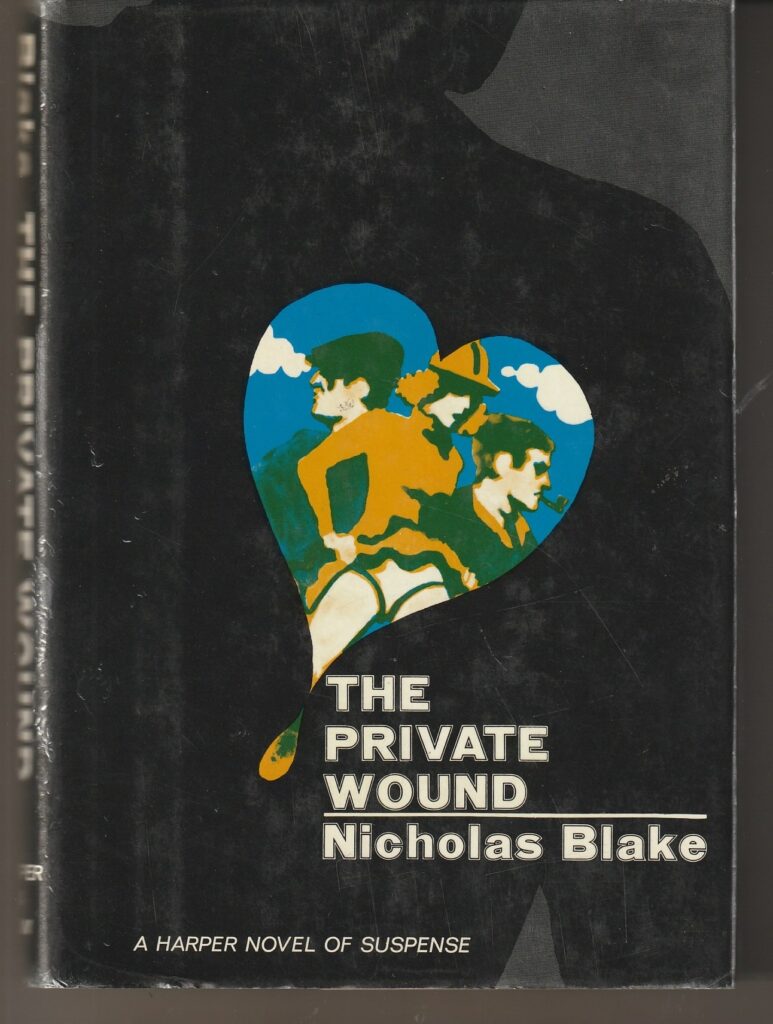

In the final pages of Nicholas Blake’s 1968 mystery The Private Wound, the killer is confronted by an accuser and spills out a detailed and brutal confession and then, in a long silence, stands there “shivering like a terrified horse.”

Quite an image, not the usual stuff of murder mysteries. But Nicholas Blake isn’t the usual author. In fact, he isn’t Nicholas Blake.

He’s the pen name of Irish-born British poet Cecil Day-Lewis. Day-Lewis — known better among present-day moviegoers as the father of Daniel — turned to writing crime novels as a way to boost his income as a poet, editor and university teacher at Cambridge and Oxford.

When he was publishing his poetry, essays and translations of such works as the Aeneid, and when he was publishing three novels for adults and two for children, he used his real name.

But, when he wasn’t aiming at art but rather at entertainment, Day-Lewis wrote as Nicholas Blake — 16 novels featuring the gentleman detective Nigel Strangeways and four other stand-alone works.

The Private Wound, one of those stand-alone books, was significant in several ways. It was published in January, 1968, when Day-Lewis began his term as Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, a post he held for four years until his death on May 22, 1972.

The novel was the last of the Nicholas Blake mysteries, and the second to the last of the books that Day-Lewis published in his lifetime, coming two years before The Whispering Roots and Other Poems. And The Private Wound was reportedly the Blake novel that Day-Lewis regarded most highly.

“Gouts of black blood”

The Private Wound is a fine mystery which is to say that it has interesting characters moving through an interesting plot that leaves the reader in suspense until the end.

Yet, it’s a cut above even the usual fine mystery.

Set in the summer of 1939, it tells the story of an English writer, Dominic Eyre, who, while staying in a small village in the West of Ireland, gets entangled with the wife of a former IRA commander, Harriet Leeson, known as Harry.

There is something tangible in Blake’s writing that stands out, such as his handling of a description. Consider these sentences from the first page of the novel:

I am lying on a bed drenched with our sweat. She is standing by the open window to cool herself in the moonlight. I see again the hourglass figure, the sloping shoulders, the rather short legs, that disturbing groove on the spine halfway hidden by her dark-red hair which the moonlight has turned black. The fuchsia below the window will have turned to gouts of black blood. The river beyond is talking in its sleep. She is naked. She turns her head to me and says, “Come on! You’re always best the third time.”

“The temple of the body”

While in the village, Eyre breaks off his long-distance engagement to a rich girl named Phyllis who’s on an around-the-world tour. Phyllis writes back releasing Eyre without rancor, and Eyre tells the reader:

But it never occurred to me that I might marry Harriet. She was a priestess in the temple of the body, adept and still a little mysterious: one does not marry priestesses.

By the late 1960s, sex scenes were expected in most “serious” mysteries, and Blake provides his share with great detail.

There is something else, though, that he provides to such moments from a deeper, more metaphysical place, such as this example: “We lie inert, side by side, not talking. Two animals which have escaped from time and the fear of the hunters.”

Again, not the usual fare in a crime novel.

“Like a granite rock”

Similarly, the relationships of the characters are much more complicated and nuanced than in the usual mystery. This is what Eyre is thinking about as he stands in the cemetery next to Harry’s husband Flurry, an erstwhile drunk.

I became aware of Flurry beside me, standing absolutely immobile, like a granite rock. It was thus that he would have faced an execution squad. No flinching, no prayers perhaps. I could not connect this hard man with the Flurry I had known for three months. It came to me in a revelation that I felt toward him now as a father figure: I had a son’s sense of guilt, no less for my past misunderstanding of him than for the wrong I had done him. I felt bound to him.

The Private Wound does all the things a mystery should do. It also does all the things that a well-written novel should do.

It’s so good that Cecil Day-Lewis could have left off the Blake pseudonym and used his own name on the cover.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.22.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.