A little more than a year from now, the 2024 Democratic National Convention will be held in Chicago, marking the 27th time that the city has played host to one or both of the major parties. Two of the Democratic gatherings were especially history-making: the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and the chaos of anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and police violence in the streets of the city during the 1968 meeting.

Arguably, the most significant presidential convention was the first ever held in the city — the Republican meeting in 1860 that, against all expectations, named Abraham Lincoln as the party’s standard-bearer.

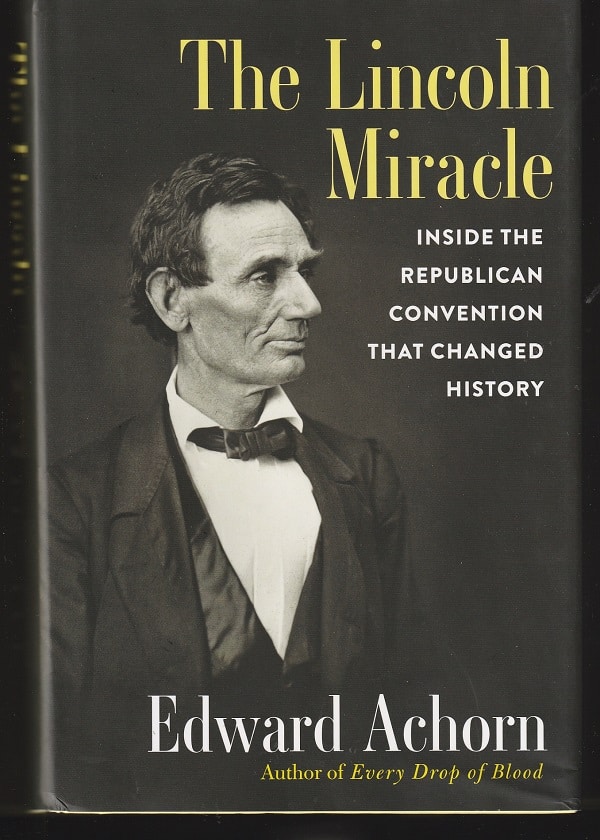

Historian Edward Achorn calls his book about that convention The Lincoln Miracle, and the nomination of the relatively obscure Springfield lawyer did seem to be that shocking, as if the result of supernatural hocus pocus. It was, however, as Achorn details, brought about by a wide array of very down-to-earth factors, above all, the hard work and savvy politicking of Lincoln’s tiny band of friends and allies at the convention, led by Circuit Court Judge David Davis of Bloomington.

They faced a daunting task.

The nomination appeared to be in the bag for U.S. Sen. William H. Seward, a former New York governor and one of the most prominent figures in the six-year-old anti-slavery party. In the months leading up to the gathering, everyone expected that he’d win — particularly Seward himself and his top political ally Thurlow Weed, one of the nation’s first political bosses. They certainly felt they’d done enough work to line up the votes for him, ensuring him a wide lead at the opening of the convention.

Nonetheless, the frontrunner was controversial — and vulnerable — for stating that there was “an irrepressible conflict” between those for and against slavery and for suggesting that there was “a higher law than the Constitution” when it came to a moral issue such as slavery. Luckily for him, the rest of the candidate field was fragmented among as many as a dozen favorite sons and presidential wannabes.

The only hope to stop Seward was for the opposition to join together behind one of the other candidates, and that’s what Davis set out to do. Yet, even as he and his allies were lobbying the delegations from other states, they were also putting to use their hometown advantage as convention hosts.

The Seating Plan

Six months earlier, Lincoln friend Norman B. Judd had traveled to New York to pitch Chicago as the meeting site to Weed and other party leaders who, Achorn writes, ended up choosing it “because they believed no serious threat to Seward would emanate from Illinois.”

Judd also finagled the job of determining the seating chart for the convention, and, late one night, shortly before the politicians began arriving in the city, he sat down to draw it up. As he was finishing up, his wife came over and, according to their son’s later recollections, took a look at the chart and said, “By cracky, Abe’s nominated.”

