Mark K. Tilsen, a poet and Native-American activist, grew up reading a copy of Voices from Wounded Knee, 1973 that “was coffee-stained and was falling apart by the time I was a teenager.”

Then, years later, in 2016-2017, he took part in the Lakota protest at the Standing Rock Reservation at the border of North and South Dakota. The target was the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline and its impact on water quality and on ancient burial grounds. After that, he saw Voices from Wounded Knee in a different light.

In a note at the beginning of the 50th anniversary edition, Tilsen writes that, now, reading the book

“felt entirely different, so relatable, relevant, and necessary. So many similarities, the impromptu press conferences, the different styles and modes of Rez kids and city Natives. The violent smug indifference of the military and police. So much has changed and so much is the same.”

Tilsen is an Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation on the southern border of South Dakota where the Wounded Knee occupation took place in 1973 from February 27 to May 8. He describes himself as a child of the American Indian Movement (AIM), noting, “My family stood at Wounded Knee during the Occupation and went to fight for the people over and over again in large ways and small.”

Photographs and transcripts

Voices From Wounded Knee, 1973 was produced in the aftermath of the confrontation by alternative press journalists and activists who were in the Oglala encampment during the occupation: Joanna Brown, Barbara Lou Shafer, Robert L. Anderson and Jonathan Lerner. They described themselves as an editorial collective.

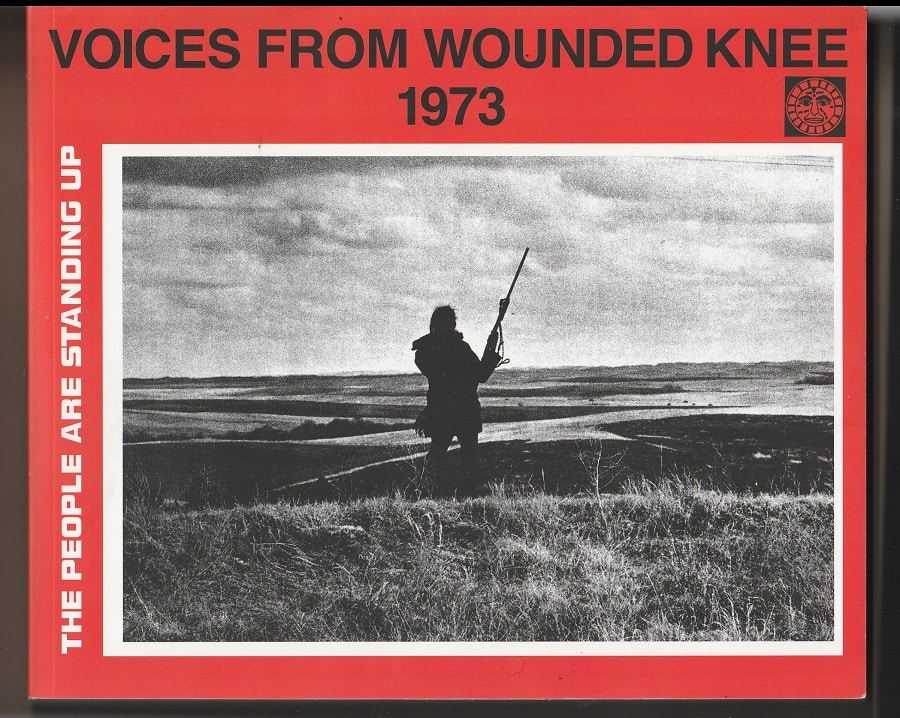

The book is comprised of hundreds of photographs taken inside the town of Wounded Knee when it was surrounded by a cordon of federal marshals, the FBI and police from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In addition, it is filled with three sorts of transcripts: interviews with those taking part in the occupation as it was happening, recordings of over-the-air radio transmissions among federal officers and, sometimes, with Wounded Knee security forces and recordings of meetings of negotiators from the two sides. Beyond this, the book also has various documents, poems and maps.

Pride of place

Knitting together all these materials is reportage by the authors, presented in italics. These generally short sections, often of only a paragraph or two, are designed to put into context the transcripts and photographs of the Native Americans carrying out the occupation.

Whereas in a book of history, the narrative would aim to give a coherent picture of events with the occasional use of quotations, Voices from Wounded Knee takes the opposite approach.

The words of those directly involved in the occupation and the photographs of them are given pride of place.

