The 18-year-old blond boy runs, and Detective/2nd Grade Steve Carella gives chase through the large city park.

He couldn’t understand why the kid was risking more trouble than a small narcotics buy was worth, but he didn’t stop to question motive too long. There was a time for thinking and theorizing, and a time for doing; and this was a time for using legs and not brains.

Carella takes a shortcut through deep trees and large boulders, swings around a giant outcrop of rock and screeches to a halt.

He was looking into the open end of a .32.

“Cops can get killed”

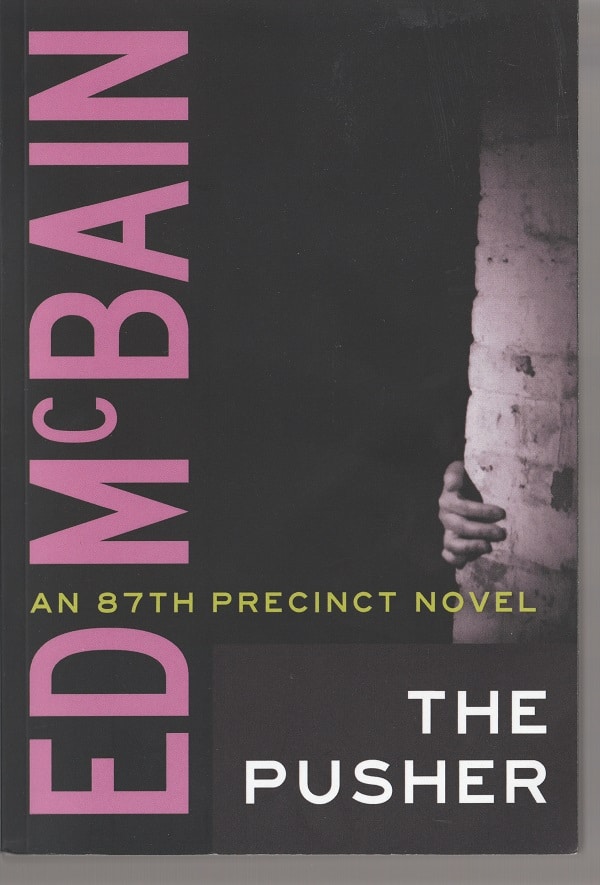

The Pusher was only the third 87th Precinct novel, the last of the three in Ed McBain’s original contract, all published in 1956. It would turn out that McBain — also known as Evan Hunter and multiple other authorial pseudonyms — would produce more than fifty.

But, already, Carella was the hero of the series.

That was odd inasmuch as the series was designed around an ensemble of detectives who made up the 87th Precinct squad room, “a conglomerate hero in a mythical city,” as McBain states in an Afterword to The Pusher. And he goes on to explain:

Meaning that one cop can step into the spotlight in one novel, another in the next novel, cops can get killed and disappear from the series, other cops can come in, all of them visible to varying extents in each of the books, all of the books set against the backdrop of a city with an invented historical past and place names that do not exist, all of which I’ve said two thousand times before.

(Although it should be noted that McBain’s “mythical city” certainly seems a lot like New York.)

Equal-er

So, yes, that was the series as McBain imagined it, and the series as it was carried out over 49 years in scores of installments: It was about the bulls in the squad room, each equally important to the make-up of the detective group, essential in that way, but, nonetheless, expendable at any moment.

And Steve Carella was as equally important to the series as any other detective in the room. However, already by this third book, he was a bit more — well, a lot more — equal-er than any of the others.

So, when Steve faces this kid’s gun, the reader is shocked.

And worried.

The broader universe of literature

While Steve’s confrontation with a .32 is the central moment in The Pusher, the novel, like all the others in the series, features the delightful grace notes that make McBain’s books more than simply crime novels.

Such as the way that McBain sprinkles throughout the story literary references as indications that, while this 87th Street series is part of the crime genre, it’s also part of the broader universe of literature. So, when he mentions the mythical city’s River Dix, it’s heard as an echo of the River Styx of Greek mythology.

And there are allusions to Shakespeare, such as “hoisted by its own petard” from Hamlet. And this one:

“Death had silently invaded the night, and death — like Macbeth — had murdered sleep….”

“Sue him?”

And then there’s a punk druggie who’s arrested and, when asked his name during questioning at the station, says:

“Ernest Hemingway. Listen, what’s with—”

Havilland slapped the boy quickly and almost effortlessly. The boy’s head rocked to one side, and Havilland drew his hand back for another blow.

“Lay off, Rog,” Carella said. “That’s his name. It’s on his draft card.”

The kid is mystified by all this and getting angry himself. What, he wants to know, is going on?

“There’s a fellow,” Carella said. “A writer. His name is Ernest Hemingway, too.”

“Yeah?” Hemingway said. He paused, then thoughtfully said, “I never heard of him. Can I sue him?”

“Candles”

Another nice wrinkle in The Pusher is its recognition that bad guys aren’t bad guys 24 hours a day, as Carella is thinking during a stakeout:

Do pushers have wives and mothers, too? Of course, they do. And of course they exchange Christmas gifts and they go to baptisms and bar mitzvahs and weddings and funerals like everybody else.

Later, as if to prove Steve’s point, a suspect is being questioned about where he was on a particular Sunday night:

“In church.”

“What?”

“I go to church every Sunday night. I light candles for my grandmother.”

“Magnificent birds”

Even the baddest of the bad guys in The Pusher is human in this way although, instead of candles and christenings, he and his affections are focused on pigeons, the ones he keeps on the roof, even during this very cold late December night:

Sure, pigeons are hardy, don’t they go gallivanting around Grover Park all winter long, but still he wouldn’t want any of his birds to die.

There was one in particular, that little female fantail, who didn’t look good at all. She had not eaten for several days now and her eyes, if you could tell anything at all from a pigeon’s eyes, didn’t look right. He would have to watch her, maybe get something into her with an eyedropper.

The other birds were looking fine, though. He had several Jacobins, and he would never tire of watching them, never tire of admiring the hood-like ruff of feathers they wore around their heads. And his tumbler, God, the way that bird somersaulted when it flew, or how about the pouters, they were magnificent birds, too, what the hell could Byrnes have up his sleeve?

Byrnes is a police lieutenant, Carella’s boss, and this guy on the roof is trying to ruin the life of Byrnes and everyone close to him and the cops in general.

He’s a very bad guy. Who happens to love pigeons.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.29.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.