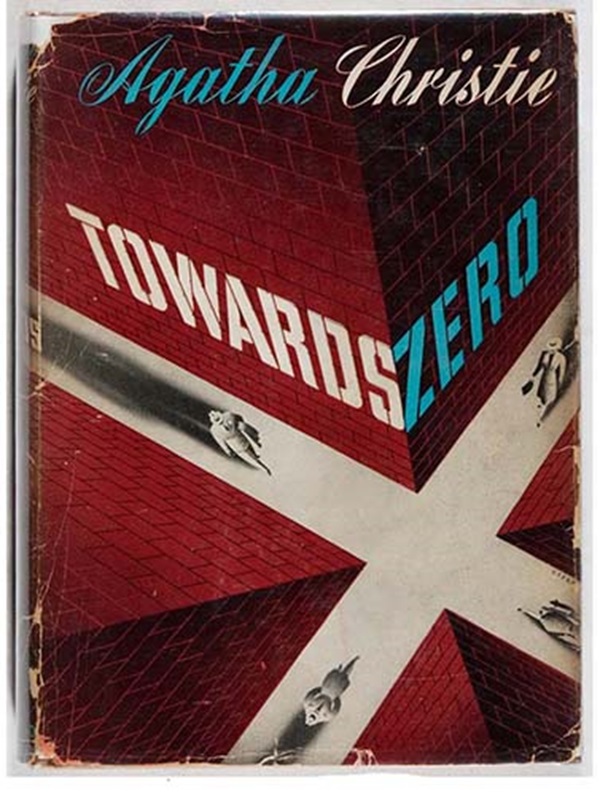

Towards Zero, published by Agatha Christie in 1944, is a reminder of how creative she was as a mystery writer.

Christie was the epitome of what’s called the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, the 1920s ands 1930s, when crime novels, especially those written by Britons, had similar plots and followed similar patterns.

The story would center on a small group of generally affluent people, such as those at a gathering for the weekend at a mansion. Early on, someone would be murdered and, a little later, someone else.

An idiosyncratic detective, usually an amateur, rarely an actual copper, would interview everyone and search for clues and, at a meeting of the group in the final pages, would identify the killer and the ways the killings were carried out.

It was a formula, and it resulted in a rich trove of books that were fun, in many ways, because they stuck to the formula. The interest was how, here or there, a story might deviate slightly from the recipe. Christie was an expert at such books and an exemplar of such writers.

Yet, she also knew how the blow the formula to kingdom come with such books as And Then There Were None (1939), The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) and Five Little Pigs (1942).

“Converging towards zero”

Towards Zero isn’t in their class, but it does twist and turn the formula more than a bit out of shape, even while following some aspects of the pattern.

Christie sets up her story and her story-telling approach with a Prologue in which Mr. Treves, a respected 80-year-old solicitor, tells a roomful of attorneys that detective stories always begin at the wrong place:

“They begin with the murder. But the murder is the end. The story begins long before that — years before sometimes — with all the causes and events that bring certain people to a certain place at a certain time on a certain day….

“All converging towards a given spot…And, then, when the time comes — over the top! Zero hour. Yes, all of them converging towards zero.”

And that’s how Christie proceeds.

An unusual chronological approach

The murder doesn’t occur until halfway through the book (unless you want to call the “accidental” death of one character, that occurs about a dozen pages earlier, a murder as you’re likely to want to do when you get to the end of the novel).

Over the course of a 36-page opening section, Christie employs an unusual (for her) chronological approach, counting down from January 11 while introducing her characters as they do things and make decisions that will bring them in early September to Gull’s Point, the mansion of Lady Camilla Tressilian, an aged and ailing and autocratic widow.

Lady Tressilian’s visitors include Nevile Strange and his two wives — well, of course, one is his present wife Kay and the other is his former wife Audrey.

Most of the others in the group think that Nevile, a Wimbledon tennis player known for his good sportsmanship, was tricked by Audrey into setting up the weekend, perhaps as a way for her to wreak vengeance on the woman who replaced her.

To put it mildly, the visit is filled with tension and an atmosphere of menace, so it is no surprise when, finally, the murder takes place.

Superintendent Battle

This is when Christie’s detective enters the story, but it’s neither of her most famous creations — Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple. Instead, it’s Superintendent Battle, a stolid, phlegmatic veteran detective.

She had used Battle to solve the crimes in two earlier novels: The Secret of Chimneys (1925) and The Seven Dials Mystery (1929). He had a small part in Murder Is Easy (1939) and was one of several detectives in Cards on the Table (1936), a mystery solved by Poirot.

Towards Zero is his last appearance in print, and she used him, I think, for several reasons.

First, it was another way of breaking with the formula to have a policeman solve the crime. Second, it broke with the formula in a different way to have Battle come up with the wrong solution to the crime. Third, Battle is anything but flamboyant, and that enabled Christie to keep the focus more tightly on her characters and their interactions with each other.

Fourth — and maybe most important — the solution to the crime that was finally provided by something of a bystander needed a nod and a wink from a police official, something Battle was able and willing to do.

Lying and pretending

There is a lot of lying and pretending in Towards Zero, for good and bad reasons. Although every mystery has its share of lying and pretending, there’s more than usual here. That makes possible a very nice, unexpected and probably unique twist at the very end of the book.

Nonetheless, Towards Zero is good Christie, not great Christie.

Delaying the murder until midway through the book and delaying the appearance of the detective until then (except for a few early pages) means that there is no central personality around which the story is told nor a central event that is the focus of everyone’s thinking. Also, there’s all that lying and pretending.

As a result, the first half of the book is less coherent than it might have been.

Even so, Towards Zero is worth a read. After all, good Christie is much better than the best of most other mystery writers.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.15.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.