Sometime last September, I happened upon a musical called The Wild Party — book, music and lyrics by Andrew Lippa — being performed by the Blank Theatre Company on a small commercial street on the Far North Side of Chicago.

It was a fun show, a muscular and frenetic melodrama, set in a 1920s New York City apartment, dripping with sex and scandal, heavy drinking and violence.

The subject — songstress Queenie and her live-in lover Burrs are at odds and decide to have a wild party as a way to revive their low spirits — could be seen as an invitation to campiness. But the Blank Theatre cast embraced the tale in its fulness, playing the seedy and transgressive story with a lively relish.

The play was based on a book-length poem The Wild Party by Joseph Moncure March that was so hot and bothered it was published quietly in 1928 — and still got banned in Boston.

“Not like today, it’s all okay, ole, ole”

My enjoyment of the show prompted me to track down a copy of the poem in a 1994 edition, published with an introduction and a host of tri-tone drawings by Art Spiegelman. It too avoided campiness, and I thought of the Peter Allen song “Paris at 21” from his 1979 album I Could Have Been a Sailor.

It’s a delightfully melancholy song of an innocence lost — the ability to be a 21-year-old in Paris in 1921 — and Allen makes his point early on with these key lines:

Would have been there

But I wasn’t born

Would have had the time of my life

Would have sinned there

‘Cause that’s when sin

Was cheating on your wife

Not like today, it’s all okay, ole, ole

“Perfectly pitched tone of bewildered innocence”

That, it seems to me, is why Lippa and the Blank Theatre group didn’t go for a lot of nods and winks and suggestions about how quaint those silly people were a century ago — “Can you imagine them believing that they were scandalous (and, yes, sinful) for living a life of casual sex and heavy drinking and partner-trading and casual nudity with gay people and mixed-race people, low and high?”

Lippa et al told the story straight, presenting all of what the characters saw as sinning as, in fact, for them, sinning. Spiegelman does the same, as he explains in his introduction:

My own desire to illustrate The Wild Party grows from something beyond a yen for the innocent hedonism of a boop-a-doop and vo-de-oh-do twenties, although I confess to a powerful nostalgia for all decades that preceded my birth….

Maybe it’s March’s perfectly pitched tone of bewildered innocence curdled into worldly cynicism that resonates so well [today].

“The fiercest, cleanest love”

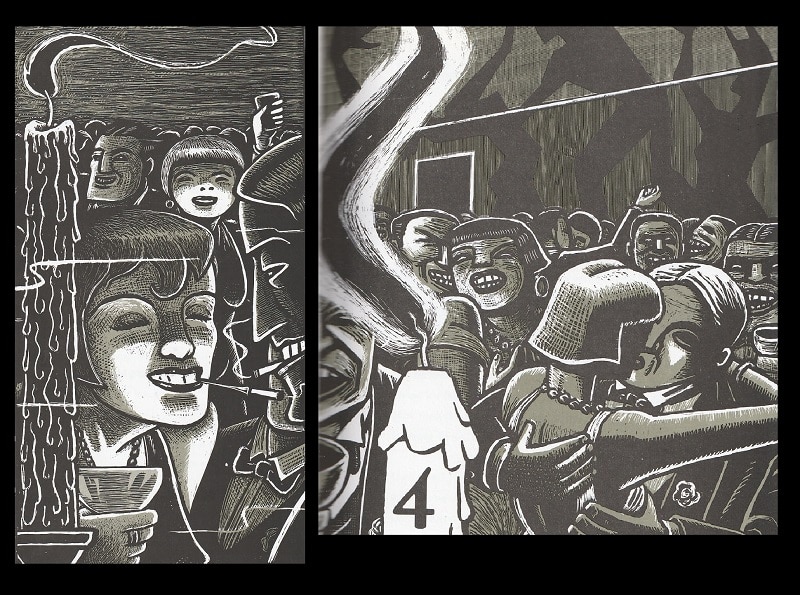

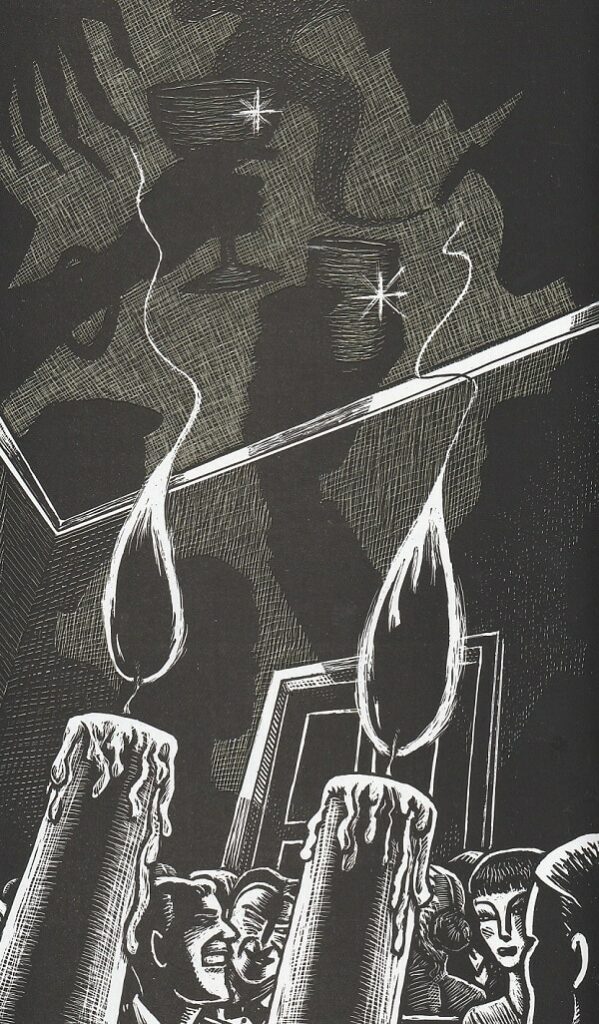

In Spiegelman’s drawings, Queenie spends much of the book naked, all the way to the end when one lover is dead and another is about to be arrested.

This fits the emotional edginess of the story and Queenie’s role in it, summed up in one of the final pages when she and a new man are getting it on in the bedroom:

Some love is fire; some love is rust;

But the fiercest, cleanest love is lust.

And their lust was tremendous. It had the feel

Of hammers clanging; and stone; and steel….

And so on.

Okay

I found even more compelling the several images in which Spiegelman captured the claustrophobic and frenzied party itself.

Not like today, it’s all okay, ole, ole.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.12.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.