Summer mornings, in my West Side childhood, I would go out on our rickety second-story back porch, and, across the alley, on the worn, gray asphalt of the parking lot/school playground, I’d see thousands of sparkling stars, constellations of slivers and shards of glass set afire in the sharp-angled sun.

Broken glass — brown, green, clear — was a feature of the Chicago that birthed me, the remains of beer bottles and pop bottles, shattered out of drunkenness or anger or, more likely, out of high spirits. Large pieces all over the neighborhood, with rough edges sticking up to stab through the thin bottom of a misplaced gym shoe. Tiny bits that embedded into the crevices of the gray playyard surface.

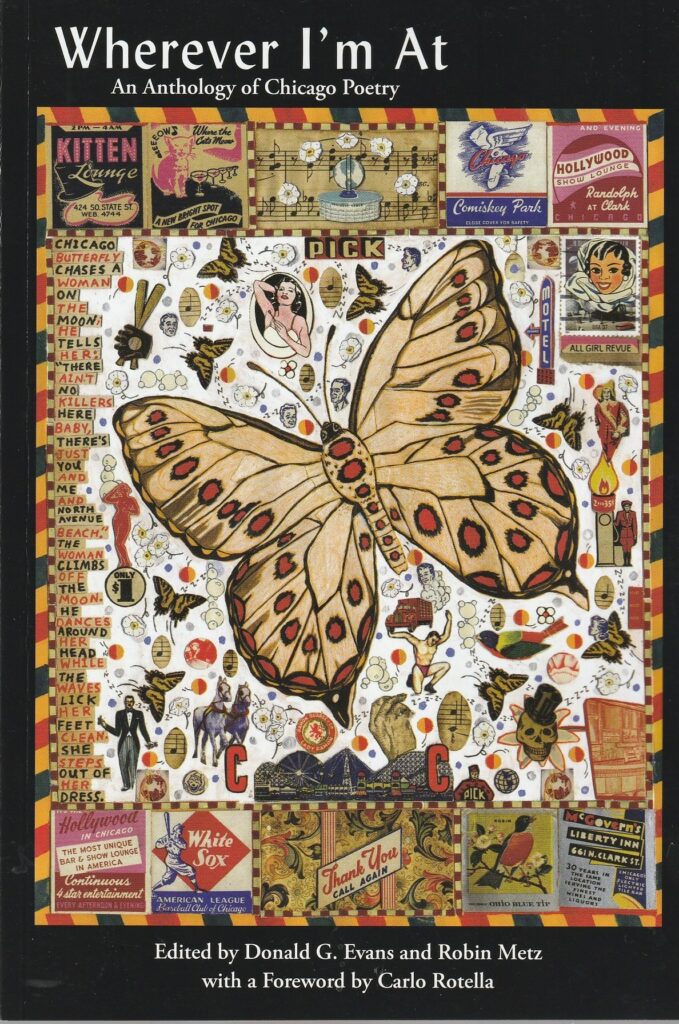

This Chicago of mine was evoked by lines in “Mekong Restaurant, 1986,” a meditation on immigration and longing by Reginald Gibbons in the newly published Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry.

But along these streets ice-winds race. And in summer the raw weedy vacant lots show a jewel glitter sparkling like sequins on fields of ragged green and crumbly gray — innumerable bits of shattered glass under the half-open windows of apartment buildings and ramshackle three-flats…

It’s hard to know how to review this singular collection of work by 134 contemporary poets and 27 artists and photographers. I mean, it’s not as if there is a Chicago school of literature. The sheer exuberant variety of styles, language and subject matter here belies any thought of that.

Each poet is dealing in some way with Chicago, but so much of what these 134 write hints at layers and layers of the unsaid that Wherever I’m At is like being offered 134 novels about the city.

Myriad Chicagos

Or, maybe better put, it’s like being offered 134 Chicagos, myriad Chicagos. Each poem expresses an element of the individual poet’s experience of the city, the tip of the iceberg, in a way, of that poet’s full experience.

For instance, in “Hawk Hour,” Mark Turcotte, who teaches at DePaul University and is a Turtle Mountain Ojibwe, is at the Loyola Red Line station, up on the platform:

Above me the shape of a hawk drowns out the rush of the next ten trains and with its beating wings reached out to stop the sky.

This is the last poem in the collection.

The first is by Elise Paschen, a writing teacher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a member of the Osage Nation. Titled “Kitihawa,” it is about the settlement of Chicago by Kitihawa Point du Sable, a Potawatomi, and her spouse Jean Baptiste:

My husband and I

.

followed the river to its mouth, this spot

where the sun and the moon climb above

the rim of the lake.

Nothing if not inclusive

I’m sure it’s not coincidental that the first and last poems in Wherever I’m At are by Native Americans. Paschen’s reminds us of where Chicago came from. Turcotte’s, of the nature we still live within despite all of our concrete, steel, glass and brick.

The poets in between these two give us glimpses into many Chicagos — Bronzeville and Albany Park, Koreatown and Pilsen, brown, black and white, immigrants from here, there and everywhere, straight and everything else. This collection is nothing if not inclusive, with more women than men among the contributors as well as at least two people who eschew the binary choice.

As Donald G. Evans explains in his introduction, the book was the brainchild of Robin Metz who handed it over as he was dying of cancer. Evans partnered with After Hours Press, a literary journal based in west suburban Elmwood Park, and Third World Press, the largest and oldest independent black publisher in the U.S., to bring the book to publication.

