For Thomas R. Nevin, the key insight into the short life and rich spirituality of Thérèse of Lisieux is to be found in a conversation in January, 1897, eight months before her death from tuberculosis.

Thérèse, a Discalced Carmelite, known in her French convent as Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, was designated a Roman Catholic saint nearly a century ago. She is popularly venerated as The Little Flower of Jesus and is often pictured in statues and holy cards tranquilly holding a bouquet of roses, clustered around a crucifix.

In its outlines, the life of Thérèse can appear serene. She was the lively, doted-upon last child in a happy and devout family. All five of the daughters, the only offspring to survive childhood, became nuns. Thérèse entered the Lisieux Carmel at the age of 14, joining two of her sisters and later welcoming a third. She died a decade later, leaving behind three manuscripts, published as The Story of a Soul, one of the great religious documents of Catholicism. At the end of the 20th century, Pope John Paul II declared her a Doctor of the Church, one of just 36 saints so designated, only four of them women.

In Thérèse of Lisieux: God’s Gentle Warrior, Nevin makes it clear that Thérèse’s life was far from tranquil, as her 1897 conversation with another nun revealed.

Sister Thérèse Saint-Augustin told the dying woman she’d had a dream in which Thérèse was in a very dark room, getting herself ready to join her magnificently dressed father and go through “an extremely black” door to a world of only light.

She was, most likely, thinking of the dream as a message of consolation that Thérèse would soon accompany her late father into heaven. But, in what Nevin calls “a dumbfounding response,” Thérèse replied:

“I don’t believe in eternal life. It seems to me that after this mortal life there’s nothing more. I can’t tell you of the shadows in which I’m plunged. What you are telling me is precisely the state of my soul. The preparation I’m supposed to make and especially the dark door is the very image of what’s happening in my soul.”

The door, which the dreamer had imagined was a way into heaven, was, for Thérèse, “grim” and a sign that

“everything has disappeared for me and I’m left with only love.”

“My shadows even thicker”

This is an astonishing statement, especially for a woman declared a saint and a Doctor of the Church, a church whose teaching is based on faith, hope and love.

Nevin asserts, based on a nuanced reading of The Story of a Soul as well as a wealth of other sources, that Thérèse’s spirituality had no expectation of a payoff for being good, for following God’s rules — no expectation of heaven. (Or, for that matter, hell or purgatory.)

As her words to Sister Saint-Augustin indicated, Thérèse had come, at this moment shortly after her 24th and final birthday, to an understanding that all she had was her present life. She did not believe or hope in a life after death.

She was “left with only love,” love of God, love of other people — and she was content with that.

Indeed, in all of Thérèse’s writings, she used the word “faith” 57 times and “hope” 38 times. The word “love,” though, appeared in 756 places.

Five months later, in the third installment of what became her autobiography, Manuscript C, she wrote:

“When I sing the happiness of Heaven, the eternal possession of God, I feel no joy in it. In fact, I’m simply singing what I want to believe. Sometimes, it’s true, a little ray of sun comes to enlighten my shadows and then the testing stops for a moment, but then the memory of that ray instead of causing me joy makes my shadows even thicker.”

In other words, the recollection that, for a moment, she’d had this “little ray of sun,” of hope, is no solace. Instead, it is a kind of taunting, an even deeper reminder of what she does not have and cannot claim, and makes her darkness even darker. Nevin writes:

“She seems oblivious to the cue of hope which the dream narrative was affording…It seems that by the mid-winter of 1897, she had passed beyond all likely or even possible retrieval of faith and hope in a celestial life.”

“Her equanimity”

Nevin writes that wanting to believe isn’t the same as believing. Thérèse had lived a life based on abandon, the French word for surrender, to love. She remained deeply in this surrender to love, without any joy of heaven. Nevin writes:

“Once she accepted that her inherited and unreflected notion called heaven was a void, she let it drop.

“Her equanimity in this central matter of faith and hope can only amaze believers and nonbelievers alike because she did not attempt to contrive or imagine some other realm. When she told Saint-Augustin she did not believe in heaven, she was not in despair nor in hysterics. She had learned to read God’s testing of her.

“She could go on loving God even if all thought of heaven and its delights were taken from her.”

Even though she continued to live in spiritual darkness. And to suffer the great pains of her illness.

“The aversion Thérèse felt”

The pain of that darkness and of that illness was part and parcel to the life Thérèse had fashioned a life for herself — a life based on suffering.

