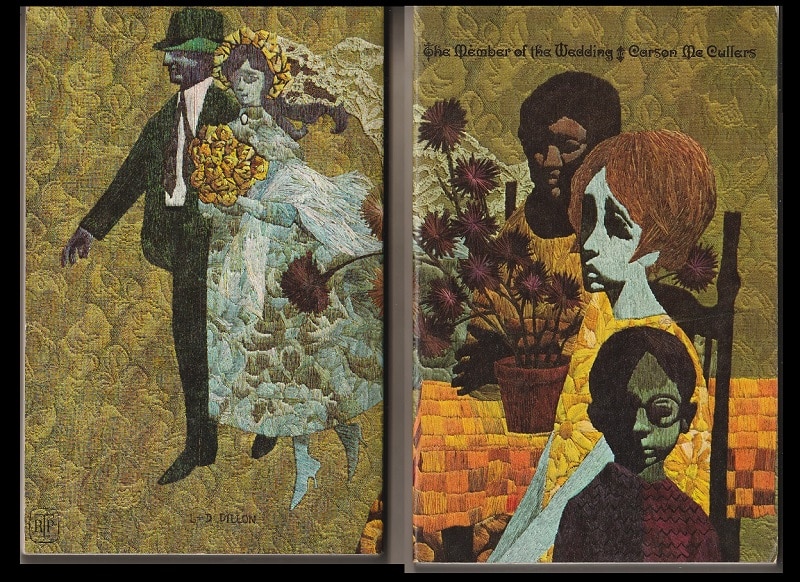

With its strangeness and ambiguities, with its dreaminess and veiled threats, Carson McCullers’s 1948 novel The Member of the Wedding has the feel of a book-length prose poem.

Certainly, a part of this is its rootedness in the Southern Gothic tradition. There are odd characters in a small Alabama town here although, truth be told, they’re not that odd. There are knives and a pistol that keep popping up, and, in fact, one of the characters is marked for a painful death. There is a “queer sin” in a garage. And a shocking incident in a hotel room.

Yet, this is a novel told from the point of view of twelve-year-old Frances Addams, and it could be considered a coming-of-age story except that, at the conclusion, there isn’t a sharp turn in the girl’s life. Just a bit one one.

The novel is told in three parts. In the first, she thinks of herself as Frankie. In the second and longest section, she is trying on a sort of clueless sophistication and calling herself F. Jasmine. In the final section, she is Frances.

She is a girl with a great imagination, and, it seems, she enjoys imagining her future more than living her present. Indeed, the novel is centered on her hopes and plans for an escape from her unsatisfactory life via the wedding of her soldier brother Jarvis to his girlfriend Janice.

Frankie — a girl who at the start of the book is no longer a member of any of the clubs and girlfriend groups to which she used to belong — has decided she will be a member of the wedding. But in a highly unusual way.

She has developed these hopes and plans without any consultation with the future bride and groom and refuses to listen to anyone telling her that they can’t come true.

A quirky, strong-minded, bored girl

The power of the book, I think, comes from the ability of McCullers to weave together Southern Gothic elements and coming-of-age aspects around a quirky, strong-minded, bored girl without strong attachments — or, at least, strong enough attachments — and with vague but powerful feelings of guilt.

The book opens on the kitchen in the family home:

She was in so much secret trouble that she thought it was better to stay home — and at home there was only Berenice Sadie Brown and John Henry West. The three of them sat at the kitchen table, saying the same things over and over, so that by August the words began to rhyme with each other and sound strange. The world seemed to die each afternoon and nothing moved any longer. At last the summer was like a green sick dream, or like a silent crazy jungle under glass.

But the announcement that her brother, back for a visit from his military base in Alaska, was to be married changed all that although, at first, Frankie couldn’t decide how.

It was four o’clock in the afternoon and the kitchen was square and gray and quiet. Frankie sat at the table with her eyes half-closed, and she thought about a wedding. She saw a silent church, a strange snow slanting down against the colored windows….There was something about this wedding that gave Frankie a feeling she could not name.

“The who she was”

Berenice was the Black cook for Frankie and her father Royal — Frankie’s mother had died at the girl’s birth — and “was very black and broad-shouldered and short.” She had been saying for three years that she was 35, and the only thing wrong with her was that “her left eye was bright blue glass,” the result of a violent ex-husband.

John Henry had a chest that, on this afternoon in the kitchen, “was white and wet and naked, and he wore around his neck a tiny lead donkey tied by a strong.” He was Frankie’s first cousin and small for being six years old and had “a little screwed white face and he wore tiny gold-rimmed glasses.”

And it isn’t long before Frankie determines what she will do about the wedding:

Frankie stood looking into the sky. For when the old question came to her — the who she was and what she would be in the world, and why she was standing there that minute — when that old question came to her, she did not feel hurt and unanswered.

At last she knew just who she was and understood where she was going. She loved her brother and the bride and she was a member of the wedding. The three of them would go into the world and they would always be together. And, finally, after the scared spring and the crazy summer, she was no more afraid.

“We all of us somehow caught”

Berenice and John Henry are witnesses and a kind of Greek chorus commenting on the efforts of Frankie, soon F. Jasmine, to escape the town — and all those questions about who she was and what she would do with her life.

The middle part of the story is filled with her scheming to figure out a way to ensure that Jarvis and Janice will agree to have her as their companion. It is during this period that she has long conversations with Berenice and John Henry about how oppressive she finds life as well as about her fleeting glimpses of human connection.

When F. Jasmine talks feverishly about all that she will do with Jarvis and Janice, Berenice sits her down on her lap and comforts her, saying:

“I think I have a vague idea what you were driving at. We all of us somehow caught. We born this way or that way and we don’t know why. We caught anyhow. I born Berenice. You born Frankie. John Henry born John Henry. And maybe we wants to widen and bust free. But no matter what we do we still caught. Me is me and you is you and he is he. We each one of us somehow caught all by ourself. Is that what you was trying to say?”

F. Jasmine says she doesn’t want to be caught. Berenice says she doesn’t either and she’s caught more than the girl and John Henry:

“Because I am black. Because I am colored. Everybody is caught one way or another. But they done drawn completely extra bounds around all colored people. They done squeezed us off in one corner by ourself. So we caught that first-way I was telling you, as all human being is caught. And we caught as colored people also.”

Embodiment of every preteen and teen

In the 1960s when I was in high school and college, A Member of the Wedding seemed to be on many school reading lists. I’m not sure if it still is. I suspect not.

For one thing, many African Americans today argue that they are the ones who should tell the stories of Blacks, not whites, no matter how well-meaning. And such stories are being told today about Blacks by Blacks and being published widely. That wasn’t the case in 1948 when McCuller published her book.

The question of being caught, though, no matter the circumstances of your birth, is certainly a worthwhile issue to be confronted by readers in their teens or at whatever age.

Frankie in her quirkiness is, in a way, the embodiment of every preteen and teen inasmuch as every preteen and teen is highly individual. Each faces some rock bottom challenges as how to deal with puberty and how to deal with approaching adulthood, but each does it in a distinctly personal way.

My suspicion is that it might be reassuring for a preteen or teen to read about a Frankie who, essentially, is wandering somewhat blind through a forest of such challenges.

This is a book that, I suspect, could capture the attention of many young people, even if it isn’t as culturally relevant as more modern book.

And not only teens. It captured my attention in my 70s.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.14.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.