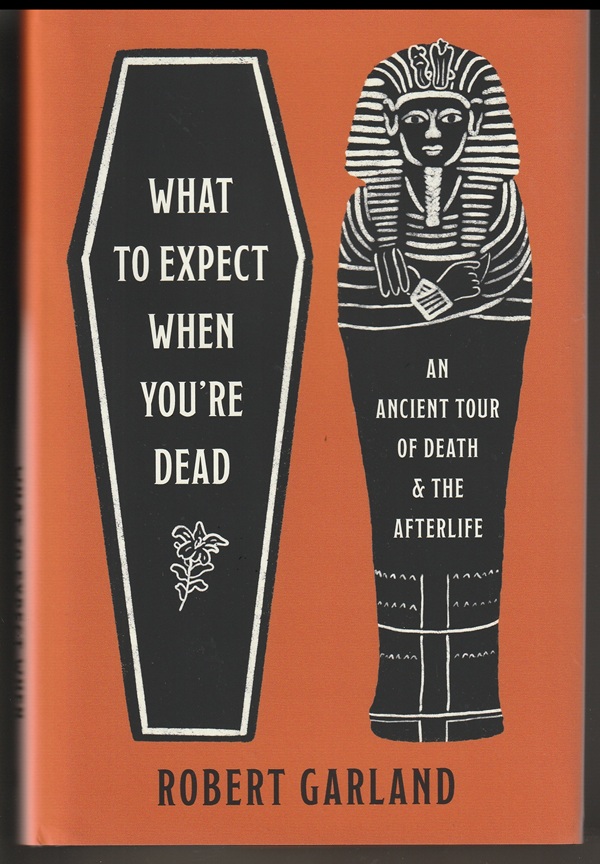

Early on, Robert Garland, a professor emeritus of the classics at Colgate University, lets the reader know his scholarly intentions for What to Expect When You’re Dead: An Ancient Tour of Death and the Afterlife (Princeton University Press):

What I offer here is a comparative study of the practices and speculations that a variety of cultures and religions have produced over time in an effort to come to terms with the greatest mystery of all. Archeological, literary, epigraphical, and iconographical data all have much to contribute. Overall, we know rather more about eschatology, viz beliefs about the afterlife, than we do about mortuary practices, which show up only rarely in our sources and whose origins are unfathomable.

In other words, how have people at different times and places thought about what death means and what, if anything, happens afterward? Perhaps no other question in human life is as essential and serious as this one.

Two personal notes

Garland writes that, in his book, he will focus mainly on ancient peoples and cultures — Greek, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hindu, Zoroastrian, Etruscan, Roman, Jewish, Early Christian, Islamic and others with even some references to modern day.

I have organized my inquiry around questions we might ask of someone who has personally experienced the afterlife — what choices we need to make before our departure, how we should prepare for our last moments, what we’ll encounter on the other side of life, and finally what to expect, so to speak, if there’s nothing to expect.

It sounds very scholarly and serious. But, then, Garland, who is seventy-seven, has two things, less scholarly in nature, to say:

On a personal note, I should point out that my occasional levity is not intended to be disrespectful to the dead, whom I’ll no doubt be joining soon enough…

On another personal note, I do not believe in the life everlasting. As a born skeptic, however, I am prepared to be pleasantly, or more likely in my case, unpleasantly surprised.

Garland’s book, however, seems much more personal than those notes indicate. Indeed, it seems to be a very personal book, perhaps more than he even realizes.

It is as if he is whistling as he walks past a graveyard. Seriously.

“His taste buds”

Throughout What to Expect When You’re Dead, Garland’s writing is brisk and almost hearty, such as when he describes the great treasures that were often buried with the affluent and then what was put in the grave with those not-so-affluent:

Throughout What to Expect When You’re Dead, Garland’s writing is brisk and almost hearty, such as when he describes the great treasures that were often buried with the affluent and then what was put in the grave with those not-so-affluent:

The poor, of course, will have to make do with the bare essentials — say, a rusty dagger, a chipped pot or two, and a cheap ring — just as they do in this life. They muddled through up here and they will no doubt muddle through down there.

