The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, established in Westminster Abbey a century ago, was the first of a multitude of such memorials in countries across the globe. This never-identified warrior represents every individual military person who has given his or her life in defense of the British nation.

In his erudite, lively and affectionate short history of the church Westminster Abbey, Richard Jenkyns relates:

“And so, on 11 November 1920, the body of the Unknown Warrior was laid in the nave and the grave filled with a hundred bags of soil brought from the battlefield. The King, as chief mourner, scattered a handful of French earth upon the coffin — some corner of a foreign field that would indeed be forever England…

“The idea was inspired; the execution was, in some ways, clumsy. The lettering of the inscription is remarkably undistinguished. The tomb blocks the path to the west door. As you walk around the church, you tread upon the names of the obscure and the great — you can hardly avoid it; but no one walks on the Unknown Warrior. And so every procession, however solemn, must veer awkwardly to one side as it passes.”

“The shuffle around the tomb”

More than a dozen English kings and queens are buried in the 1,000-year-old abbey, as well as phalanxes of great British writers, scientists, saints, architects, historians, actors, composers, military men and statesmen. Chaucer’s tomb is there, as are those of Handel and Dickens, Newton and Darwin. And even more luminaries, though buried elsewhere, are commemorated in a large way in the Abbey, including Shakespeare and Milton.

Yet, none is accorded quite the same respect as the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. Coronation marches, royal wedding processions and funeral corteges, as well as everyday visitors, step just a bit out of the way so as to avoid stepping onto this solemn national spot.

At her grand wedding to the Duke of York in the Abbey in 1923, Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon recognized this, as Jenkyns relates:

“As the bridal couple left the church, the new Duchess, showing the flair which would serve her so well as Queen and Queen Mother, laid her wreath on the Unknown Warrior’s grave.”

The Duchess, whose husband became George VI and whose daughter became Elizabeth II, was much loved by the British people during a 101-year-long life.

“She had been at one time queen of a quarter of the world’s population, queen over more people than any other woman in history; and that is something that can never come again.

“But the rituals of death do not change; once again the coffin carried down the nave, again the shuffle round the tomb of the Unknown Warrior; and there her funeral wreath was laid, where she had laid her bridal wreath, seventy-nine years before.”

“A place to pick up women”

Westminster Abbey is quite a place, a structure in which historical events have taken place and a building in which historical eras and figures as well as the myriad aspects of national life are commemorated in a rampant turmoil of art and architecture, great, middling and dull.

Even more, it is a working church, a place of prayer and ritual, of faith and hope.