Similarly, there are times when the authors step back and provide history and background, such as on the American Indian Movement and the horrific Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 in which nearly 300 Lakota people were killed by U.S. Army soldiers. But, often, part of these history lessons includes transcripts of recordings of Oglalas and others telling the story.

Put together in 1974, Voices from Wounded Knee should not be seen so much as a book but as a collection of historical documents, created in the moment — the equivalent, for instance, of the Federalist Papers following the American Revolution or the extensive array of documents (audio and video recordings among them) that the courts and the Congress have collected from the January 6, 2020, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

From the inside

The book describes the occupation from the inside. It tells of the day-to-day existence in Wounded Knee in terms of food and shelter and protection.

It recounts the frequent firefights between the heavily armed federal troops besieging the occupied town and the scrappier Native American security forces. And it describes the deaths of two of the occupiers: Frank Clearwater of the Cherokee and Apache nations and Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont, a local Oglala man. No mention is given of casualties suffered by the U.S. lawmen although news organizations, during the standoff, reported at least one marshal who was wounded.

Given the great amount of bullets fired during the 71-day occupation — the book reports 20,000 federal shots on one night alone — it is amazing that there weren’t more victims. Indeed, it seems that both sides were shooting to miss.

“The human drama”

In an introduction to the original edition, the editors of Akwesasne Notes, publisher of Voices from Wounded Knee, write that, in the year since the occupation, the federal government and the mainstream news media had presented an Establishment version of the events.

That’s why this book is so important. It tells the story by the participants themselves. It contains just what the U.S. representatives said in the negotiations. And gradually, the human drama of a suppressed and oppressed people getting themselves together to restore some dignity to their lives….

Those who occupied Wounded Knee bet their lives that there would be change — and that the change would restore to them their humanity — and would restore humanity to the United States of America at the same time.

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie

Here and there in Voices of Wounded Knee, the editors make reference to the Watergate scandal that was unfolding in Washington, D.C., in the same months that the occupation and stand-off were taking place on the Pine Bluff reservation.

For instance, on April 30 — two months into the occupation but still more than a week before its conclusion — President Richard Nixon asked for the resignations of his two most influential aides, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. Coverage of the scandal was, by that time, white-hot and would grow even hotter during the rest of 1973 and well into 1974 when, in the summer, Nixon resigned.

Federal officials at Wounded Knee complained of having a difficult time getting the attention of their superiors and the White House. And coverage by the news media was certainly affected, as Watergate developments pushed the occupation off the nation’s front pages and newscasts.

The goal of the occupation was to force the federal government to acknowledge the sovereignty of the Oglala over the lands granted by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie on which the United States later reneged. That wasn’t accomplished, but the AIM and Oglala leaders did succeed, at least for a time, to raise the issue of the U.S. treatment of Native Americans.

However, by the time Voices from Wounded Knee was published, such issues had faded from the minds of most Americans as the book’s editors note. And, fifty years later, that remains the case, except when conflicts, such as the Standing Rock protest, flare.

“Catch the spirit”

The editors of Akwesasne Notes, in their introduction to the original edition, wrote that the book represented an important historical document not only for Native Americans but also for all Americans:

We hope it will be seen as American History, not as a document for those who “like to read about Indians.” But most of all we hope that those who read it will somehow catch the spirit of those who put their lives on the line.

Voices from Wounded Knee is certainly an American document. It is a piece of American history, just as the photographs of the beaten and lynched Emmett Till are and just as the first issue of Ms. magazine is.

Among minorities that have been oppressed by the white majority in the United States, Native Americans have gotten perhaps the least attention.

This 50th anniversary publication of Voices from Wounded Knee is an important step in keeping alive the fight of that time to help fuel future battles. As Blacks, feminists and gays have shown, justice for the oppressed is something that can be achieved — at least the beginning of justice. That’s the goal of this book.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.24.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

December 2024, the Akwesasne Notes era ends when our local paper Indian Time ends operations. 1969-2024 (the last NOTES was 1997, the first Indian Time was 1983). I was researching NOTES & VOICES and found these old compatriots of mine. Joanne, Barbara Lou, Bob and Jonathan of Rest of the News. Indian Country Today will carry my story & I hope you see it & comment on these days & events.

I have to add something that became obvious and explained why many people went underground. Upon the 25 year FOIA release of FBI papers, it was shown that the FBI & law enforcement used this book to identify Wounded Knee participants to track down and some were arrested and some were killed. Over 200 Natives & participants on both sides were killed in hostilities after all the FBI actions including the Jumping Bull Ranch incident which resulted in the arrest of Leonard Peltier.