Robert Ludlum had a knack for writing successful and very popular thrillers, producing 27 books with a total of somewhere between 300 million and 500 million copies in print.

That resulted in a ton of money, and what’s notable is that Ludlum has continued to make a ton of money even though he died in 2001 at the age of 73.

A year after his death, his books got a new boost in popularity when the slick, fast-paced well-received The Bourne Identity, starring Matt Damon, was released. The film, based on Ludlum’s 1980 novel of the same name, was the first of a five-part sequence of films that have been huge critical and commercial successes, netting more than $1.6 billion worldwide.

Beyond that, Ludlum’s heirs have continued to publish books — 29 so far by 10 different authors — under the trademark inscription of “Robert Ludlum’s.”

That’s not much of a stretch, the idea that a professional writer could produce a Ludlum-like novel. After all, he followed a formula that they can also easily follow.

Basically, a Ludlum or Ludlumesque novel has a hero struggling against powerful foes conspiring to promote their own gain and other evil intentions while corrupt democracy and the rights of the average Joe. There’s always a lot of skullduggery in the shadows by the evil guys and a lot of confusion on the part of the hero who is trying to figure out why a lot of bad things are happening around him. A lot of paranoia.

As I say, it’s a formula that’s been hugely successful.

So why did I come away from The Osterman Weekend disappointed?

Muddy, convoluted, far-fetched

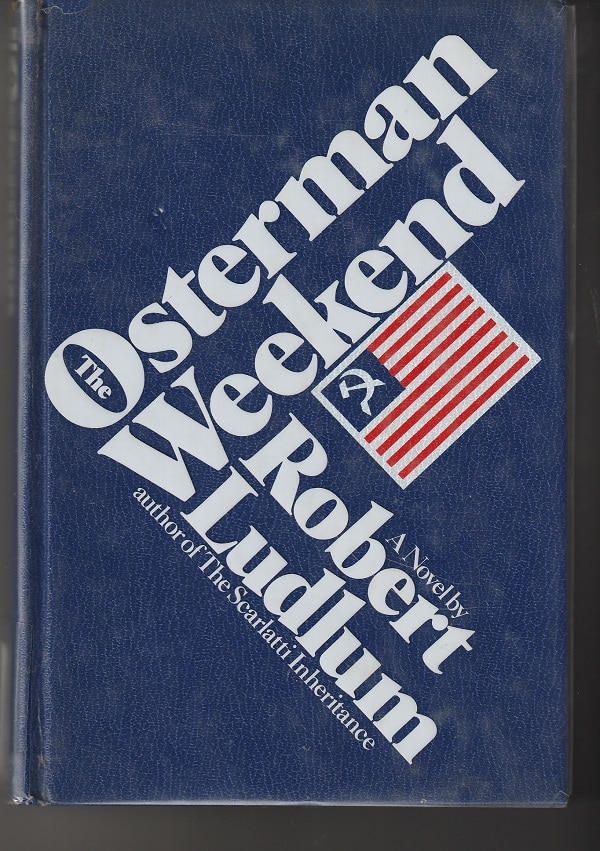

The Osterman Weekend was Ludlum’s second novel, published in 1972, a year after his first, The Scarlatti Inheritance.

At some point in the 1970s, I read a lot of Ludlum’s books, and I have a vague memory that, somewhere in the middle of all this reading, I picked up The Osterman Weekend and was unimpressed. A half century later, I came across a paperback copy and thought to give the book another chance.

What I found, though, was a muddy, convoluted, far-fetched plot within a plot, featuring John Tanner, the news director of a major television network, recruited by a CIA operative to investigate three couples who are his close friends. They are, he’s told, part of Omega, a dastardly Communist effort to undermine the free world, and they are all about to gather at his home for their annual weekend together.

The telling of the story is overly complex because Ludlum has to make Tanner a believable and interesting character, but not only him. The other members of the couples, men and women, have to be sketched as people the reader can relate to in some way, as somewhat everyday Americans who could just as well be your next door neighbors and may or may not be spies.

That gets pretty complex for Ludlum. And among the many signs of this novel’s age is its treatment of women as secondary members of society — and the shock that Tanner has when he begins to believe that the mastermind of Omega might be the wife (!) of one of his male friends.

Violence happens here and there, and it’s awkwardly presented and described. Nonetheless, in the final third of the book, the pace of Ludlum’s story quickens, and he drags the reader along. What will come next?

The ending is a kind of a surprise but also a bit anticlimactic. Answers are given, but there are too many of them — there’s no elegance to the story or its telling — and they’re too clumsy.

Stoking paranoia

My theory is that The Osterman Weekend is an indication that, in 1972, Ludlum was still learning his craft.

I don’t remember enough about the novels I read in my 20s to know what he did better in his later books, but it’s clear that he got his act together.

Suggesting conspiracies and stoking up paranoia made Ludlum and a lot of other people a ton of money.

It can also be a formula in politics, but that’s another story.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.14.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.