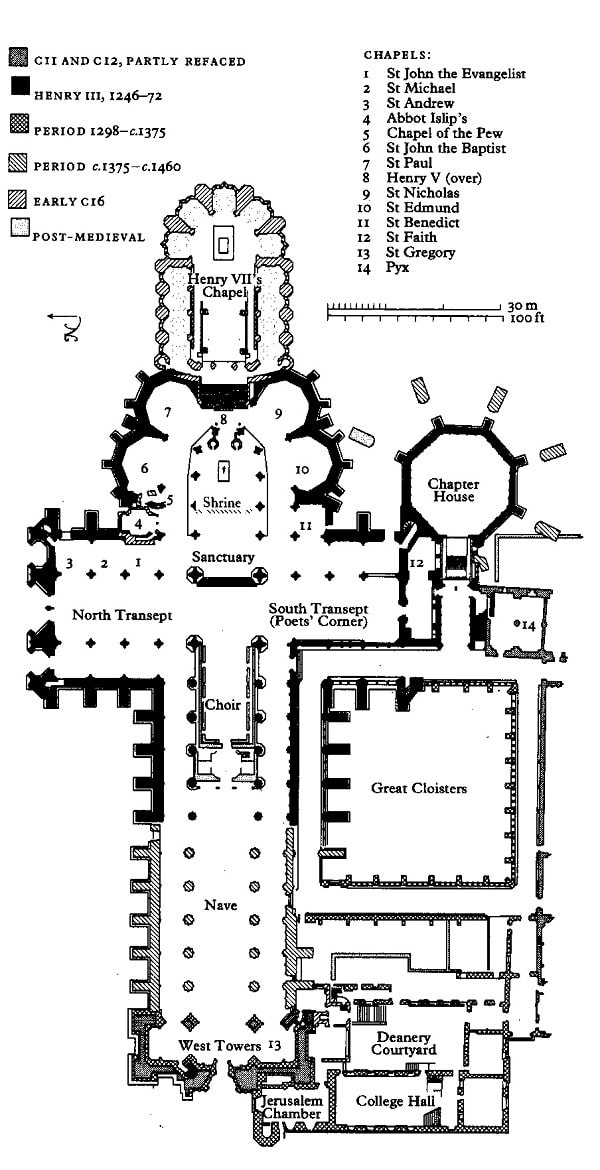

Jenkyns calls the Abbey “the most complex church in the world in terms of its history, functions and memories — perhaps the most complex building of any kind.” Through its millennium in existence (the core of the present structure dates from the 1200s), it has been an abbey and a cathedral and is now a collegiate church, directly under the jurisdiction of the monarch.

“It is the coronation church, a royal mausoleum, a Valhalla for the tombs of the great, a ‘national cathedral’ and the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior…It is one of the high places of Anglicanism, but it houses the shrine of a saint of the Roman calendar, and the principles of Presbyterianism were hammered out within its walls.

“Its chapter house was where the Commons met in the fourteenth century, moving later to the refectory, and the treasury was in the chapter house’s crypt, so that the building was Capitol and Fort Knox rolled into one.

“The Abbey has witnessed many strange sites: Blake saw a vision of angels in it, and Pepys used it as a place to pick up women.”

In addition, he writes, the Abbey “exists as an idea as well as a building, a nebula of memories, traditions and associations…”

Elizabeth I

I went to the Abbey in early September, 2017, on a pilgrimage to the burial place of Elizabeth I, that ever-fascinating, ever-elusive Protestant monarch who somehow, as a young woman, dodged the executioner’s blade and, as a mature woman, ran herd over her hordes of male advisors and more than a few rebels and assassins with nerve, brilliance, deviousness and an ability to turn her personality quirks into assets.

(For the same reason, I also visited the Tower of London to see the Traitor’s Gate where a stubborn and frightened 19-year-old Elizabeth entered the prison that she feared she would never leave.)

At the Abbey, I found Elizabeth’s tomb which she shares with her older Catholic sister Mary I. Actually, “shares” isn’t exactly the right word since, although their bodies may be together inside, the effigy on top is that of Elizabeth. It certainly seemed to me that she had the last word.

A wonderful, delightful mess

But even more important for me than visiting that tomb was my experience of Westminster Abbey which struck me — and I mean this in the best possible way — as a wonderful, delightful mess, an eye-straining kaleidoscope of chaotic and discordant visual elements that, somehow, were held, one might say lovingly, in the light and airy embrace of the church’s soaring walls.

It is such a one-of-a-kind place, a clutter of famous and obscure names — some of the most flashily memorialized were, for me, the most obscure — and clashing architectural styles and colliding sculptural fashions, and real history as a place where important things, over a thousand years, have happened.

And, like my church back in Chicago, St. Gertrude, it was a sacred space where people prayed and focused on the meaning of things and pondered the import of life.

I wanted to be part of that praying, and, a couple days later, I was back at the Abbey for Evensong at 3 p.m. I’d been told that, to attend the service, all I had to do was to queue up near the velvet rope to the left of Newton tomb. I got there a few minutes early and was fourth or fifth in the line.

When the time came for the service, we were led into the area in front of the sanctuary, and those of us at the front, maybe 40 people or so, were directed to take our seats in the choir itself, on both sides. When the choristers entered, they processed to a choir stalls that had been reserved on both sides for them between us non-singers. The rest of the attendees sat on folding chairs to the east of the choir.