Or when talking about the torments that were believed to be inflicted on certain figures, such as the Greek mythological figure Tantalus who stole secrets from the gods:

The dead must at least have neural systems since otherwise it would be pointless to torment them. The punishment meted out to Tantalus, who is perpetually denied fruit to satisfy his hunger and water to slake his thirst, has meaning only if his gustatory receptors are fully up and running. Or — here’s a chilling thought — were his taste buds restored precisely in order to cause him torment?

Or the way the Egyptians thought of what follows death:

The Egyptian afterlife looks like a pretty sweet deal, but we should not ignore the fact that it was dependent on circumstances beyond one’s control, since there was always the very present possibility that tomb robbers would break into the coffin to seize the jewelry and other valuables. No text explains what the consequences for the dead would have been in such circumstances, but we can hardly doubt that they must have been dire.

Or the high cost of Egyptian tombs:

There were, however, ways to economize. If a rock-cut tomb was beyond your means, why not settle for a so-called soul house? This was a cheapo model of a tomb complete with a porticoed façade, about a foot cubed.

Or the food that would be left at the tomb for the dead body:

Can we seriously think that ancient people believed that the food that lay moldering beside the tomb contained nutritional value for their dead?

Garland’s approach could be described as playful or maybe breezy. But it’s something less innocent. Despite his personal note about levity, it comes across as disrespectful.

Wholesale ridicule

Garland doesn’t engage in “occasional levity” in What to Expect When You’re Dead.

Instead, he takes his heavily researched mass of information — nearly ten percent of the book is made up of source notes — and employs it in wholesale ridicule.

The book he has published here mines hundreds of studies of the idea of death in ancient and more modern cultures, and, as far as I can tell, Garland is accurate enough in reflecting the findings of those researchers in terms of data, but not tone.

There is an underlying attitude to What to Expect When You’re Dead which seems to say that every generation of humanity going back to the beginning was completely misguided, deluded and birdbrained when it came to death.

This subtext seems to be rooted in Garland’s own skepticism. Yet, scholars from the start of scholarship have recognized the need to set aside prejudices when trying to understand any subject, whether how planets move or how a seed germinates or how a human being deals with the reality of death.

The logic test

Garland’s text is often flippant and glib, and his subtext suggests that everything anyone in the past ever believed about what happens after death was rather silly.

He writes as if it’s easy enough to prove the stupidity of death beliefs, such as when he says that the ancient Greeks must have thought — har, har — that, after death, Tantalus’s “gustatory receptors” must have been restored to him so that he could be tormented.

The death beliefs of ancient and more modern cultures have to do with belief. Yet, Garland writes as if each idea about death needed to pass a logic test, as if each idea about death had to make sense.

Why do we study the thinking and beliefs of ancient cultures or any culture? It’s not to expose their illogic.

The goal of such research is to get a sense of how these humans coped with their world in a psychological and cultural way. That is important to us because we are trying to cope with our world, specifically, in this case, trying to cope with what it means for each of us to die. Or, as Garland says cheekily in the first sentence of the book:

Studies prove that everybody dies eventually.

“Ceaselessly? Seriously?”

Garland makes fun of ancient and more modern beliefs about death throughout What to Expect When You’re Dead, but he really lets out the stops when it comes to Christianity’s idea of heaven and hell.

He quips about a quotation from St. Paul:

Even when he’s reeling off a long list of all those who will be denied entry into the Kingdom of God, viz “those who commit fornication, impurity, licentiousness, idolatry, sorcery, enmities, strife, jealousy, anger, quarrel, dissensions, factions, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and things like that” — it seems the list might go on forever — St. Paul does not suggest that these miscreants will actually be punished.

He sees a mention in the Book of Revelations of a burning lake in hell as an occasion for “levity” over the lack of clarity in a book of visionary prophecy:

Though the lake clearly goes on burning forever, it remains unclear whether the ungodly will undergo eternal roasting or whether, once consumed by fire, they will cease to exist, which, as we have seen, is what the Egyptians held to be the fate of the wicked.

And he just can’t take it anymore when he has to deal with one early Christian’s idea of what it is like in heaven:

Unlike Muslims, Christians have never succeeded in making Heaven seem very colorful, often reducing it to a vaguely apprehended beatific vision….Saturus, St. Perpetua’s spiritual teacher, had a vision of Heaven as a garden where a choir chants ceaselessly, “Holly, holy, holy.” Ceaselessly? Seriously?

Seriously, is this how Garland approaches scholarship?

Patrick T. Reardon

5.27.25

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.