American thrillers tend to be strictly for entertainment.

Oh, yes, there may be a subtext message to the reader that, if you don’t do something about something — such as global warming or international arms dealers or plagues or threats to democratic institutions or incipient totalitarianism or nuclear weapons — this novel shows the doomsday scenario that you will face.

But, really, American thrillers aren’t for teaching. They’re to entertain, to keep the reader turning the pages like mad to see what’s going to happen.

And they tend to be very serious. After all, the catastrophic calamity that is at the heart of all such thrillers is, well, catastrophic, which is to save very, very serious.

So the writing of American thrillers tends to be very tightly focused on the plot and on maintaining a propulsive momentum, often with a clock ticking down to a horrible denouement, to hurtle the reader along. For this reason, such niceties as fleshing out the personalities of the characters and taking a moment to describe with interesting detail a place or a scene usually go by the wayside.

It’s called a thriller for a reason. It’s supposed to be thrilling!

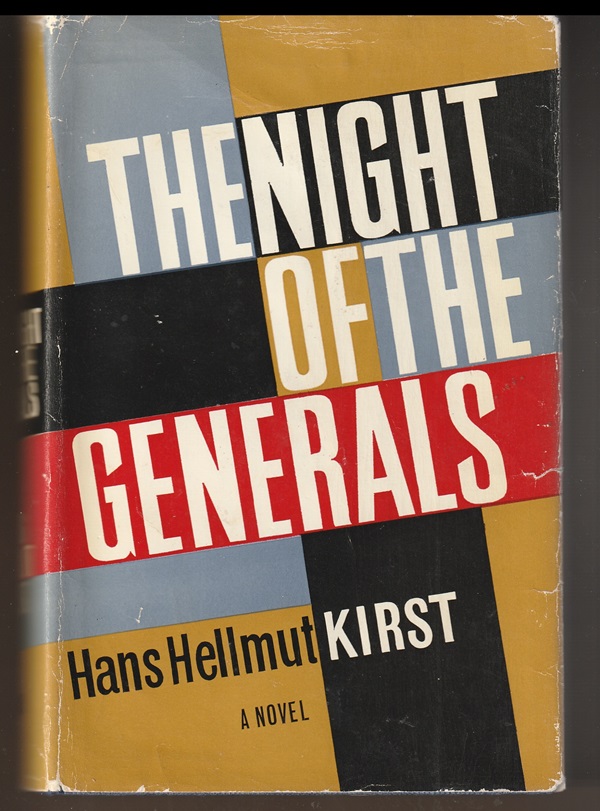

Hans Hellmut Kirst’s The Night of the Generals, published in English in 1963, was marketed in the United States and the United Kingdom as a thriller. For instance, the dustjacket on the British hardcover announced:

The Night of the Generals is a spell-binding piece of story-telling with all the elements of a thundering good thriller.

But it is a novel that is much more complex than the usual American thriller.

“A red stripe”

Even so, just to be clear, Kirst’s book is certainly thrilling. Like its U.S. counterparts, it pulls the reader along through more than 300 pages of a complex plot, involving the brutal butchery of three bad-luck prostitutes in three European cities (Warsaw, Paris and Dresden) on three different occasions over a fourteen-year period.

In each case, the victim is savagely mutilated in her own room in the dark of night, and the reader knows, from the opening pages, that the killer is a German general.

The reader knows this because, after the first murder in 1942, the Polish and German cops find a witness.

From his perch on the communal toilet in the rundown building, Henryk Wionczek peered through the large keyhole of the toilet door to see the killer leaving. He was wearing, the witness said, some kind of German uniform:

“It could have been a German officer,” said Wionczek. Words suddenly gushed from him like water from a spring. “At least, that’s what I thought at the time. Of course, I could be wrong. I was in a bit of a state — not feeling too good — that’s why I was sitting there in the first place. Anyway, I caught sight of something else, something red, like a red stripe running down the man’s trouser-leg — a wide red band. And there was something that looked like gold up by his collar.”

Unknowingly, he is describing the uniform of a German general.

Major Grau, the head of German counter-espionage for the Warsaw area, believes him, and so does the Detective-Inspector Roman Liesowski of the Warsaw police. And investigators quickly determine that, on the night of the killing, seven generals were in Warsaw. Four had alibis, and three didn’t:

- General Herbert von Seydlitz-Gabler, the head of a Corps.

- Lieutenant-General Wilhelm Tanz, commander of a special operations division and a favorite of Adolf Hitler.

