When 27-year-old Juliette Kinzie settled with her husband John, the local Indian agent, in the tiny hamlet of Chicago in 1833, it was the home of only about 300 people, several of them Kinzie relatives. Nearly three decades later, when she left, shortly before her death, the population had boomed to some 300,000.

She watched Chicago grow from a scattering of small buildings to an expansive and expanding railroad and industrial center set in a rigid street grid, and, through her involvement in creating the civic culture, she helped shape the nascent city.

Indeed, as Chicago’s first historian, she chronicled its early years in her 1856 book Wau-Bun: The ‘Early Day’ in the North-West and in an earlier book Narrative of the Massacre at Chicago, about the Battle of Fort Dearborn in the War of 1812.

When, later in life, she described her husband and herself as “grandfather and grandmother of Chicago,” it was an overstatement, but not completely inaccurate.

The woman who lived that life

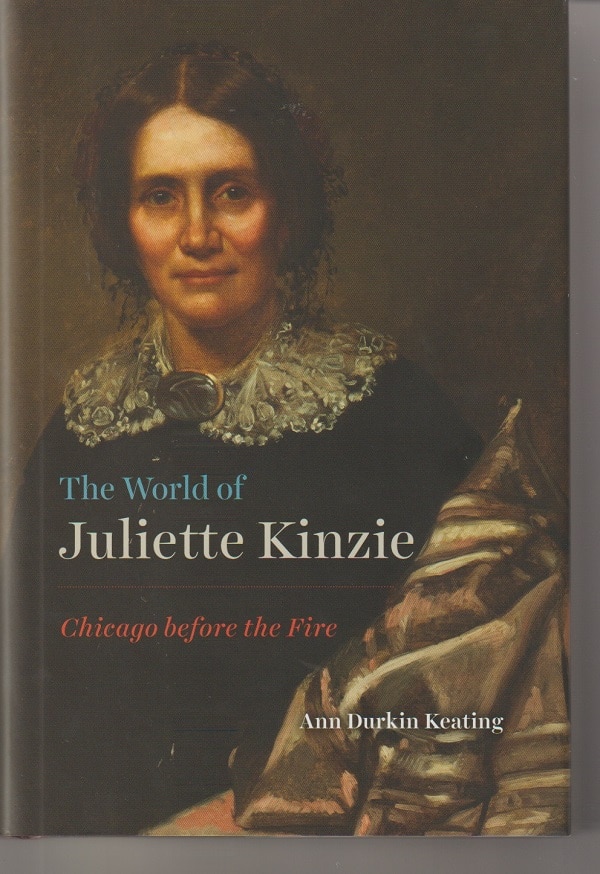

The basic facts of Juliette Kinzie’s life have long been known but not the woman who lived that life. Ann Durkin Keating’s brisk, sensitive and scholarly biography The World of Juliette Kinzie: Chicago before the Fire remedies that.

As the title suggests, Keating’s book isn’t so much a “life and times” account, but a tale of Chicago and its people through the feelings and experiences of Juliette Kinzie and her household.

Households, the book shows, were a key factor in young Chicago before the local and national culture shifted to a greater emphasis on the individual. Juliette’s husband John took part in the creation of the society, institutions and ethos of the new city as a representative of his household.

In fact, many of the meetings at which such questions were discussed, such as the founding of the Chicago Historical Society, were held in homes and attended by women as well as men.

Alongside servants

It was an era when the mistress of a household was as much as worker as those who worked for her, as Keating explains:

“Juliette expected a great deal from servants. She worked long hours alongside them, keeping clothing, cookware, carpets, and curtains clean. Together they whitewashed the house, the interior walls, and the fences.

“In one of her novels, Juliette described a household in the midst of a ‘Dutch cleaning’ with ‘carpets hanging upon the fences, chairs, tables, and sofas filling the piazza, or even, for want of room upon the roof, blankets and woolen garments sunning in the open windows.’ Inside two servants were scrubbing parlors, and another was whitewashing the dining room.”

“You belong to him”

In her book, Keating provides a full-bodied, 360-degree portrait of Juliette and her household by mining a deep vein of the woman’s own words — not only in her two history books and two novels but, even more, in an immensely rich archive of some 500 letters that she exchanged with her daughter Nellie Gordon in Savanah, Ga., before, during and after the Civil War. (Nellie’s daughter, also named Juliette, was the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA.)

In her book, Keating provides a full-bodied, 360-degree portrait of Juliette and her household by mining a deep vein of the woman’s own words — not only in her two history books and two novels but, even more, in an immensely rich archive of some 500 letters that she exchanged with her daughter Nellie Gordon in Savanah, Ga., before, during and after the Civil War. (Nellie’s daughter, also named Juliette, was the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA.)

Keating’s 2012 book “Rising Up from Indian Country: The Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago” relies on Juliette’s history for eyewitness accounts of the fighting but disputes her characterization of the attack as a massacre rather than a military action of war.

Similarly, in “The World of Juliette Kinzie,” Keating is not comfortable with some aspects of her subject, such as Juliette’s firm belief in the hierarchical nature of a household, with the husband firmly at the top. Indeed, when Nellie complained about her husband, Juliette admonished:

“You belong to him…You must remember that as an individual you have ceased to exist, being part and parcel of Mr. William Gordon.”

Neither does Keating endorse Juliette’s prejudices against African-Americans and Irish immigrants. Yet, she recognizes that her subject lived in an era when efforts for gender and racial equality were still in the early stages.

Of her time

Keating’s book captures a woman of her time who is also an individual. Juliette Kinzie is a representative of women, wives and mothers in mid-19th century America, sharing the beliefs and prejudices of many. But she had her own quirks — she was a writer and historian in a time when few women were published — and her own joys and sorrows.

It’s sad that, after her husband died, Juliette spent much of her final years trying to make ends meet and shepherding financial settlements through the courts. It’s also particularly sad that she and her husband died on trips away from Chicago.

Juliette’s is a Chicago story. And it’s also her story.

Patrick T. Reardon

2.xxx.20

This review appeared originally at Third Coast Review on 1.9.20.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.