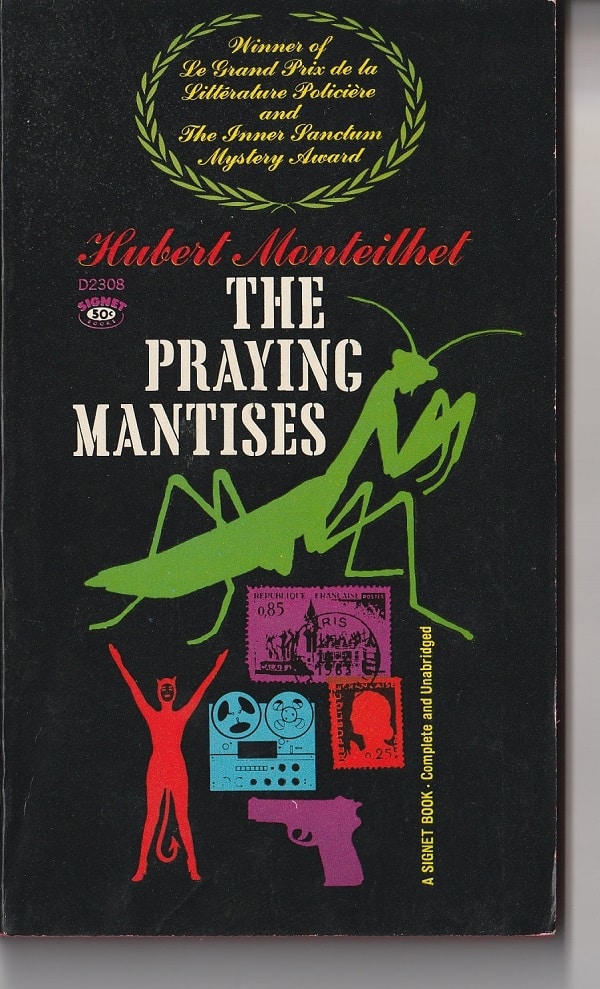

At some point, near the end of Hubert Monteilhet’s The Praying Mantises, one character says to another:

“You’re the worst of the three of us.”

That’s saying a lot. By this point, the reader knows just how cruel, amoral, conniving and evil all three of the book’s central characters are.

Which is to say the book’s three murderers:

- Vera Canova, 31, the wife of Paul Canova, 51, and stepmother of Xavier Canova, 9.

- Christian Magny, 34, Paul Canova’s university colleague.

- Beatrice Manceau, 20, the footloose and fancy-free woman who, pregnant by another man, jumps at Magny’s offer of marriage and goes through with it even after her miscarriage.

At this point in the 1960 novel — when she’s called “the worst of the three of us” — Beatrice does have the upper hand, but that’s only because Christian and Mme. Canova made the miscalculation of underestimating her.

They’re the ones — actually, it was Mme. Canova, pretty much by herself — who came up with the original plan for the three murders. Well, actually, it was supposed to be four.

In any case, it won’t spoil the story to say who the victims are:

- Xavier Canova

- Paul Canova’s secretary Gertrude Sourisseau

- Paul Canova

Actually, that’s not the end of the deaths. Later, there’s another murder and two suicides. (And, actually, there may have been an earlier one as well.)

Using documents to tell the story

The great distinction of The Praying Mantises — aside from the ruthless, unprincipled, malevolent threesome at the center of the narrative — is Monteilhet’s method of using documents alone to tell his story of Christian, Beatrice and Mme. Canova.

Some are communications within an insurance company over a huge policy that Paul Canova, a clueless, self-absorbed academic, buys in 1923. Others are newspaper articles. Some, suicide notes. A key document is Beatrice’s diary. Others are letters between different pairs of the murderers.

The book opens with the 1920s exchanges between Paul Canova and the insurance company for the policy of which his wife will be the beneficiary.

But the bulk of the novel is told through letters, reports and such from 1947 through 1950, starting with another letter from Paul Canova to the insurance people, noting that his first wife died in 1946 and, later that year, he’d married his second wife, the Russian-born Vera.

Odds are that, eventually, the reader of The Praying Mantises will come to the conclusion that Vera may have had a hand in that first wife’s death. But that would be sheer — if understandable — speculation. Monteilhet doesn’t hint at it. (Perhaps because he needn’t.)

At one remove and in the minds of the killers

Monteilhet’s storytelling-through-documents approach works wonderfully well for two reasons.

- One: It puts the action at one remove. The reader doesn’t watch the events happen in real time but learns of them through the words of participants, many of whom — the secondary characters — know only a small piece of the action. The reader, though, has been able to piece together a much more complete picture.

- Two: It paradoxically puts the reader inside the minds of the killers. Monteilhet is able to present the dry, flat words on the page and, at the same time, portray the sharp, jagged emotions of the three killers. It’s an amazing tour de force.

Of course, the title The Praying Mantises goes to the core of the novel. The female praying mantis is famous for her sexual cannibalism. During copulation, she is wont to bite off the head of her male partner.

So, the reader of Monteilhet’s novel won’t be surprised that Christian has a difficult time of it in the murderous threesome between Beatrice and Mme. Canova.

He’s essentially eaten alive.

Someone else’s private business

One final note about Monteilhet’s documentary style: It permits the reader to luxuriate in someone else’s private business.

The usual novel involves the writer speaking to the reader as if in a living room or around a campfire, telling the story. In this novel, it’s as if the reader has come into possession of a file folder thick with the stuff of other people’s lives.

Monteilhet hints at this in a Note that precedes the novel and suggests the value of such an approach:

We are aware of the fact that such literature, in our day, satisfies a heartfelt need on the part of the public; in a world where human nerves are under constant strain, nothing is more likely to soothe our cares than the innocent enjoyment of other people’s suffering. The morbid secretions of certain souls have the capacity to amuse decent men — an irreplaceable therapeutic virtue.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.21.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.