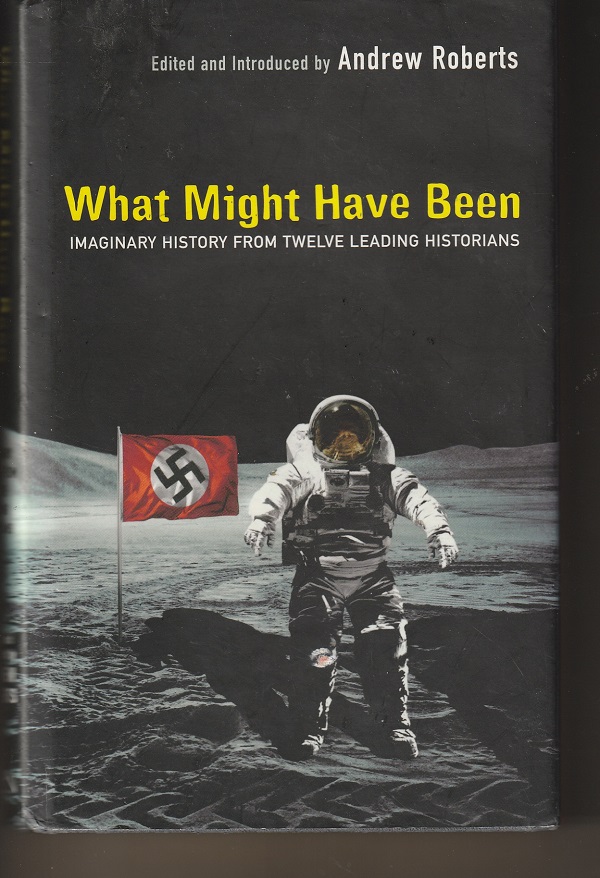

What Might Have Been: Leading Historians on Twelve ‘What Ifs’ of History, published in 2004, is, as its subtitle suggests, a serious work of counterfactual speculation.

Which isn’t to say that the historians don’t have fun.

There is, first of all, the fun of trying to imagine how events might have developed if one or two turns of history went differently.

Such as, if the Spanish Armada had succeeded, permitting an invasion by the forces of the Duke of Parma — Anne Somerset imagines that Queen Elizabeth would have surrendered, and then:

The Spaniards confined her to her chamber and the following day issued an announcement that she had died in her sleep. In reality she had been strangled by her captors.

Such as, if Lenin had been assassinated when he arrived in Russia in 1917 — Andrew Roberts, who edited What Might Have Been, suggests that, among many changes in the historical record, the former Tsar and his Romanov family, instead of being murdered, would have been sent into exile:

Over the next five decades the lives and loves of the Tsarevich and his four grand-duchess sisters were to fill the pages of the world’s society columns…

Such as, if Stalin had fled Moscow in 1941, instead of staying to bolster the defenses there — Simon Sebag Montifiore conjectures that Stalin would have been toppled from power and executed, replaced by Vyacheslav Molotov who would stay in power until his death in 1986 at the age of 96:

Lying mummified beside Lenin, Molotov — this cruel, brutal, ruthless, rigid yet pragmatic Marxist bourgeois — remains the dominant statesman and monster of twentieth-century Russia.

“Imagine a world”

There is also the fun some of the historians have in finding interesting ways to telling their what-if story.

Roberts, for instance, in addressing the speculated Lenin assassination, presents his chapter as if it were an excerpt from a book by his alter ego Andrei Simonovich Robertski, Kerensky’s Triumph: The Russian Revolution and Its Aftermath, written in 1967.

Robertski notes that Lenin, viewed as a minor historical figure, might have been a major figure, given his forceful personality and views, if he’d avoided the assassin’s bullet, leading to “one of the fascinating What Ifs of History.”

Robertski notes that Lenin, viewed as a minor historical figure, might have been a major figure, given his forceful personality and views, if he’d avoided the assassin’s bullet, leading to “one of the fascinating What Ifs of History.”

Imagine a world, if it is possible, in which Lenin was not shot dead as he began to address the welcoming crowd at the Finland Station, but instead went on to put his tremendous energy, eloquence and polemical abilities into attempting to overthrow Prince Lvov’s Provisional Government in 1917.

Today, instead of the liberal democracy that Russia has enjoyed for the past half-century, a creed called Marxism-Leninism might well have extended across much of Russia and Eastern Europe, and perhaps even so far at the Far East.

Robertski goes on from there to sketch what “actually” happened after the killing of Lenin.

It’s clear Roberts is having fun, deciding that, if this happened, then this was likely to result, etc. But he’s serious nonetheless, basing his speculation on real people and how they really acted, in other words, basing his what-if on facts.

