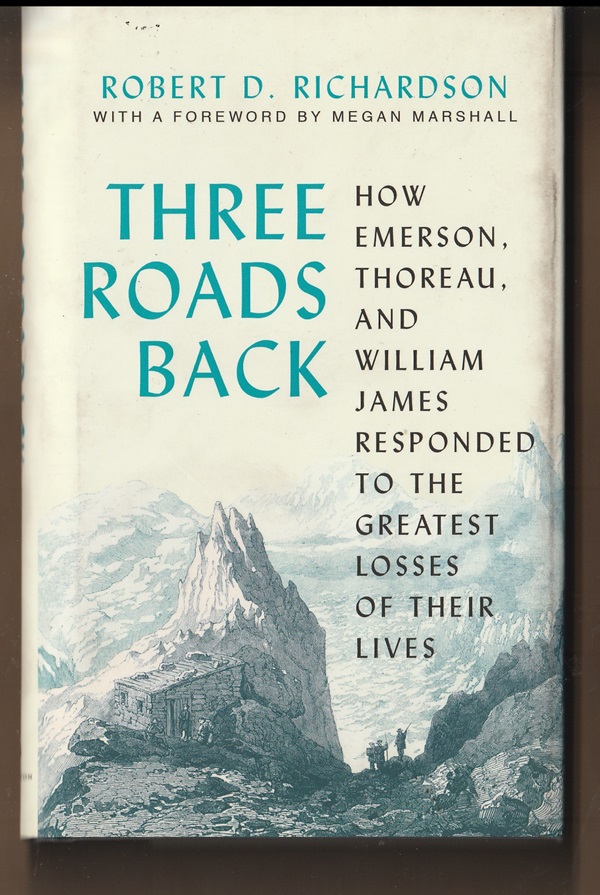

“Think of them as fellow human beings,” Robert D. Richardson instructs the reader in the preface of his 2023 book Three Roads Back.

And that is apt advice although, at least at the beginning, the reader may find it difficult to follow since the “they” Richardson writes of are three 19th century giants of American literature: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and William James.

The fact is, though, as Richardson notes, even famous, important, gifted people have to face “losses and troubles much like ours.”

Emerson, Thoreau and James were at the start of their lives when a close relative or friend died young. The grief was shattering, and each of the men was faced with the question of what to do with his deep sorrow.

“The affections cannot keep their youth”

Emerson’s 19-year-old wife Ellen died of tuberculosis on February 8, 1831. Emerson, a Unitarian minister, was 27, and, five days later, despite the orthodox Christian beliefs he then still held, he wrote in his journal:

But will the dead be restored to me? Will the eye that was closed on Tuesday ever beam again in the fulness of love for me? Shall I ever again be able to connect the face of outward nature, the mists of the morn, the stars of eve, the flowers, and all poetry, with the heart and life of an enchanting friend?

No. There is one birth, and one baptism, and one first love, and the affections cannot keep their youth any more than men.

“What do you want?”

Thoreau was 24 when his brother John, three years older, died of lockjaw on January 11, 1842. Then, sixteen days later, he was dealt a second great blow when Waldo, the five-year-old son of his close friend Emerson, died of scarlet fever.

A few weeks later, Emerson visited Thoreau, hoping, it seems, to bring consolation. But, Richardson reports, the younger man was “querulous, grouchy, self-critical,” writing in his journal:

It is vain to talk. What do you want? To bandy words — or deliver some grains of truth which stir within you? Will you make a pleasant rumbling sound after feasting for digestion’s sake? Or such music as the birds in springtime.

“In the tomb with you”

Mary Temple, known as Minnie, a cousin of William and Henry James, was 24 when she died of TB. She was, writes Richardson, “simply and without question the most interesting, most intelligent woman that William and Henry knew.”

William, who was 28 at the time and had already been deeply depressed for more than a year and a half, wrote two weeks later in his journal:

By that big part of me that’s in the tomb with you, may I realize and believe in the immediacy of death. Minnie, your death makes me feel the nothingness of all our egotistical fury.

