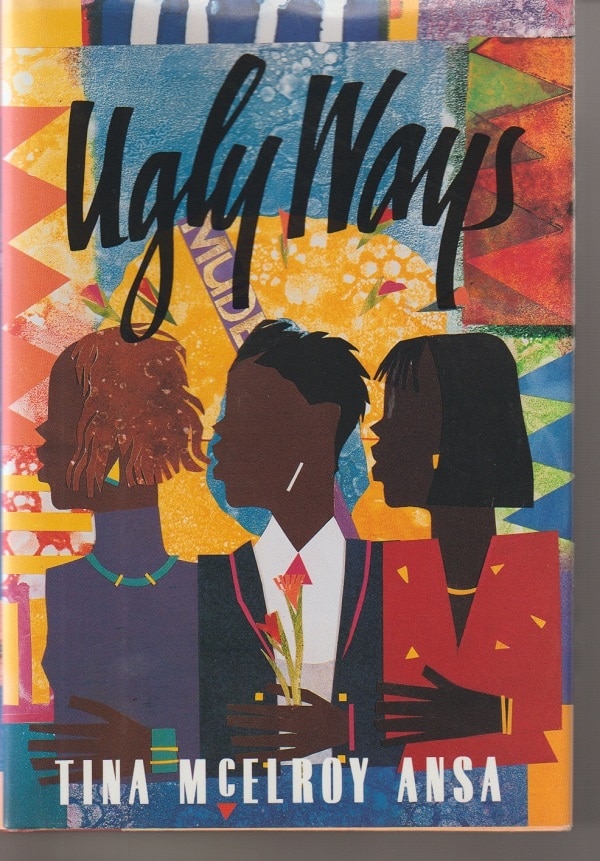

Betty Lovejoy and her younger sisters Emily and Annie Ruth, all successful black women, have come together in Mulberry, Georgia, to bury their mother, known by the family nickname as Mudear.

But it’s far from a lovefest.

As with any group of sisters, there are tensions, even though these women are, for each other, best friends in the world. Their disagreements, though, are minor, compared to the anger they hold for their mother. And, during the two days in which they prepare for the memorial service, they dig deeper and deeper into the pain she caused them.

Such as when Betty, the only daughter still in Mulberry, decided to open a second beauty salon and, because of that extra work, would have to hire someone to come by her parents house to clean and fix their meals. She just couldn’t keep doing it herself.

“Well, daughter, if your conscience doesn’t condemn you, why should I?” Mudear had said, then she hung up the phone in Betty’s face. Betty, standing with the dead phone in her hand, could just imagine Mudear turning back to the wide-screen television and with the remote control turning the sound back up, ending the audience.

It was one of the two ways she had dealt with her children for at least the last thirty years: either she drifted off to her own thoughts while they talked or she cut them off dead.

In fact, that was one of the reasons that Annie Ruth, a television anchorwoman in Los Angeles, called rarely.

Annie Ruth said it infuriated her to have Mudear just hang up in her face whenever she was tired of talking. “It just makes me want to go through the phone and rip her throat out,” she would hiss [in an immediate phone call] to one of her sisters.

“Reversed the natural order”

In the Lovejoy household and family, Mudear was a force of nature. She cowed her husband Ernest and her three daughters with her huge personality, and ground them down with her regal demands to such an extent that the sisters made a pact among themselves never to give birth to a child, for fear of turning into another Mudear.

For the past three decades — ever since “the change” — Mudear lived by her own rules. She never left the house although she mined her children and the one friend she talked with on the phone for the town gossip — and then made pronouncements about all the failings, faults and foibles of the people she no longer saw as well as those she’d never met.

As for the household duties, those were shifted onto the shoulders of Betty the oldest and the other two sisters. They were required to feed and clothe each other, getting money from their Poppa to do the shopping — and to feed and clothe Mudear who had her own bathroom and shouted orders from wherever she was for one of her daughters to carry out some task that she wanted done immediately.

Mudear even operated by her own clock, sleeping through most of the day and then staying up all night, usually working in her garden in the dark, thanks to her extraordinary night vision. Indeed, Betty thinks of her as “some strange exotic mixed-up plant.”

During the day lounging around in her freshly laundered [by Betty] gowns and robes and pajamas giving off noxious fumes like carbon dioxide as she made everyone’s life miserable in the house. Then, at night, blossoming and exuding oxygen, coming to life and giving off life in her garden outside. She was like a strange jungle plant that had reversed the natural order of the plant world. Betty had even seen her stoop down and take a bit of her garden dirt in her mouth one night.

“Piddling standards”

Throughout their lives — Betty is now 42, Emily, 38, and Annie Ruth, 35 — the sisters have never been able to explain their mother to friends.

As Emily ruminates during a moment by herself, the situation was odd: The mean things Mudear did to them, well, it wasn’t personal.

