When Lew Archer first sees Miranda, the daughter of the missing millionaire Ralph Sampson, he has her pegged:

I watched her over my salmon mayonnaise; a tall girl whose movements had a certain awkward charm, the kind who developed slowly and was worth waiting for. Puberty around fifteen, first marriage or affair at twenty or twenty-one. A few hard years outgrowing romance and changing from girl to woman; then the complete fine woman at twenty-eight or thirty. She was about twenty-one, a little too old to be Mrs. Sampson’s daughter.

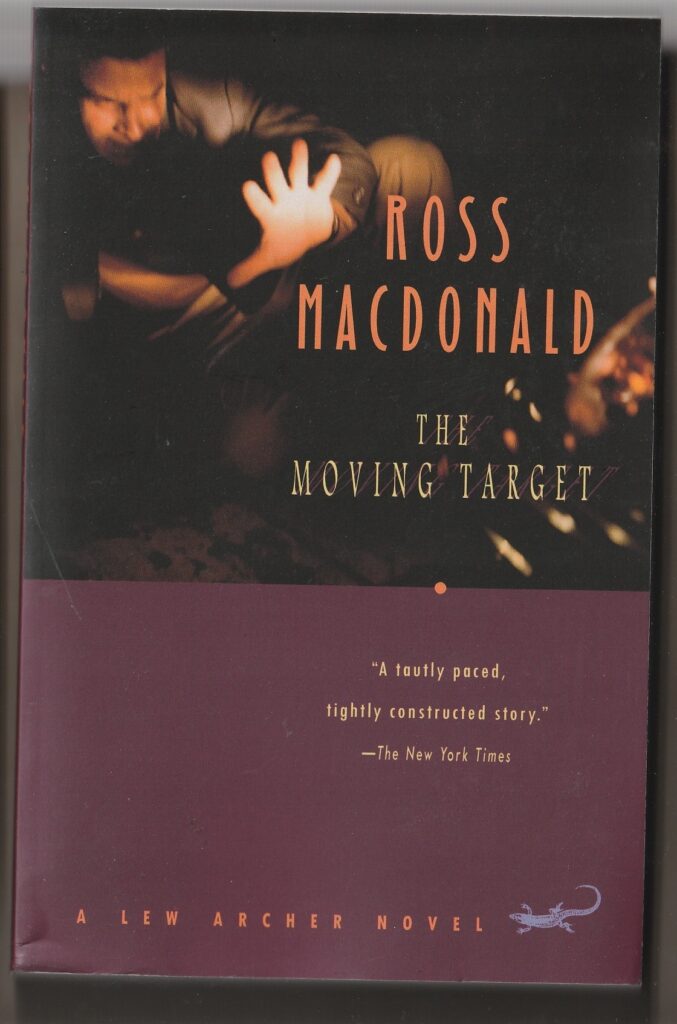

Throughout The Moving Target (1949), the first of Ross Macdonald’s eighteen Archer novels, Miranda is bantering in a flirtatious way with the private detective while also hankering for her father’s pilot and go-fer Alan Taggert and being hankered after by Bert Graves, the family lawyer who keeps asking her to marry.

Archer has come up from Los Angeles to Santa Teresa (a stand-in for Santa Barbara) because Miranda’s stepmother, Elaine Sampson, who gets around in a wheelchair, wants to find out why her husband disappeared after landing at Burbank airport.

While a savvy, serious businessman, Ralph Sampson, from what Archer can determine, is a bit flakey, especially when he’s drinking. Such as giving away a mountain, complete with a hunting lodge, to a “Los Angeles holy man with a long gray beard,” whose name is Claude.

“A moving target”

It’s about midway through the novel when Miranda is driving Archer up to that hunting lodge, now something of a religious retreat, that the book’s title phrase is first used.

Miranda, who has read a lot of psychology books, is sparring with the thirty-five-year-old detective:

“I’ve done a hundred and five on this road in the Caddie.”

The rules of the game we were playing weren’t clear yet, but I felt outplayed. “And what’s your reason?”

“I do it when I’m bored. I pretend to myself I’m going to meet something — something utterly new. Something naked and bright, a moving target in the road.”

A short while later, they are at the lodge, going through the rooms looking for Miranda’s father or some clue of where he might be, and are still bantering:

“You make me sick, Archer. Don’t you get bored with yourself playing the dumb detective.”

“Sure I get bored. I need something naked and bright. A moving target in the road.”

“You!” She bit her lip, flushed, and turned away.

Later that afternoon, as they are driving back through fog to the Sampson mansion, their car is nearly sideswiped by a dark limousine, driven by a guy with a thin, pale face, the same sort of car and driver who’d picked up Miranda’s father at the airport.

Archer is angry that he can’t give chase.

“What on earth’s the matter? He didn’t actually crash us, you know.”

“I wish he had.”

“He’s reckless, but he drives very well.”

“Yeah. He’s a moving target I’d like to hit some time.”

When they get to the house, there’s another important reason why stopping the limo would have been a break in the investigation. There in the mailbox slot is a ransom note.

The game keeps changing

This first of the Archer novels is all about moving targets. His investigation keeps changing because the rules of the game keep changing.

At first, it’s about a disappearance. Then, it’s about a kidnapping, and human trafficking, and one murder, and a drowning, and the killing of a guy aiming a gun at Archer, and then a second murder, and, throughout, it’s about betrayal upon betrayal.

The bad guys — men and women — betray each other. It’s all about opportunity and a ransom of $100,000 which is $1.3 million in today’s dollars.

And even a good guy gets tempted. And Miranda’s heart gets broken.

Quick on his feet

In this debut novel of the series that would run for twenty-seven years, Macdonald establishes Archer as a guy quick enough on his feet and in his mind to handle a lot of moving targets.

He’s also a guy who, as his interactions with Miranda show, is attuned to the nuances of human nature, both good and bad, especially his own.

Such as on that drive to the lodge when Archer advises Miranda to take time to live life as it comes:

“You can’t speed up time. You have to pick up its beat and let it support you.”

“You’re a strange man,” she said softly. “I didn’t know you’d be able to say things like that. And do you judge yourself?”

“Not when I can help it, but I did last night. I was feeding alcohol to an alcoholic, and I saw my face in the mirror.”

“What was the verdict?”

“The judge suspended sentence, but he gave me a tongue-lashing.”

A poet’s eye

Finally, Archer is a guy with a poet’s eye. Such as when his investigation takes him to a bar called the Wild Piano:

The night was no longer young at the Wild Piano, but her heartbeat was artificially stimulated. It was on a badly lit sidestreet among a row of old duplexes shouldering each other across garbage-littered alleys. It had no sign, no plastic-and-plate-glass front. An arch of weather-browned stucco, peeling away like scabs, curved over the entrance.

At one point, he tells the reader that Miranda “moved like a live young nymph in a museum.” At another, he describes driving along the ocean:

There was a traveling moon in the clouds, which were drifting out to sea. Its light on the black water made a dull lead-foil shine.

And here is how he describes his flight from Santa Teresa to Los Angeles:

We rose into the offshore wind sweeping across the airport and climbed toward the southern break in the mountains. Santa Teresa was a colored air map on the mountains’ knees, the sailboats in the harbor white soap chips in a tub of bluing. The air was very clear. The peaks stood up so sharply that they looked like papier-mache I could poke my finger through.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.23.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.