Non-Christians and certainly many Christians will find this idea unfathomable and write it off as a version of masochism. Yet, Christianity, as a religion, has as its central image a scourged, nailed man, dying on a cross, an instrument of execution akin to the guillotine and the electric chair. Suffering was central to Thérèse’s spirituality, so central that, even before her darkness descended so thoroughly, “the thought of heaven was troubling because she could not imagine a state without suffering and without solicitation for the needy.”

Love of God, for her, involved accepting open-armed — embracing — the pain of life as a form of divine testing of love. Anything that was irritating or agonizing or distressful was, for her, an offering from God to deepen her love.

One minor example, states Nevin, is Sister Saint-Augustin, the nun of the January, 1897 conversation, a nun whom Thérèse “so detested that she could hardly bear to be near her.” Nevin writes:

“On occasion, Thérèse had to rush suddenly away from her in order to arrest an outburst. At other times, she would force a kindly smile, a tactic that explains why Sister Saint-Augustin never suspected the aversion Thérèse felt for her.”

Not only that, but, in attempting to treat the pushy Sister Saint-Augustin charitably, Thérèse agreed to her request to write a religious poem for her and thus began her writing career.

And it was to this off-putting nun that Thérèse revealed the deepest depths of her darkness.

Suffering “does not lie”

Nevin points out that, for John Donne and many other earlier spiritual writers, suffering “has supreme value because it does not lie and bids the sufferer not to either.” But it meant much more for Thérèse:

“It is necessary to suffer, to agonize….As for me I’ve believed that one must not suffer pettily or wretchedly.”

To which, Nevin adds:

“Only a grand, brave, and generous scale of suffering would do. That notion jibed with her insistence that one cannot be a saint by half.”

“Perfect Love”

Nevin writes on his first page that Thérèse of Lisieux: God’s Gentle Warrior is not a hagiography, i.e., that it is not the story of a saint told in a way to inspire the religious feelings and understanding of believers.

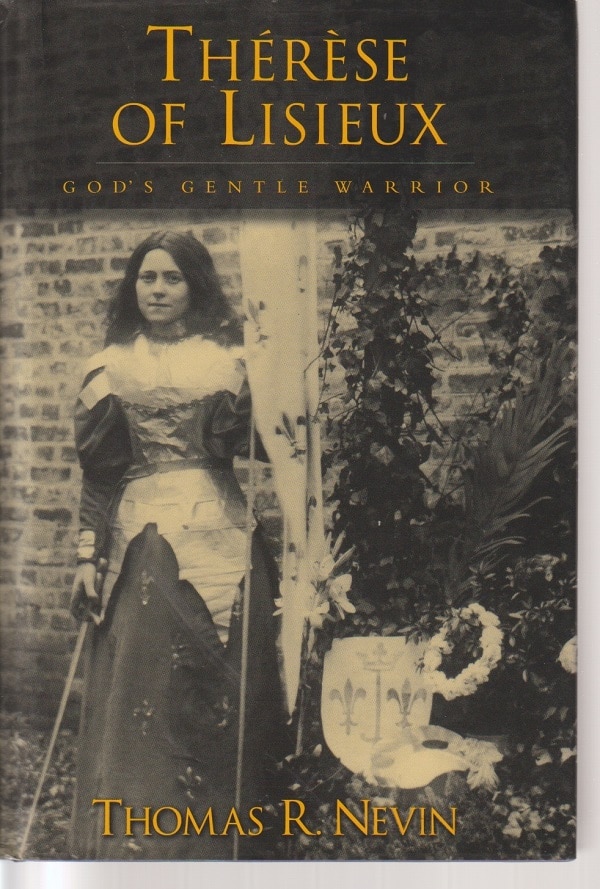

Thérèse in costume as St. Joan of Arc for a play she wrote and performed for the nuns in her convent.

His book is a deeply respectful biography of a major religious figure which aims to place her in her cultural setting and, therefore, better trace the roots of her understanding of God’s relationship to humanity — and to wrestle with the hard questions and, at times, uncomfortable implications of her spirituality.

Thérèse of Lisieux: God’s Gentle Warrior is an unusual and challenging book, elegantly written and dealing with complex, freighted and weighty religious issues. It confronts Thérèse boldly and courageously as she confronted her life and God with open arms and heart, with deep feeling and with great verve.

