Kate Wilhelm envisions a community of clones as a really dysfunctional family.

Wait, that’s not quite right.

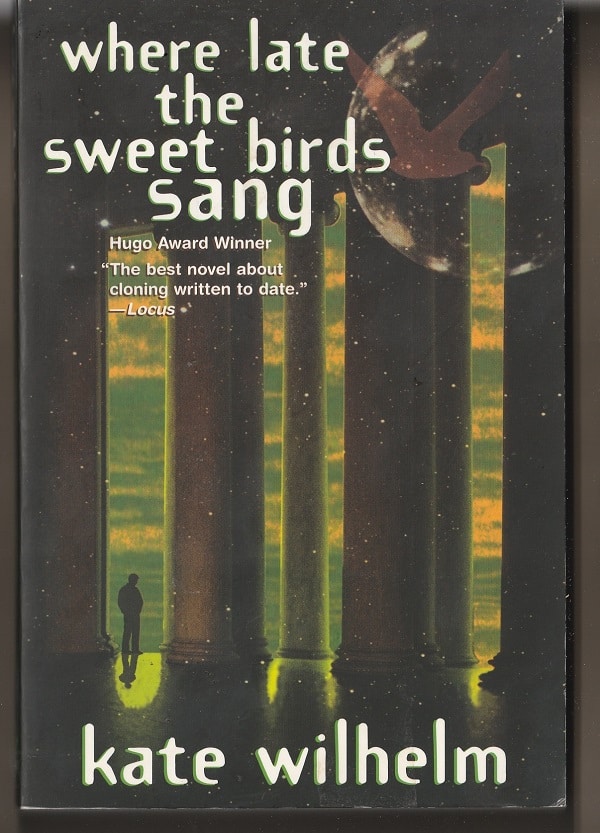

In her 1976 science-fiction novel Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang, she envisions a community of clones as the most functional family you could think of — that is, if “functional” means ruthlessly efficient and totally focused on protecting the family from anything that is unsettling to the community and its members.

Which is to say anything novel, anything that savors of imagination or individuality.

This community of clones is developed in rural Virginia within a long bike ride of Richmond and not too far from the Shenandoah River by a large, extended, very affluent family whose leaders see the world going to hell in a handbasket.

Food is running out, riots are in the streets, and an unprecedented illness is killing off the human and animal populations of the Earth and leaving most of those left sterile.

In a hidden complex

To survive, this family creates a hidden complex of buildings, including a hospital and a top-notch laboratory. Though their numbers will dwindle through aging and death, this family determines to keep themselves — and the human species — going by using the few fertile females and males among them and groundbreaking discoveries in cloning to create new generations.

These generations are multiple replications of the original humans in the family. So that, for instance, a young woman named Celia is cloned into a group of six identical Celias. Although these Celias are called by individual names, they aren’t really individuals but members of a sixsome, each identical, each sharing with the others a telepathic communication. They play together, work together, have sex together as a sixsome or with a male sixsome.

They have many of the same abilities and characteristics of the original Celia, but not all.

There are many such sixsomes of children who are identical to each other and to their non-clone originator.

As time goes on, this generation of clones begins to outnumber the humans and begins to talk of themselves as a new species. Then, they are augmented by clones of the initial clones, and so on.

By the time the humans have died off or gone away, the clone community is working well. But, then, there’s 20-year-old Molly.

A loner in the hive

Anyone familiar with human communities is familiar with Mollys. These are people who march to a different drum. They’re called loners or oddballs or eccentrics. A lot of times, they’re artists.

Of course, in human communities, there’s usually a range of people. Some will be strict rule-followers. Others will be lackadaisical about work, and others will be workaholics. So, a Molly will be seen as different but not all that strange. After all, there is this range of types of people.

But, among the clones, an artist is flabbergasting. The community members are used to every group of clones and every generation of clones working in lockstep for the survival of the community — like bees in a hive, without a queen.

Molly, for them, is a loner in the hive.

For instance, the worst punishment that the clone community can levy against a member is isolation. “A disobedient child,” writes Wilhelm, “left alone in a small room for ten minutes emerged contrite, all traces of rebellion eradicated.”

But Molly thrives on isolation.

“Something else had come alive”

She becomes an artist when she intuits that, in addition to the self that exists in the clone community, there is another self that is able to go outside the everyday and imagine.

The ability to imagine gives her the ability to create. In her case, it’s drawings and paintings that she brings to life out of nothing. And she begins to experience herself as an individual, realizing that she is different from the other five clones in her sixsome, such as Miri:

She looked at Miri’s smooth face, and knew the difference lay deeper than that. Miri looked empty. When the animation faded, when she was no longer laughing or talking [with the others], there was nothing there. Her face became a mask that hid nothing.

Molly had gone through an intense, physically exhausting experience of exploration with other members of the community, some of whom had lost their minds at the randomness of the natural world. Now, she realizes that, for her, everything is different:

She knew something had died. Something else had come alive, and it frightened her and isolated her in a way that distance and the river had not been able to do.

“Bringing unhappiness to all the sisters”

As a loner in the hive, as a community member who is not walking in lockstep, Molly is an unsettling presence. As one community member complains:

“She’s worse than before. She’s bringing unhappiness to all the sisters.”

Molly is bringing unhappiness because she isn’t fitting in as she used to. Her sixsome isn’t a sixsome anymore, just five in a group and her. And her drawings! They are just weird, looking like nothing in “real” life.

“Make her stop working on the drawings of the trip….Make her join her sisters in their daily work, as she used to. Stop letting her isolate herself for hours in that small room.”

“One part was missing”

Molly knows the effect she is having on her sisters — and on the clone community. She tells one of the leaders of the community:

“They don’t like the way my pictures make them feel. They think it’s dangerous.”

And she knows the reason they feel so uncomfortable looking at her pictures:

She thought of them with the [six] Clark brothers on the mat, laughing, sipping the amber wine, caressing the smooth boy/man bodies.

It wasn’t group sex, she thought suddenly. It was male and female broken up into parts, just as the moon broke on the smooth river. The [five] sisters made one organism, female; the Clark brothers made up one organism, male, and when they embraced, the female organism would not be completely satisfied because it was not whole that night. One part of the body was missing…

This unhappiness with Molly will have implications for her and for the community and for later generations of the clones.

The community’s inability to handle an oddball, an eccentric, a loner — an artist — like Molly will have repercussions as the years go on and the community is forced to face unexpected, unusual and novel difficulties.

The phrase, remember, is survival of the fittest. Not survival of those who fit in.

Patrick T. Reardon

8.24.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.