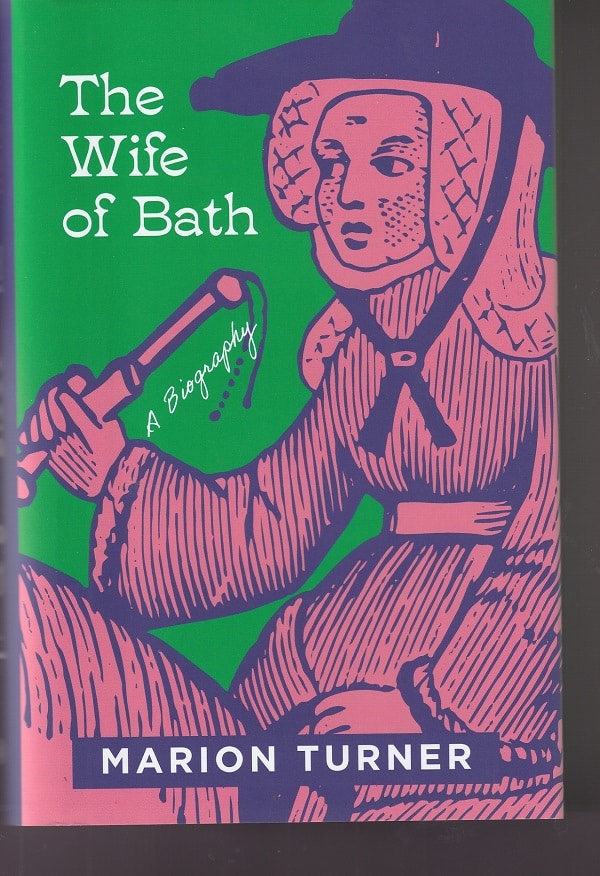

Two-thirds of the way through her insightful and thought-provoking new book The Wife of Bath: A Biography (Princeton University Press, 336 pages, $29.95), English literature scholar Marion Turner is writing about Shakespeare’s Falstaff.

The attractively comic knight — a major character in the plays Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; and The Merry Wives of Windsor — was rooted in part in the swaggering, self-important, corrupt soldier that was a stock figure for playwrights going back to the ancient Greeks and Aristophanes.

But, even more, Falstaff was inspired by Alison, the Wife of Bath, from Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, composed two centuries earlier, as Turner notes:

In particular, [Falstaff’s] profound confessional self-awareness and understanding of temporality, his appealing and persistent vitality, his use of the Bible, and his extreme verbal dexterity all link him to Alison. Ultimately, Harold Bloom was right to term Falstaff the Wife of Bath’s “only child.”

Shakespeare not only borrowed (and gave a gender change to) the robust, self-assured, zestful Wife of Bath but also adapted her Canterbury tale for The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Imagine a text. It is about middle-aged, economically competent married women who bond with each other to trick men, punish male cruelty, and mock male jealousy, while themselves maintaining their marriage vows. The text goes on to deal with the issue of educating men to think better of women and, specifically, to teach a knight [in Merry Wives, it’s Falstaff] that women are not necessarily sexually available to him. It is a text that sets women against knights and shows women winning….

Which text am I describing? Everything about that description fits both The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

“Fry in his own grease”

So, the Wife of Bath influenced Shakespeare’s creation of Falstaff, and her prologue and tale influenced Shakespeare’s play. And, beyond that, she also influenced the Bard’s language, as Turner points out.

In the Wife of Bath’s prologue, Alison tells of flirting with men to irritate her fifth husband — “in his owene grece I made hym frye/For angre, and for verray jalousie” (“I made him fry in his own grease till he/Was quite consumed with angry jealousy,” from a modern English translation by Ronald L. Ecker and Eugene J. Crook).

Frying in one’s own grease is quite an image, and it’s a rare one, found by Turner only in a minor poem by a contemporary follower of Chaucer — and in Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor.

In that comedy, Falstaff has propositioned two of the wives, and one of them, Mistress Alice Ford, suggests a way to get back at him — by leading the haughty knight on:

What tempest, I trow,

threw this whale, with so many tuns of oil in his

belly, ashore at Windsor? How shall I be revenged

on him? I think the best way were to entertain him

with hope, till the wicked fire of lust have melted

him in his own grease.

“The first ordinary woman”

Turner, who published Chaucer: A European Life in 2019,sets out now to tell the biography of Alison, the father of English poetry’s greatest creation, the Canterbury pilgrim who stands head and shoulders above the others in the Tales and the only one to continue to live on in other works of literature over the next six centuries.

The Wife of Bath is the first ordinary woman in English literature. By that I mean the first mercantile, working, sexually active woman — not a virginal princess or queen, not a nun, witch, or sorceress, not a damsel in distress nor a functional servant character, not an allegory.