She was just doing what the hell she wanted to do. If somebody got in the way, well, that was life.

In fact, they knew that “nobody was really allowed to hate Mudear,” no matter what she did.

She lived and played by her own set of rules or lack of them. She made you feel that you couldn’t judge her by your piddling standards even if those standards were held by most of the world.

“Love the rope”

For Emily, the best way to think of the relationship the sisters had with their mother was to recall a scene from a movie she’d seen on TV about a Vietcong POW. The captured pilot had had his hands tied behind him, and he was hung by a rope from the ceiling, causing agonizing pain.

Later, when he was asked how he survived the torture, he said, “You learn to love the rope.”

It was how she and the girls felt about Mudear.

Regardless of her abdication of responsibility as a mother, Mudear was, as she reminded them from time to time, still their mother. Some respect was due her, Mudear felt, for not throwing herself down a flight of stairs when she was pregnant with each one of them.

Feminist hero?

I first read Ugly Ways in 1993 when it was newly published, and I thought then that Mudear was pretty much a monster. Reading it again, more than a quarter of a century later, I agree with my earlier assessment but with a great deal more nuance.

For one thing, it would be possible at this point, two decades into the new millennium, to portray Mudear as a feminist hero.

Before her “change” in her early 30s, Mudear had been dominated by her husband who even slapped her around at times. He ruled over the family home, giving orders and issuing demands.

Mudear’s name was Esther, the same as the powerful and clever Jewish queen in the Bible, and, like her namesake, she used a small bit of leverage to totally disrupt the power equation in the home. Ernest’s manly pride was hurt so much that Mudear was able to step into the vacuum and start ruling the home in his stead.

A strong personality with an iron will, she succeeded way beyond what Ernest had been able to accomplish in terms of cowing the whole family.

“The hand I fan with”

Still, I’m not sure a feminist would want to celebrate a woman who, in taking power, not only turned her husband’s life into a daily hell, but also twisted and contorted the upbringing of her three daughters and continued through their adulthoods to abrade, upbraid and sour them and their lives — to the extent that they imagined that she was torturing them long distance through “bizarre voodoo rituals.”

Indeed, as Poppa tells them now that Mudear is in her casket at the mortuary, their mother routinely told him,

“Don’t be telling me about my girls. Shoot, they the hand I fan with.”

“Trifling”

Mudear would routinely rail against “trifling women,” asserting that it’s OK for men to be trifling, but “a trifling, slouchy woman” is one who “don’t care nothing” about herself.

The girls never even considered saying what they all had thought at one time or another when Mudear went into one of her tirades about triflingness: that Mudear was probably the most trifling woman they had ever seen. A woman who spent most of her days lying in her throne of a bed or in a reclining chair or lounging on a chaise longue dressed in pretty nightclothes or a pastel housecoat. Doing nothing with her time but looking at television, directing the running of her household, making sure her girls did all the work to her specifications. Then, if she felt like it, some gardening at night.

She did nothing else. Nothing, that is, but wash out her own drawers each night after everyone else had gone to bed.

In other words, Mudear was selfish and destructive. She was useless and lazy. She gathered power into her fists and used it solely for her own comfort.

Hardly a hero.

Slow-motion bomb

Yet, it’s important to say that I found Ansa’s book enthralling.

I found Mudear to be kind of a monster. I hated the way she corrupted the lives of her daughters and her husband — and wasted her own life. But, in doing this, she’s fascinating.

We have all come across people who are larger than the room. They are too big in terms of personality or drive or will. They cannot be ignored.

Mudear is that sort of person.

Perhaps with a different, less diffident husband, she would have been less monstrous. Or maybe with daughters or, at least, one daughter able to stand up to her, to call her on her arrogance and selfishness.

But Ernest and Betty, Emily and Annie Ruth were who they were. They provided a perfect setting in which Mudear could dominate unchallenged.

Reading Ugly Ways is like watching a 277-page bomb explosion in slow motion. The victims of the bomb that was Mudear are being lacerated by her shrapnel, here and there, and everywhere you look, on every page.

Never dull

She is astonishing, and the reader is often left aghast. But she is never dull. She is vibrantly alive in her selfishness and cruelty.

For instance, the sisters would send her photos from their lives, celebrating their joys and successes, and often the photos would be tossed aside without a comment.

Maybe that was best.

[Betty] knew better than to press Mudear for a response to the photographs and accomplishments they chronicled. Her response was always so demoralizing.

No matter what the pictures showed — Betty in her high-school cap and gown, Betty at graduation from cosmetology school, Betty in front of her first beauty shop, Lovejoy’s, at its grand opening — Mudear always managed to say just about the same thing. “God, daughter, your butt sho’ look big in these pictures.”

Patrick T. Reardon

11.25.20

NOTE: I read Ugly Ways the first time in 1993 to review it for the Chicago Tribune.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.