Your personal Chicago

Most readers, I suspect, will approach the book as I did, with their personal Chicago in mind.

Beyond the broken glass of the Gibbons poem, other aspects of my Chicago that appear in these poems include the elevated trains that I’ve ridden for more than six decades, such as the reference in Emily Thornton Calvo’s “My Chicago”: “Spring and fall pass in a blur/like two Red Line trains/slapping the tracks in opposite directions/to close a lapse in time.”

There is an echo to those lines in “In the Intersection, Jackson and State” by Tony Trigilio: “I’m afraid of nature. Orange, Brown Line/trains cross paths, the distant touch of negotiations.” It’s a short poem that begins with the poet crossing Jackson, and it ends with these evocative lines:

One block east, a construction crew

is drilling, their hammers lift from State like smoke.

“Nothing womanish”

Just as those two poems talk to each other in the collection, so, too, does Trigilio’s dialogue a few pages later with the delightful “Yang,” as in yin and yang, by Patricia McMillen. She writes that there is “nothing womanish about me” and goes on to describe how things are “When I’m a man,” such as:

I cross LaSalle Street, halting traffic with an outstretched hand, and all the buildings — Monadnock, Sears Tower, John Hancock — look just like me….Dogs scatter when I’m a man. It’s a day’s work just carrying my shoulders around.

My Chicago — and I suspect the Chicago of many others — includes a history of crappy apartments, such as Lasana D. Kazembe evokes in “Chicago”: “Chicago is a crème colored no-wax/floor camouflaged with raid and roach eggs/and warped wooden porches.”

But he doesn’t stop there. Kazembe pictures my own experience of Chicago’s great grid of alleys:

Winding alleys snake

.

alleys that swallow super rats and del monte cans

snake alleys that swallow men whole men with

holes and shadowy souls called winos

bragging how they are cousins of jesus pitching

pennies in front of the last black quickie mart.

“Smelled like steam”

My Chicago includes elements that Barry Gifford touches on in “The Season of Truth” — a child’s room at the back of the house where “I could scrape my name/in the ice on the window glass with my fingernail” and a streetscape of “Pigeons pecking in gutters,/frozen overcoats at bus stops.”

And K-town, mentioned by Tara Betts in “Donny & Marie on the 72 bus” (“Karlov, Kedvale, Keeler, Keystone, Kilbourn,/Kildare, Kolmar, Kostner, Kilpatrick, avenues…”), where my cousins lived as I was growing up further west in Austin.

And Sandra Cisneros’s “Good Hotdogs,” bought by two little girls with quarters in a store “That smelled like steam” with everything on them but no “pickle lily.” I love that childish spelling!

“Lonely in a large city”

With Raych Jackson and her “Sunrise,” I look askance as “a man [who] invites me to watch the sunrise/like I haven’t lived here my whole life” and I know her ache: “Being lonely in a large city is the only thing I do correctly.”

These are poems that resonate with my Chicago. It’s as if, in reading this book, I was in a large room with all of these 134 poets and we’ve been sharing notes about this city that is under and above, before and behind, to the right and to the left of us. You could, I imagine, bring any 134 Chicagoans into a large room to share notes, and many of the things in this book would be touched on and many things not in this book.

For the 134 poets in this book, the suburbs aren’t very important. Evanston is mentioned in the poems twice; Cicero and Oak Park once each. Schaumburg gets no mention, nor Glenview, nor South Holland, nor Du Page County. Maybe with another group of 134, you’d get some talk about ranch homes and the mall.

I have no idea how these poems would strike a non-Chicagoan. Certainly, they’d give a feel for the city, one probably more authentic than those glossy guidebooks.

“Not about being brave”

And you, Chicagoan — if you read this collection, you’ll find your own Chicago echoed by some poems and not others, you’d find yourself in conversation with these poets and artists.

Maybe your Chicago will, like mine, resonate with “Daredevil” by Stuart Dybek, about a boy who’s not good at sports nor hip nor popular, drawing a crowd as “He’s scaling a railroad bridge/above the open sewer that in the ‘hood/we call the Chicago Insanitary Canal.” On a dare, he’s taking his life in his hands to get high enough and near enough to look into the bedroom of Rita Robles as she dresses for Sunday school.

The poem ends:

Hey, we know a dare’s not about being

brave, but being crazy, which is as close

as some guys come to being cool.

“Marry my aunt”

That’s Chicago humor. Yolanda Nieves details Chicago tragedy in “Remembering the Division Street Riots.”

Nieves remembers playing with a paper doll, a few days short of her birthday, when, suddenly, “screams fill our kitchen/breaking glass shatters/outside/nearby/my father’s footsteps/drum the stairs.”

The family seeks safety, but, for the little girl, the next three days are a time of neighborhood men being shot and beaten: “Bullets hit a target./Near my feet I pick up an empty bullet shell.” They are a time of fear: “The hatred that floats/over us and wants to be our keeper./This hatred is a bar-wire fence that surrounds us.”

Eight are killed in the street:

There were mothers who loved them.

One played baseball.

Another had hoped to marry my aunt.

Your Chicago. My Chicago. And, here, in Wherever I’m At, the Chicagos of 134 poets and 27 artists. Humor and tragedy. Pitching pennies and “pickle lily.” Elevated trains and broken glass.

Patrick T. Reardon

6.28.22

This review initially appeared at Third Coast Review on 6.13.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.