This is a biography told in nine essays, one of which, the second, gives a quick, 44-page chronological sketch of her life. Thérèse’s was lived within the context of French Catholic thought, her mother’s beliefs and sufferings, and the spirituality of the Discalced Carmelites going back three centuries to their founder, another towering religious figure, Doctor of the Church and author of another great religious classic, St. Teresa of Avila. Nevin devotes a chapter to each of these three.

Having provided this perspective, Nevin offers chapters that look at Thérèse as a writer about herself, as a poet and playwright and as someone suffering tuberculosis. Then comes the core of the book, the eighth chapter, “Perfecta Caritas: Notes on a Theology of Thérèse,” followed by a short open-ended ninth chapter, “Inconclusions.”

The table of sinners

In the final years of her life, Thérèse lived within a fog of darkness, and Nevin writes that she “learned within her fog to consider spiritual strays as her kindred.” In fact, in a prayer to Jesus, she described herself as the sister of such strays, asserting:

“she asks of you forgiveness for her brothers, she agrees to eat for as long as you wish the bread of grief and she does not wish to rise from this table of bitterness where the poor sinners eat before the day you have appointed.”

Consider this well. Although eating the “bread of grief,” Thérèse wants to remain at “this table of bitterness,” the table of sinners.

Suffering was not something to be simply endured. Thérèse recognized that her darkness — her feeling of separation from God — was also felt by anyone without faith or hope. And she welcomed her membership at their table.

“Remain in the shadows”

In this way, she faced suffering with love of God — and with love of others, particularly sinners, particularly those who saw the present life as a dead end. Nevin writes:

“Convinced that the darkness was God’s work, that it had been appointed for her to suffer, she could affirm it. The [500-year-old devotional book The Imitation of Christ] told her that all she was suffering, Christ was suffering with her, and if she could find that suffering sweet and love it for Christ’s sake, she would find paradise on earth.”

This, however, would not be a pain-free paradise. The blissful elements would be in the suffering itself. She wrote in a poem:

“When the blue Heaven darkens and seems to desert me, my joy is to remain in the shadows….I love the night as much as the day.”

To which, Nevin adds:

“It remains a fearsome fact that Thérèse learned to welcome the void of faith and of hope. It is as well an indigestible fact.”

And further:

“Now, she knew herself desolate and impotent, delivered to an absurd darkness, keeping company with the desperate. She had used the old trope of the Carmel as a prison but now she was truly imprisoned. Strangely, in the midst of this torment, there was also peace.

“Her composure came from knowing experientially that, stripped of faith and hope, she could now be overwhelmed by God. Reduced to this bottom-line nothingness, her vision could not be clearer. Most important of all, from this vantage, with all desires gone save to love Jesus, that love was the purest possible.”

“Extreme and improbable”

Thérèse, Nevin writes, was “an extreme and improbable person” who, young and dying, “fashioned a revolutionary ethic of love, one which subtracted, in part by neglect and in part by experience, the tenets of faith and the self-absorbing illusions of hope.”

In this way, she belies the assertion of nonbelievers that self-interest is at the heart of Christianity — the trading of this world for a payoff in heaven or, as George Orwell said, “the Christian bribe.”

Theologian Simone Weil once asserted that the power of Christianity was that it put suffering to transcendent use, and that, according to Nevin is what Thérèse “did with her darkness, the vault and the fog.” He continues:

“By anyone’s estimate, her example should stand as a tribute to human tenacity and resourcefulness against apparently insuperable odds. A Christian could and should maintain that it was by grace itself that she went on. Thérèse herself would have agreed.”

“Saint of the hopeless”

Sitting at the table of sinners, Thérèse “becomes the saint of the dispossessed, of all who sit in darkness, including those who care to gloat in it. At the same time, she speaks to those within the folds of faith who feel deeply troubled and bereft of hope, who find themselves lacking the warmth and sustenance of faith.” And he concludes:

“Thérèse is the saint of the hopeless, both within and without the Church. She is the saint of those who fear to acknowledge that their faith has been weakened or lost altogether.

“The roses and statuary remain for those to whom they are vital signs of the little way of little doings, but neither roses nor statuary belong in that testing darkness where both the fallen and the fallible are found. Which includes most of us.”

Patrick T. Reardon

8.7.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Thank you for this magnificent review—and for your companion review, equally penetrating and thoughtful, of Thomas Nevin’s sequel, “The Last Years of Saint Therese: Doubt and Darkness, 1895-1897.”

Thanks, David. I found both books deeply moving and deeply spiritual.