- Major-General Klaus Kahlenberge, von Seydlitz-Gabler’s chief of staff.

This is where Kirst’s title comes from. Three generals, one night of murder.

Who is the killer?

In the typical American thriller, the reader would be on pins and needles to the very last pages, wondering which of these three was the killer. And, in the first half of The Night of the Generals, there is a lot of uncertainty.

Major Grau is trying to find out what each had been doing that night, but they aren’t cooperating. About a third of the way into the novel, he and his colleague Gottfried Engel come up with some preliminary findings, as Engel summarized many years later:

- General Herbert von Seydlitz-Gabler: “One of the old school, with all its virtues and vices. He’d really have been more at home in the last century. His wife was the power behind the throne, and there must have been times when he hated her guts.”

- Lieutenant-General Wilhelm Tanz: “A career-general of the first order with no inhibitions whatsoever. Rose from the ranks of the Freikorps and had just what it takes to go places. There were only two alternatives for him: a cross on his chest or another over his grave. He had an almost legendary reputation, and anyone who didn’t help to foster it became his personal enemy.

- Major-General Klaus Kahlenberge: “Middle-class origins. Hard to sum up. Kept himself and his opinions very much to himself. No one really managed to get to the bottom of him…He was the real brains of the outfit. He certainly acted as von Seydlitz-Gabler’s throttle and brake, and for all I know he may have steered him as well.”

And, then… Well, the vagaries of the war bring the investigation to a halt — until, two years later, when the three generals and Major Grau end up in Paris.

And another mutilation-murder takes place.

“Greater Germany”

By this point, the reader knows that Kahlenberge very much has been steering his superior in making decisions.

By this point, the reader knows that Kahlenberge very much has been steering his superior in making decisions.

The reader knows that von Seydlitz-Gabler is pretty much of a fool — not exactly a doofus, but a political-minded, status-worried general whose wife knows how to play the system with vicious ambition.

And the reader knows that Tanz is a self-deluding zealot:

Tanz looked like a painting by someone who had tried to capture the essence of heroism. With his lithe athletic figure, slender boyish hips, gladiatorial width of shoulder and finely chiseled features, he gave the impression of being a successful cross between a mountaineer and a seaman. He towered above everyone around him.

Later, when a new orderly comes face to face with Tanz, he sees “a lean, angular countenance whose every detail was as clean-cut and precise as if it had been designed on a drawing-board.”

Later still, Grau, now a Colonel, confronts Tanz, only to be told:

“Colonel Grau, at this moment I am the embodiment of the Fuhrer’s will. An attack on me is an attack on Greater Germany, and anyone who tries to hinder my work automatically stands revealed as an enemy of the Third Reich. I would go further: anyone who tries to destroy me must necessarily be trying to destroy the sacred ideals which inspire our great nation.”

Using the thriller for many purposes

Everything about Tanz is out-size, exaggerated, over the top. Together with the buffoonish von Seydlitz-Gabler and the slippery-slidey Kahlenberge, these three generals provide a parody of the German military leadership in World War II.

And that’s Kirst’s focus early on: the silliness of the internal military politics and the big-headed, warrior-persona that Tanz inhabits — all in contrast to one mutilation-murder and, then, a second.

Then, about two-thirds of the way through the book, the three generals, each in his own way, become involved, on one side or the other, of the assassination plot against Hitler.

And it is at this point that Kirst makes clear to the reader which general is the one killing prostitutes. (But his comeuppance won’t happen until 12 years later in Berlin after yet another killing.)

Revealing the killer this early is one of the many indications that Kirst isn’t simply writing a thriller. He is using his thriller for many purposes: to make fun of the German military leaders in World War II, to find fault with their willingness to follow Hitler as a leader (and then, finally, when they take action, botch up their assassination attempt), and to condemn Tanz’s mindset of himself as a military machine as well as those soldiers under his command.

Written more than sixty years ago, The Night of the Generals still resonates today as an anti-war novel — and a novel that honors, above all else, the rule of law.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.23.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Hello Patrick, I first saw the film, starring Peter O’Toole asSS General Tanz, and Tom Courtenay as Army Lance Corporal Kurt Hartmann . I actually think that the film is better than the book is some aspects. Some of Abwehr Major, later Colonel, Grau comments in the film are illuminating, and the film’s ending is definitely better than the book. Having said that, I enjoyed the book immensely, and went on the read another dozen H H Kirst books..

Thanks, Philip. I haven’t seen the movie so I’ll give it a try.