reader to have a feel for him as well as just about everyone else.

“Different in daylight”

Even Sundeen.

Late in the novel, the bully is being sought by Kirby and a posse, and he sneaks into an apartment above a store. This is the home of a married woman who, whenever her husband was out, would open her door and her bed to Sundeen for some quick night-time sex.

He helps himself to a bottle of whiskey and rolls himself a cigarette.

He felt pretty good now even though his legs were stiff and he had a kink in his back from all that riding. He felt good enough to grin as he thought: Damn room looks different in the daylight.

Sundeen may be a dominating brute. He may lack restraint, and he even may deserve to be called evil.

But, for Leonard, he’s still a human being, and getting inside his head, I suspect, was fun for the writer. It’s fun for his readers.

“Running neck-straining”

Even a lynch mob.

In this early novel, Leonard includes one of the most intense scenes in his entire body of work — the lynching of two Mexican cow thieves at the instigation of Sundeen and his stooges.

Of the book’s 301 pages, the writer devotes 23 to these scene from when the mob breaks into the jail, hauls the men to the livery stable, stumbles about trying to find rope and figure out the logistics of the thing, and then do the deed.

It is a horrible scene of power gone wild and mob psychology.

Then suddenly voices again, a cheering from the people in the street as the men, dragging the two Mexicans, seemed to burst from the front door of the jail into the sunlight.

And now the excitement, the not wanting to miss anything, the not wanting to be left out, was in the street. It was there suddenly with the noise and the stark violence of what was taking place. People joining the crowd, running neck-straining, behind the ones closer to the Mexicans…

Even the members of a lynch mob are, for Leonard, human beings.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.21.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.