When the time came for the service, we were led into the area in front of the sanctuary, and those of us at the front, maybe 40 people or so, were directed to take our seats in the choir itself, on both sides. When the choristers entered, they processed to a choir stalls that had been reserved on both sides for them between us non-singers. The rest of the attendees sat on folding chairs to the east of the choir.

Let’s just say the whole service was pretty spectacular from the singing to the reading of the lessons and prayers.

I tried to go back the next day, Sunday, for Eucharist, but other events got in the way. I’ll be there again — as soon as Covid cries, “Uncle,” and I can get back to London.

“Royal rosebud”

Although my little digression may seem somewhat far afield from Jenkyns’ book, it points up something that I suspect is accurate: Each person who goes into the Abbey experiences it in a very personal way.

Yes, that’s true of everything. In this case, though, the Abbey is such a mélange of stuff — much of it deeply resonant, touchingly human stuff — that its impact as a place and an idea is multi-dimensional. Much different than, say, a visit to the U.S. Capitol or St. Peter’s in Rome or a walk along the Brooklyn Bridge.

For Jenkyns, a classics professor at Oxford, it’s the architecture and art of the Abbey that are of particular interest; he devotes nearly half of the book to these subjects. Even so, he’s got a writer’s ear for descriptions of the Abbey by a wide array of figures and for cogent and affecting anecdotes, as well as a sharp eye for the very human.

For instance, he writes that the tomb for one of James I’s infant daughters, Princess Mary, is “a surprisingly gauche piece,” but her sister, Sophia, who died only a few days after birth, “is more sweetly remembered.” The Latin inscription reads in translation:

“Sophia, royal rosebud, plucked by a premature fate and snatched from her parents, James, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, and Queen Anne, to bloom again in Christ’s rose garden, lies here…”

All around her are hundreds of others, greater and more long-lived, but this “royal rosebud” is poignant in her ordinariness. And her nickname “gives an intimate, family flavour to the baby’s commemoration.” Jenkyns goes on:

“The charm of the inscription lies in the way that the pretty conceit of the rosebud is interrupted by the sonorous recital of formal, royal titles…, only to be picked up again in words which link infancy on earth to life in heaven.”

Little Sophia’s tomb “is in the form of a cradle, realistically carved and coloured…, with the baby’s bonneted head peeping out of the bedding — like any other infant…”

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II is, like her namesake, endlessly fascinating to me but for different reasons. She was just 25 — only six years older than the frightened Princess Elizabeth at the Tower — when she became queen in February, 1952. I was two years old. She’s always been a part of the world I’ve lived in, and, as a companion, she’s been a tranquil presence.

A year after her ascension, she was crowned in Westminster Abbey, and the photo that Jenkyns provides shows a very young woman wearing what appeared to be a very heavy crown.

“The Queen appeared for her anointing, unlike the kings, with her arms bare, and this, together with her youth, enhanced the sense of sacrificial vulnerability.”

In his diary, fashion and portrait photographer Cecil Beaton wanted to be snide, but, as a quote Jenkyns offers shows, he, like the rest of Britain, was falling in a kind of love with his monarch:

“Her pink hands are folded meekly on the elaborate grandeur of her encrusted skirt; she is still a young girl with a demeanor of simplicity and humility. Perhaps her mother has taught her never to use a superfluous gesture.

“As she walks she allows her heavy skirt to swing backwards and forwards in a beautiful rhythmic effect. This girlish figure has enormous dignity; she belongs in this scene of almost Byzantine magnificence.”

Memories

For me, the richest parts of Jenkyns paean to Westminster Abbey are those which deal with human beings acting human. James I and Anne with their sorrow for their “royal rosebud.” Elizabeth I with her bare arms and enormous dignity.

The Abbey is a place of stone and wood, of sculpture and poetry, of hallowed heights and a sacred piece of floor remembering someone unknown.

Most of all, though, as Jenkyns emphasizes, it is a place of memories, as rich in character and emotions as a nation’s cemetery and a child’s last resting place.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.11.20

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.