Chaucer’s fictional character seems startlingly real with her bold speech and her prologue about life as a much-married woman and now as a widow “who works in the cloth trade and tells us about her friends, her tricks, her experience of domestic abuse, her long career combatting misogyny, her reflections on the aging process, and her enjoyment of sex.”

Before Chaucer, there hadn’t been characters like Alison in world literature, people from everyday life who talked about their feelings and experiences and personal histories.

The fact that Chaucer developed this kind of literary narrator in the form of a confident, well-off mercantile woman who tells jokes, enjoys sex, and thinks for herself about the male canon and the exclusion of women’s voices from it is astounding.

Astounding

Indeed, as The Wife of Bath: A Biography makes clear, there is much about the Wife of Bath that is astounding.

First, the simple fact that — in a literary canon that, for millenniums, had not only ignored women but tended to denigrate them — the Wife of Bath suddenly appears, larger than life, to make the case for herself and for all women.

She does this by simply being herself with all her “vitality, wit, and rebellious self-confidence” and also by making trenchant criticisms of some of the worst of the popular misogynist writings her time. And by telling a tale in which women gain the upper hand and men are taught a lesson.

It’s quite astonishing, as Alison makes a case for women in a world where such arguments had never before been in print and does so by raising the wide literature of anti-female texts and rebutting them one after the other.

“A mind unfolding”

It’s also astounding that the Wife of Bath was created by a man, Chaucer, well-rooted in the literary world that was casually and deeply misogynistic.

Yet, beyond simply communicating Alison’s story, Chaucer is able to do what great writers have done ever since — to put the reader inside the head of the Wife of Bath. He, though, is the first to do it.

As Turner notes, he gives the reader the sense that “we are seeing a mind unfolding” and enables the reader to “create Alison as a character as we enter into the illusion of interiority.”

After Alison details her wretchedness with the last two of her husbands, she says, “Who wolde wene, or who wolde suppose,/The wo that in myn herte was, and pyne?” (“Who could have thought, who would suppose/The woe and torment that was in my heart?)

Again, Chaucer creates the illusion of depth, telling us that there are things going on beneath the textual surface, encouraging us to “wene” and “suppose” — that is, to think about, imagine — how she feels, as if she is a real person.

“Alison’s reach, influence, and capacity for reincarnation”

The Wife of Bath is astounding in two other ways, the first being her long life in the writings of many others over the six centuries after Chaucer created her.

The Wife of Bath is one of only a handful of literary characters — others include Odysseus, Dido, Penelope, and King Arthur — whose life has continued far beyond their earliest textual appearances.

I can think of no other examples of this kind of character — a socially middling woman — who has had anything like Alison’s reach, influence, and capacity for reincarnation.

After her appearance in The Canterbury Tales, Alison showed up again in Chaucer’s other writings and then was seized upon by later generations of readers, novelists, poets and playwrights.

Over and over again, in different time periods and cultural contexts, readers see her as “relatable” in certain ways, as a three-dimensional figure who is far more than the sum of her parts. She may be “ordinary,” but she is also extraordinary.

“Feared, hated, mocked, ridiculed”

Finally, it is astounding that, in Alison’s life after The Canterbury Tales, she has often been reviled or refashioned or revised in misogynistic ways to make her more socially acceptable, i.e., less real and less original and, well, less threatening.

When examining her adventures across time, it is striking that this is not a story of decreasing misogyny. Many twentieth-century responses, which often focused on her body and her sexual appetites in an extreme and caricatured way, were more misogynistic than fifteenth-century engagements with Alison, which were often more concerned with combating her rhetorical power.

Turner writes that, for many readers and rewriters including Dryden, Voltaire and even the scribes who were copying Chaucer’s poem and felt the need to add catty criticisms in the margins, “Alison has been a figure to be feared, hated, mocked, ridiculed, and firmly put in her place.”

“A magnetic pull across time”

Nonetheless, the Wife of Bath has not only survived such attacks but has thrived and continues to do so because of the alchemy of Chaucer to bring the reader inside this bold, brassy and zest-filled fictional human being.

Alison is unique, a literary character like no other who exerts a magnetic pull on readers and writers across time.

Where else could authors turn if they want to find a dramatic, interesting, larger-than-life, yet accessible, female character with instant recognizability and a long literary history in English?

The Wife of Bath, writes Turner, is an extraordinarily rich source of inspiration as “a figure who blurs the boundaries between extreme stereotype and mundane everywoman, and who is at once a funny performer, a defender of women’s rights to speak and not to be abused, a skilled orator, a self-avowed liar, and font of knowledge and self-knowledge.”

In sum, for more than six centuries, the Wife of Bath has been and continues to be quite an astounding fictional human being.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.17.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.