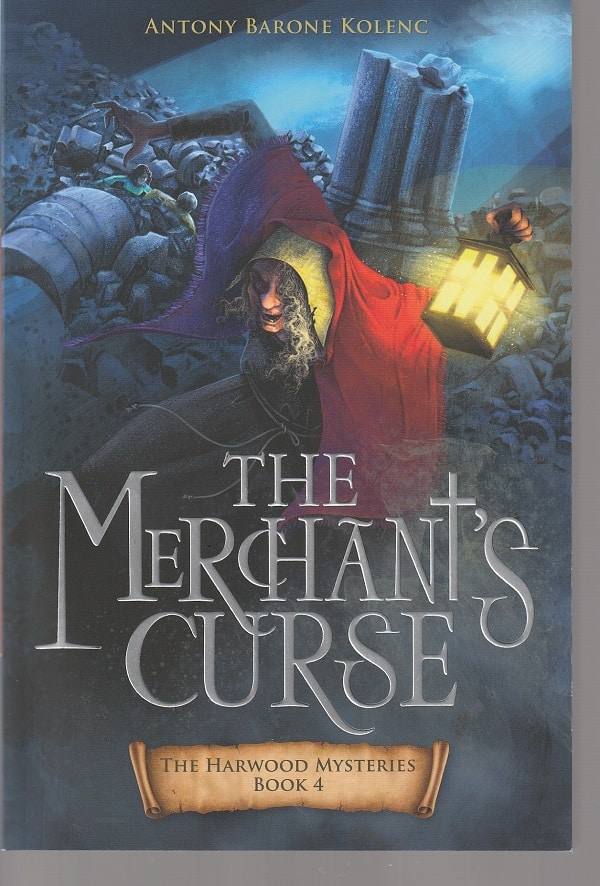

Antony Barone Kolenc’s The Merchant’s Curse is a historical mystery with a strong supernatural element, set in 12th-century England and written for children and young teens.

Even more, it’s a kind of morality play, designed to teach lessons about faith and right living.

This is a book written for a Christian readership from the Catholic publisher Loyola Press, headquartered in Chicago. It’s the fourth installment in Kolenc’s popular series of Harwood Mysteries, all centering on Xan, a young orphan. The earlier three in which Xan is living at Harwood Abbey are Shadow in the Dark (2020), The Haunted Cathedral (2021) and The Fire of Eden (2021).

“Yer pride and mocking will cease”

In The Merchant’s Curse, the 13-year-old Xan has come to the English town of Lincoln as an apprentice to his Uncle William — a merchant but not the merchant of the title. That’s Godric, William’s partner in business.

Early on, Godric, at a joke from his nephew Nigel, laughs at a strange, scary, disfigured woman — many people call her a witch — outside a poulterer’s shop. In response, she dips her fingers into the draining blood of a hen’s carcass and limps toward him as if to attack:

But the woman apparently had no intention to strike Godric. Instead, she took the blood on her fingers and wiped it on him, making an “X” on both his wrists. He had held them high before her, as though inviting her to apply the blood in some foul ceremony…

“Mark my words! Within a week’s time, yer pride and mocking will cease as yer strong body withers and becomes weak like the blood of this hen.”

A second curse

That’s the curse. And, soon, Godric is vomiting at every turn and, sure enough, wasting away.

So, too, is Xan when he follows Nigel to the woman’s shack and she goes after them, splattering Xan’s face with hen’s blood and cursing him as well.

Meanwhile, Nigel, a merchant allied to his uncle, is flirting with Duke Geoffrey, the son of King Henry who is rebelling against his father. And that could get him and everyone in his circle, including Xan and William, hung as traitors.

And Xan sees two henchmen of the secretive moneyman known as the Master hanging around William’s shop, and he fears that his uncle has gotten deep into debt once again with potentially violent consequences.

And Xan’s from-afar affection for the red-haired Christina seems doomed since Nigel is wooing her with a promise of a life of wealth and ease.

“Power of good?”

All of these elements make for an adventure that picks up its pace in the second half of the book as plot twists multiply, all of which is typical of many novels written today for children and young teens.

What’s different, though, is that morality-play aspect to The Merchant’s Curse. Kolenc’s story isn’t just escapism, but also instruction.

The key to all of these mysteries seems to be the scarred woman, and Xan, who has shown a knack for solving such puzzles in the earlier books in the series, rises from his sick bed to try to figure out this one:

Of course — he must still solve the mystery of this witch. Maybe that was why God had sent him to Lincoln. Why was it that her wicked curse could not be overcome by the power of prayer and the power of good? That made no sense: good always defeated evil; prayer always prevailed over curses. Then why was evil winning?

Countercultural

Much popular fiction of all sorts today focuses on the supernatural. In some cases, it has to do with magic. In many others, it is about eerie, spooky, frightening stuff — ghosts or demons or mythical creatures, such as vampires.

The Merchant’s Curse is countercultural inasmuch as it addresses the aspects of the supernatural from the perspective of religious faith. It envisions a world in which evil exists, but also where God exists.

Xan is searching to solve mysteries not just to satisfy his curiosity or to avoid doom, but, above all, to figure out what God wants him to do in his life.

Indeed, as much as The Merchant’s Curse is about Xan’s adventures, it’s even more about his meditations on a book from the Hebrew Bible. As Kolenc, a retired lieutenant colonel from the United States Air Force Judge Advocate General’s Corps, explains:

With The Merchant’s Curse, I finally had the chance to write a story that explores the themes of my most beloved Old Testament book: Ecclesiastes….The idea of “vanity of vanities!” permeates Book 4 and finds its way into the situations confronting the key characters, including Xan’s search for wisdom like King Solomon’s.

Believing

Readers of most novels dealing with the supernatural don’t have to believe in demons or ghosts to enjoy the frightening story.

With The Merchant’s Curse and the other titles in the series, it’s different. After all, Kolenc’s goal isn’t simply to titillate his readers. His aim is to use his story as a parable, as a morality play.

A book about vampires isn’t aimed at convincing the reader to believe in vampires. But Kolenc is serious about the religious underpinnings of his story.

He’s a believer, and he wants his reader to believe as well.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.13.22

This review initially appeared at Third Coast Review on 10.24.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.