“The ‘work’ of mourning”

Three Roads Back, a deeply felt, subtly nuanced work of just over 100 pages, was written at the end of Richardson’s career and life, and it’s rooted in the three magisterial biographies that made his name in American literary circles:

- Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind (1986)

- Emerson: The Mind on Fire (1996)

- William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism (2007)

When the book was still in manuscript, Richardson sent a copy to his friend Megan Marshall. At the time, Marshall, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for her 2013 biography of another 19th century literary figure, Margaret Fuller, was sorrowing over the death her life partner, poet Scott Harney, in May, 2019.

In a foreword to Richardson’s book, she writes that his manuscript was “the most extraordinary book on the ‘work’ of mourning I would come across during my season of grief.”

A year after Harney’s death, Richardson — who was married to Annie Dillard, the winner of the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for her non-fiction book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek — died after a fall in June, 2020, at the age of 86.

“In common with his subjects”

When he was writing Three Roads Back, Richardson had no way of knowing of his approaching death although, unlike young people, those in their 80s are well aware that the end of life isn’t too far away.

Marshall points out in her foreword that Richardson “had in common with his subjects an experience of early loss.” He was 21 when his younger brother John died of leukemia at the age of 17 in 1954.

Is it any wonder Bob’s first biography told the story of a writer who held his brother John in his arms as he died, convulsing, delirious, of lockjaw?

We need not ask how and when Bob Richardson learned resilience. And we know what it allowed him to do: write the enduring biographical works that are his legacy.

“Lasting contributions”

The manuscript that Richardson sent to Marshall in 2019 was titled simply Resilience. In his preface to Three Roads Back, he writes:

[Emerson, Thoreau and James] faced disaster, loss, and defeat, and their examples of resilience count among their lasting contributions to modern life.Emerson taught his readers self-reliance, which he understood to mean self-trust, not self-sufficiency. Thoreau taught his readers to look to Nature — to the green world — rather than to political party, country, family, or religion for guidance on how to live.

William James taught us to look to actual human experience, case by case, rather than to dogma or theory, and showed us how truth is not an abstract or absolute quality, but a process.

Richardson aims in his short book to show how these three luminaries lived through the process of mourning and then out of mourning into the rest of their years, to highlight them as examples of “how to recover from losses, how to get back up after being knocked down, how to construct prosperity out of the wreckage of disaster.”

A richer life out of sorrow

Don’t get the idea, though, that Three Roads Back is a how-to book. Richardson takes a tightly focused approach, based mainly in letters and journal entries, to examine the traumatic emotional blows the three writers suffered and the very personal ways in which they responded.

These losses were turning points for the writers. They sent the writers down paths that, because of their depth of intellect, sensitivity and openness, resulted in rich and important literary works over the rest of their lives.

Their responses to these losses don’t provide a blueprint for the reader on how to handle one’s own tragedies.

Yet, their responses show that a deepening and enrichment of living can result from profound sorrow — that a new, joyful time can be reached, not by denying the loss or seeking to forget it, but by incorporating the loss and the lost friend or family member into one’s future life.

An act of will

I’m not sure that “resilience” is the best word for this process.

It certainly works, as far as it goes. Emerson, Thoreau and James were resilient in how they bounced back or out of the depths of sorrow that they were in.

But it seems to me that there is something deeper. Resilience seems to be an ability that some may have and others not. This would mean that some people in mourning wouldn’t have the knack for it and would have no way to get out of their grieving.

I think this process — which I have gone through, particularly after the suicide of my younger brother David in 2015 — has more to do with will.

It seems to me that someone who has been driven to the depths of sorrow by the loss of a loved one has the choice of fully embracing the loss or turning aside from it. It’s an act of will.

Embracing the loss

Those who turn aside essentially leave the loss out of their lives and miss the opportunity to grow through the mourning process.

Those who embrace the loss for all its pain and emotional force are able, it seems to me, to incorporate it into the rest of their lives in a manner that makes those remaining years richer.

As James wrote, when one chooses to embrace the loss, one is better able to “realize and believe in the immediacy of death” — and, by the same token, to realize and believe in the immediacy of life, in the preciousness of each moment, in the wonder of every dawn.

Three Roads Back is a deeply rich book about finding life after sorrow. And you don’t have to be a literary genius to learn from it.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.27.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.