The Pueblo boy with “thick hair…the color of a night river” is called Wolf.

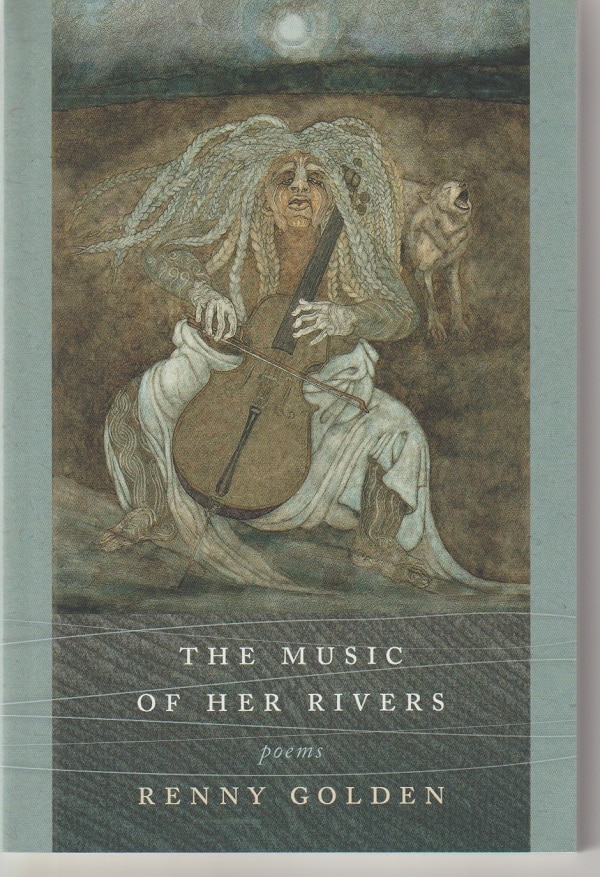

He appears several times in the first half of Renny Golden’s The Music of Her Rivers, her gathering of radiant poems about lives on the hard edge of America (University of New Mexico Press, 87 pages, $18.95).

In “They Named Me Wolf,” the boy looks forward to the day when he will become a man and do the things that men do, such as digging a link so the Rio Grande’s “star-flecked waters” will flow into irrigation channels.

I speak for this river carrying the stillborn, the dying —

this water that quenches the thirst of bosque, mergansers,

warblers, and ash-throated flycatchers.

Like Wolf, Renny Golden speaks for this river and all the other rivers where those pushed to the margins of U.S. society find homes and work.

Even more, she speaks for those marginalized people — the Native Americans like Wolf, the immigrants from Mexico (with and without documents), and, along the rivers of her home Chicago, the Irish and African-Americans and Latinos and the blue-collar workers whose days are rivers of toil and endurance.

”Bruised hands gut meadow”

Modern American politics is built around wedge issues — about driving people apart, about pitting this group against that group.

Golden, though, sees deeper. She sees how much the seemingly disparate peoples have in common.

This is a theme in “Magicians,” a poem about the building of the Illinois & Michigan Canal, linking the Chicago River and the Mississippi, carried out by Irish immigrants and former slaves, starting in 1836.

We, the anonymous, caked in dirt.

Bruised hands gut meadows of canary weed,

sedge marsh alongside dark men with scarred

backs, lashed by a deeper servitude…

We are the nameless, who made

a silver highway for freight boats

pulled along towpaths by mules like us.

“Mules like us”

In these poems, Golden speaks for “the anonymous” and “the nameless.”

If you’ve ever been to one of those ribbon-cutting ceremonies where besuited men and high-heeled women, all with clean hands, wear uncomfortably fitting hardhats to show that work has been done and will be done, and they all smile broadly, pols and power brokers.

And the work is done by “mules like us.”

And the work is done by “mules like us.”

“Who lost”

Look at Chicago’s skyline. In “What the River Said,” Golden writes that its message is:

The city muscled and bullied skyward.

She, though, hears voices that say something else:

The river, our sheanachi [Irish storyteller] and griot [African storyteller], keeper of myth

tells the other story: who lost.

And Golden adds:

This river tale is mine, is Chicago’s, a history

as unsung as any in the flashpan of America’s

rise from prairie and stream to a city

torn between the labor of slaves and immigrants

and the blueprints of city barons.

Silence slips the tumult of progress,

this wordless language of rivers

ever moving through dappled light.

“And as betrayed”

Golden invites her reader to listen to “this wordless language of rivers.”

She listens, and, in this language, she hears the voice of God. Through Wolf, she asks:

What if the Sacred is a river cluttered

with rusted batteries, tires, paint cans,

bones of horses, oil, solvent, plastic bottles?

She rides on, cagey in her silence,

faithful as the wolf and as betrayed.

Can a God be betrayed?

Can Nature be betrayed? By the cluttering of a river “with rusted batteries, tires, paint cans,/bones of horses, oil, solvent, plastic bottles”?

“A fight that will be their choice”

Are the poor betrayed? Those hired to do the dirty jobs or not hired or unhired when it would get in the way of stockholder dividends?

These are the people of The Music of Her Rivers — those from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras and other southern countries, as well as the Irish immigrants of her forebears and the descendants of blacks kidnapped in Africa and sold into slavery.

In “Na Geill, Nunca Abdicacion (Never Surrender),” Golden celebrates the Irish-immigrant soldiers in the American army who, in 1847, in the Mexican-American War, decided they had more in common with the those they were fighting than with their Papist-hating generals.

So, one day, the San Patricios, as they are called, swim south across the Rio Grande to join the Mexicans and “a fight that will be their choice,” battling for “a land of familiar chaos/poverty, ghosts, and rosaries.”

Like many of the people in Golden’s book, the San Patricios and their Mexican leaders find the odds are stacked against them. And no quarter is given. Literally.

On Scott’s orders, the San Patricios are to be hung publicly while watching

Mexico’s flag sinking and the American flag rising. Fitting last blow.

Patricios, feet and hands bound, ropes on necks, cheer the Mexican flag.

America’s flag rises in a strangled silence that envelops the vanquished air.

“Risked limbs”

For me, the most poignant and pointed poem in The Music of Her Rivers is “Steel Mills” which most directly describes the common toils and the common hopes of the many different groups who share the margins of U.S. society.

The steel mills, Golden writes, are where

Our fathers poured the gold like priests

transubstantiating molten for the world’s architecture.

Each day, those fathers strode into the plants, with all their roar and clamor,

where they risked limbs for the purchase

of a southside bungalow. Men whose

blunt fingers played accordions in Polka bands,

blues harmonicas at Theresa’s Club,

bodhran and fiddle at O’Halloran’s

whose hands worked shearing machines,

flywheels, cooling beds, gear boxes.

That music, too — of the accordions, of the harmonicas, of the bodhran and fiddle — was the music of God’s rivers, the music of God, the music of losing and enduring and hoping.

The music of the mules.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.29.20

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 12.12.19.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.