To be precise, it was the Renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries that was the major “swerve” of European history — away from the church-dominated, faith-dominated, feudal Middle Ages and, ultimately, toward Modernity, a period that has included the Age of Reason, the Enlightenment and our present science-dominated, secular-centered, individual-centered times.

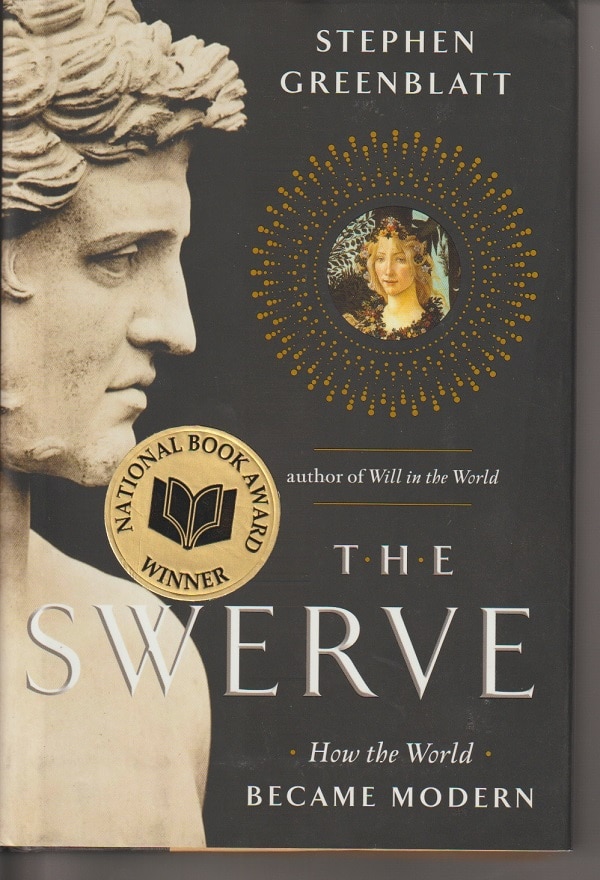

As Stephen Greenblatt explains in his 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, the term “swerve” comes from the Roman poet-philosopher Lucretius who used it in the first century BC in his book-length poem De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things). Greenblatt writes that Lucretius

“thought that nothing could violate the laws of nature. He posited instead what he called a ‘swerve,’ — Lucretius’ principal Latin word for it was clinamen — an unexpected, unpredictable movement of matter.”

According to Lucretius, everything that is in the Universe is made up of very small individual particles, also called atoms, and is created when “at absolutely unpredictable times and places [the atoms] deflect slightly from their straight course, to a degree that could be described as no more than a shift of movement.” This shift, or swerve, is very minimal, writes Greenblatt:

“But it is enough to set off a ceaseless chain of collisions. Whatever exists in the Universe exists because of these random collisions of minute particles. The endless combinations and recombinations, resulting from the collisions over a limitless span of time, bring it about that [as Lucretius writes] ‘the rivers replenish the insatiable sea with plentiful streams of water, that the earth, warmed by the sun’s fostering heat, renews her produce, that the family of animals springs up and thrives, and that the gliding ethereal fires have life.”

“Finally and forever”

The Renaissance was the swerve — really, a pretty sharp turn — away from the medieval view of humanity and life, and it occurred because a great number of much smaller swerves occurred, one of which was the rediscovery of the 7,400-line Lucretius poem On the Nature of Things — the story that Greenblatt’s book tells.

For a millennium, the Christian church and church-influenced thinkers and rulers worked to eradicate all traces of paganism — i.e., erasing not just the belief in gods other than the Christian God but also all aspects of science and philosophy that developed within the tolerant attitudes of pagan times, such as the Epicureanism at the heart of On the Nature of Things. Greenblatt writes:

“And with the rise of Christianity, [the Epicurean] texts were attacked, ridiculed, burned, or — most devastating — ignored and eventually forgotten. What is astonishing is that one magnificent articulation of the whole philosophy — the poems whose recovery is the subject of this book — should have survived….