What Judd had done was to assign New York and all of the other states that were solid for Seward to the right of the podium. To the left, in their own section, were Illinois and all of the delegations that didn’t like or were lukewarm about the frontrunner. In between was the center section of reporters, effectively blocking the New Yorkers from button-holing wavering delegate during the convention sessions.

There was other skullduggery, such as packing the galleries with loud-voiced crowds of Lincoln supporters. And there were political trades, such as offers of cabinet posts made by Davis and his circle — even though Lincoln told them not to make such deals. (He never refuted the deals they did make.) And there were the calculations that politicians had to make about such things as electability and character, judgements that ended up leaning more and more toward Lincoln.

In The Lincoln Miracle, Achorn goes step-by-step and day-by-day into the work and maneuvering that went on at the convention to put Lincoln in a position to challenge and finally beat Seward. But he has a bigger story to tell.

Achorn puts the convention into the context of the national battles over slavery, and he goes into great detail to spell out the national and local disputes that shaped the decision of the convention.

In doing so, he gives the participants their say, and some readers are likely to wish that the long quotations from political leaders had been trimmed down to essentials. In letting people like newspaper editor Horace Greeley and Chicago Mayor Long John Wentworth ramble on, Achorn seems to be aiming to reflect the intensity and wordiness of politics in that era.

“All the hogs ever slaughtered”

Yet, while giving space to the speeches, Achorn also gives space to vivid anecdotes and descriptions of people and events, and that is a great positive for his book.

For instance, during the nominating speeches, the Lincoln supporters vied with the Seward backers to shout the loudest, as Cincinnati newsman Murat Halstead recounted.

First, the Lincoln crowd: “No language can describe it. A thousand steam whistles, ten acres of hotel gongs, a tribe of Comanches, headed by a choice vanguard from pandemonium, might have been mingled with the scene unnoticed.”

Then, the Seward uproar: “Hundreds of persons stopped their ears in pain. The shouting was absolutely frantic, shrill and wild. No Comanches, no panthers ever struck a higher note, or gave screams with more infernal intensity.”

And, finally, the Lincolnites again: “Imagine all the hogs ever slaughtered in Cincinnati giving their death squeals together, a score of big steam whistles going…and you conceive something of the same nature….Many of their faces [in the Seward camp] whitened as the Lincoln yawp swelled into a wild hozanna (sic) of victory.”

“Sooty and scoundrelly in aspect”

Similar vivid language is used in describing the nominee — including by the nominee himself.

Achorn relates that, in 1841, a deeply depressed Lincoln told a friend, “I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on earth.” His law partner William Herndon said, “His melancholy dripped from him as he walked.”

When Lincoln’s picture circulated in the South after his nomination, a South Carolina editor wrote: “A horrid looking wretch he is! — sooty and scoundrelly in aspect…He is a lank-sided Yankee of the uncomeliest visage, and of the dirtiest complexion.”

Lincoln’s friends weren’t much more complimentary. When the committee of delegates came from Chicago to formally offer Lincoln the nomination, the man they found was, according to German-American leader Carl Schurz, “tall and ungainly in his black suit of apparently new but ill-fitting clothes, his long tawney neck emerging gauntly from his turned-down collar, his melancholy eyes sunken deep in his haggard face.”

“Unconscious instruments”

Schurz added that Lincoln “certainly did not present the appearance of a statesman as people usually picture it in their imagination.” Even so, this is the man that the Republicans had nominated, and Isaac H. Bromley, a reporter from Connecticut, suggested that, in doing so, the delegates may have been “unconscious instruments of a Higher Power.”

Years later, he wrote that they had “nominated the plain, every-day, story-telling, mirth-provoking Lincoln of the hustings; the husk only of the Lincoln of history. It took four fearful years to give the event its true relations and right proportions, and it was not until the veil was drawn by an assassin’s hand that the real Lincoln was revealed.”

Whether the Lincoln nomination was brought about by a Higher Power or not, it’s certain that no one at the Chicago convention and no one reading about it in the newspapers, not Seward or Davis or Lincoln himself, could imagine what the nominee would soon mean to the nation.

Readers today know — and know how important the convention decision was that put Lincoln on the road to the White House.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.15.23

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 5.26.23.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Great review of a compelling and immensely consequential story. Thanks!

Thanks, Jim.