Pretty goofy at times

Not all what-if history is so serious. Indeed, it can get pretty goofy at times.

Consider the many novels of Harry Turtledove. On the cover of one — In the Balance: An Alternate History of the Second World War (1994) — Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler stand shoulder to shoulder above the words:

Suppose Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, Hitler, and Hirohito had united to conquer an even greater foe?

That enemy: A technologically advanced alien civilization, calling themselves The Race.

On the cover of another — The Guns of the South (1992) — Confederate General Robert E. Lee stands there, holding an AK-47, a weapon that would not be invented for more than eighty years by a nation that, at the time of the Civil War, didn’t exist.

An endless supply of these Soviet-made automatic rifles, as well as other advanced technology, medicine and intelligence, has been handed over to Lee and the rebels by a group of time-traveling neo-Nazis, akin to the Ku Klux Klan, from late-20th century South Africa. Their goal: To create a hyper-white supremacist future for the United States.

Societal changes

Such books are a cross between what-if history and science fiction, and, as entertaining as they can be — Turtledove has sold an awful lot of his “alternate history” novels — they’re essentially absurd. They’re not so much about history as about the fantasy of time-travel or an alien invasion.

More serious, though, are those books of speculative fiction (another name for sci-fi) that imagine what everyday life would have been like if history had gone a different distance.

For instance, Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004) envisions anti-Semitism on steroids in an America in which the Nazi-leaning Charles Lindberg defeats Franklin D. Roosevelt for president in 1940, and Pavane (1968) by Keith Roberts pictures England after an assassination of Elizabeth I and a victory of the Spanish Armada.

And what if Hitler and the Axis nations had won World War II? That’s the underlying subject of Fatherland (1992) by Robert Harris, about a Berlin police detective in a Nazi-triumphant world, and The Man in the High Castle (1962) by Philip A. Dick, a story about a world in which Franklin Delano Roosevelt was assassinated in 1933.

These novels are knee-deep in the world of regular people, like you and me, and they reflect the sorts of societal changes that a different leader or a conquering army might impose.

Humans have had to deal with such things down scores of centuries. In this way, these novels much more plausible than a story based on something that this world has never before experienced, such as time travel and conquering aliens.

“Her extraordinary air of melancholy”

Some of the chapters in What Might Have Been are more interesting than others, and a lot of that has to do with the skill of the writers. A professional historian needs to be able to do research at great depth and synthesize a great amount of material. But not all are great writers.

Antonia Fraser is.

Not only is Fraser the author of the highly regarded Mary, Queen of Scots (1969), Cromwell, Our Chief of Men (1973) and The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith (1996), but she’s also written widely popular detective novels.

Her chapter is about what might have happened if, in 1605, the bomb, set by Catholics underneath the House of Lords, had exploded, killing King James I and most of his family as well as hundreds of Protestant notables of the kingdom. She envisions a Catholic regime set up around the King’s surviving daughter, and her chapter begins:

The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II took place on a fine, fair day in January, 1606 — the fifteenth to be precise, in honor of her glorious predecessor, the first Elizabeth, who had been crowned on that very day in 1559….

At the age of nine and a half, Elizabeth II might have been in danger of being dwarfed by her imposing surroundings. Fortunately she was tall for her age (taking after her late mother, or perhaps her grandmother Mary Queen of Scots), her appearance further enhanced by the dignity of her bearing, on which all commented….

The other aspect of the new queen’s appearance noted by all the spectators both along the route and in the Abbey itself — but not mentioned publicly — was her extraordinary air of melancholy.

“Inappropriate?”

The chapter by Roberts about Lenin is interestingly told, but I’m not sure what I think of his decision to identify the assassin as

Lev Harveivic Oswalt, an odionokiy volk (lone wolf) gunman with a Baltic patronymic, whose motive has never been satisfactorily established since he himself was murdered in police custody the very next day by a man with underworld connections.

That’s more than a bit too cute. But it’s not as off-putting as the chapter by David Frum on what would have happened if Al Gore had become U.S. President in 2000 instead of George W. Bush.

Framed as a transcript of a conference by Gore and his aides in the aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001, Frum, a former speechwriter for Bush, goes for the burlesque in ridiculing Gore.

The low point of the chapter — I’m sure Frum considered it the high point — comes when, instead of calling the terrorist attacks barbaric or uncivilized or savage, Gore says:

“Perhaps we could say that we regard these attacks as….’inappropriate?’”

That, I have to say, is pretty goofy. And I’m sure it got a lot of yuks from the Bushites who were sure their actual president did much better in the face of the 9/11 crisis.

Given what’s been learned since, I’m not sure that’s a case that can still be made.

Patrick T. Reardon

4.12.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.