“Of all the ancient masterpieces, this poem is one that should certainly have disappeared, finally and forever, in the company of the lost works that had inspired it.”

“The vital connection”

Indeed, Greenblatt notes that the efforts against Epicureanism were so great and so thorough that the poem’s survival might be called a miracle, except Lucretius didn’t believe in miracles. For him, there were swerves, and Greenblatt explains:

“The reappearance of his poem was such a swerve, an unforeseen deviation from the direct trajectory — in this case, toward oblivion — on which the poem and its philosophy seemed to be traveling.”

Greenblatt is enamored of the Lucretius poem and, it seems, is aching to give it the lion’s share of the credit for the dawning of the Renaissance and the reorientation of human thinking.

But he’s a scholar and knows he can’t overplay his hand. So, midway through his book’s preface, he writes:

“The line between this work and modernity is not direct; nothing is ever so simple. There were innumerable forgettings, disappearances, recoveries, dismissals, distortions, challenges, transformations, and renewed forgettings. And yet the vital connection is there.

“Hidden behind the worldview I recognize as my own is an ancient poem, a poem once lost, apparently irrevocably, and then found.”

A big claim

That’s a big claim, but Greenblatt seems to realize it may be too big. So, near the end of the preface, he writes:

“There is no single explanation for the emergence of the Renaissance and the release of forces that had shaped our own world. But I have tried in this book to tell a little known but exemplary Renaissance story, the story of Poggio Bracciolini’s recovery of On the Nature of Things.”

Greenblatt makes the point that the recovery of the poem was itself a kind of re-birth or renaissance of antiquity, something of metaphor for the Renaissance. And he adds:

“One poem by itself was certainly not responsible for an entire intellectual, moral, and social transformation — no single work was, let alone one that for centuries could not without danger be spoken about freely in public.

“But this particular ancient book, suddenly returning to view, made a difference.”

“Incomprehensible, unbelievable, or impious”

The Swerve is a book written for the general reader, and, in his 262 pages of text, Greenblatt covers a lot of ground in terms of history (about 1,500 years), literature (from Virgil to Shakespeare) and geography (Greece to Rome to Germany and England).

He also devotes twelve pages to a detailed examination of 20 elements of the Epicurean philosophy as it is expressed by Lucretius in On the Nature of Things. These flew in the face of the way Europeans (which is to say, European Christians) understood the world, life and meaning at the time Poggio Bracciolini rediscovered the poem in January, 1417.

Greenblatt points out that “many of the work’s arguments are among the foundations on which modern life has been constructed,” but he acknowledges:

“It is worth remembering that some of the arguments remain alien and that others are hotly contested, often by those who gladly avail themselves to the scientific advances they helped to spawn.

“And to all but a few of Poggio’s contemporaries, most of what Lucretius claimed, albeit in a poem of startling, seductive beauty, seemed incomprehensible, unbelievable, or impious.”

Two life stories

Greenblatt’s book is a biography of On the Nature of Things. Or maybe, better said, it’s a dual biography.

It’s the life story of the poem, constructed mainly through describing the world in which it was created and the position of Epicureanism as one of many philosophical schools in that world, and of its death, which is to say its disappearance due to anti-pagan efforts by Christians and shifting intellectual fashions.

The poem’s second life came when Bracciolini found it in the library of a German monastery, had it copied and, eventually, shared it with the world. Its ideas quickly spread in an often underground manner to the cutting-edge thinkers of an era that was ready to hear and consider and, in some cases, adopt them.

The Swerve is rich with anecdote and clear-eyed descriptions of people, places, events and ideas.

In my reading, I felt that Greenblatt went too far in painting the Christian impact on Europe in the darkest terms possible. The world of Thomas Aquinas and Chaucer, Beowulf and the Chartres Cathedral wasn’t as Philistine as he portrays. I suspect this black/white approach for communicating the differences between Christianity and Epicureanism was chosen in order to make his book more accessible to the general audience.

That said, The Swerve is a rich reading experience which makes philosophy and literary analysis not only interesting for the curious non-experts but also fascinating and even fun.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.4.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.