The claustrophobic story told by Victor Maskell — a gay, aristocratic Irishman, Cambridge Marxist, international Poussin expert, Russian spy and Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, nicknamed Boots by the Queen — is particularly cramped and airless,

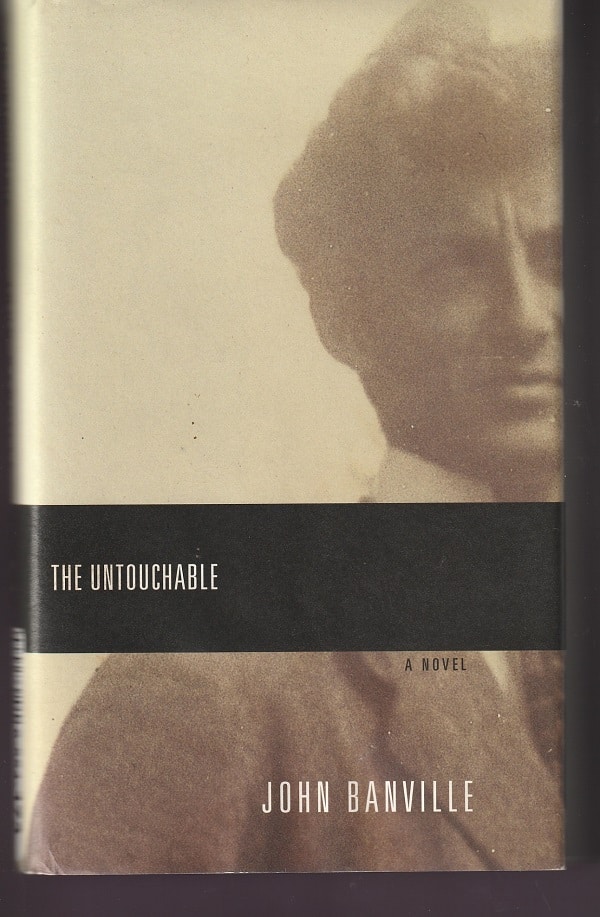

For one thing, as his story unfolds in John Banville’s 1997 novel The Untouchable, Maskell describes his deep entrenchment in the sort of well-insulated, self-satisfied, hedonistic life that was available to upper-class Britons throughout much of the twentieth century.

For Maskell and his circle — he was a member of the circle, not the central figure by any means — this was a life, as he details it, often spent drinking or drunk. It was a closed-in life among a coterie of friends, lovers, acquaintances and enemies.

Among people known by such names as Boy and Baby and Beaver and Big Beaver.

“Margins of my life”

Once, fairly late, Maskell discovered his homosexuality, he spent a good amount of his time among the lower classes, trolling for sex, but these lovers, even the one he sort of loved and did live with for a time, were always figures on the outskirts of his world. Visitors, like the plumber come to fix a leak.

Whether a lover or a maid or the driver of a military Jeep, anyone from the lower classes didn’t have much substance for Maskell.

Indeed, he describes them at one point as “nebulous figures milling restlessly, unappeasable, on the margins of my life.”

“Just for amusement”

The tight little world of Maskell and his circle was even more constricted because a goodly number of the men, Marxists from their university days, were double agents, working for the British intelligence service during World War II while also working as spies for the Russians before, during and after the war.

In a kind of rambling journal or memoir, Maskell talks breezily about betraying his nation’s secrets and about identifying British and allied agents in the Soviet Union, knowing the fatal consequences for those he fingered.

He describes himself as a Marxist awaiting a better world, but he shows great relish living in his world as it is, with its fine food, fine drink and fine art. When two of his fellow agents defect to Russia, he stays behind rather than lose the ability to visit the great art museums of the West.

Perhaps such a story told by one of the other double agents would have indicated a flame of idealism at the heart of the betrayals. There’s nothing like that, though, in Maskell’s narrative. Indeed, a fellow spy tells him at one point:

“You weren’t serious; you were just in it for amusement, and something you could pretend to believe in.”

Most stifling insularity

Maskell is a character who has no values, nothing he believes in, except maybe art. Even there, though, he sees himself more as the creator of the artist Nicholas Poussin than as a commentator about him. Maskell’s career’s worth of teaching and writing about the painter is what, in Maskell’s mind, has made the painter’s reputation.

Poussin is, in Maskell’s view, the creation of Maskell.

In art, in spying, Maskell isn’t outer-directed. He doesn’t see himself fitting into the wider world. That’s not where he goes for meaning. His world revolves around him.

This deep self-focus, a cluelessness about the life that anyone else lives, gives The Untouchable its deepest, most stifling insularity.

Untouched, untouched, untouched

The title, it seems apparent to me, is best taken as a reference to Maskell. Not only is he able to avoid prosecution for his spying when it is discovered, but it is also kept quiet and he is able to go on with his life as an art expert and respected scholar and friend of the royal family, including the new Queen to whom he refers as Mrs. W. (i.e., Mrs. Windsor).

He is untouched by scandal until late in life, and, even then, his notoriety seems to have relatively little impact on his life. He’s untouched by it, pretty much.

Then again, The Untouchable is a novel about how Maskell is untouched by the men and woman and children — including his wife and son and daughter, and his lovers, and his father and doting step-mother and developmentally disabled brother — and by essentially any elements of what most people would call real life.

Untouched by scandal, untouched by ties of love, untouched by the nitty-gritty of life, that’s Victor Maskell. And, in the end, he is astonished to discover that other people have lived full lives without his even knowing.

Patrick T. Reardon

12.2.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.