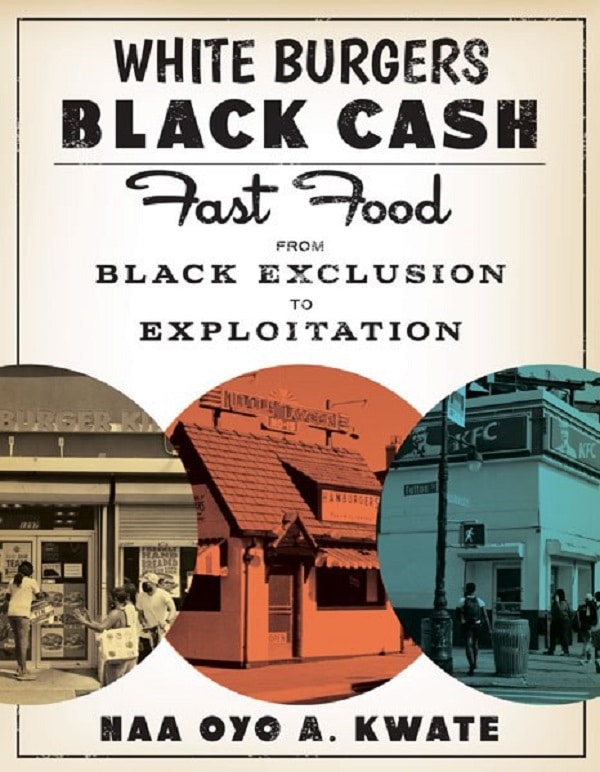

Right from her first page, Naa Oyo A. Kwate makes it clear that the point of her book White Burgers, Black Cash: Fast Food from Black Exclusion to Exploitation (University of Minnesota Press) is that fast food is “a fundamentally anti-Black enterprise.”

Indeed, her title details in a handful of words what Kwate found in her extensive investigation of more than a century of fast food — that such low-cost franchised restaurants initially excluded Blacks as customers, employees, operators and owners and then, because of shifts in the white world and the national economy, focused on African American neighborhoods as cash cows.

Indeed, by the time this switch took place, those Blacks who became franchisees “were in the difficult position,” she writes, “of obtaining their businesses largely in a framework where corporate hired them as miners to extract ghetto gold.”

Kwate is an associate professor of Africana studies and human ecology at Rutgers. In this thickly researched study filled with remarkable and often infuriating findings, she defines fast food as “take-out restaurants serving primarily burgers, fries, and fried chicken, like McDonald’s, Burger King, and KFC.” And much of her research focuses on Chicago, New York and Washington, D.C.

Part of a larger pattern

To be sure, fast food’s discrimination and exploitation of the U.S. Black population, particularly those isolated in low-income, heavily African American neighborhoods, is part of the larger pattern that has and continues to occur in many areas of American life.

For instance, in a chapter titled “Blaxploitation,” Kwate makes the parallel between the way the troubled fast food industry has “mined” Black areas for profit and the way the troubled movie industry did the same with low-budget Black-oriented movies, starting in the late 1960s.

The formula for these films involved pimps, gangsters and other hard-bitten men and women battling “the Man” in tough African American neighborhoods — and winning. And, while they certainly provided a cathartic thrill for Black audiences, their emphasis on criminals and violence in Black areas reinforced racial prejudices among whites, even those who only knew of the films from advertising.

Similarly, the exclusion of Blacks from restaurants and other businesses identified by whites as only for whites during the first half of the 20th century wasn’t limited to fast food.

“What do you think we want?”

Kwate opens and closes her book with James Baldwin’s story from his 1955 Notes of a Native Son about the early 1940s when he was working at a defense plant in New Jersey. He was routinely ignored when he attempted to get food at a self-service restaurant and other places in Princeton.

Then, on his last night, he and a white friend went to the American Diner in Trenton where the counterman asked what they wanted. “We want a hamburger and cup of coffee, what do you think we want?” The counterman refused. And so did the employees at a fancier restaurant where Baldwin’s demands to be served nearly cost him his life.

All Baldwin wanted, writes Kwate, was a hamburger, and his inability to obtain one “stands poignantly for the rest of Black America.”

So too does Baldwin’s description of the rage he felt after this close call, a description that Kwate puts in the final page of her book: “There is not a Negro alive who does not have this rage in his blood — one has the choice, merely, of living with it consciously or surrendering to it.”

A rage in the blood

There is a rage that permeates White Burgers, Black Cash: Fast Food from Black Exclusion to Exploitation. This is a book that is filled with statistics and anecdotes and close examinations of how U.S. institutions and corporate America have used and abused African Americans, and, just under the surface of Kwate’s academic presentation, there is a great anger.

There is the anger of Blacks from the past who weren’t permitted in fast food restaurants and of Blacks from later decades who were brought into the business but were hamstrung by discriminatory corporate practices and of Blacks of today who are demonized by white society for getting fat by eating the fast food that has flooded their communities — communities where other sorts of food places, including supermarkets, have been excluded, like many other businesses, by white corporate decisions to keep away.

Here is how Kwate summarizes her book:

“Baldwin raged because he could not procure the all-American meal at a diner named after America, but what else ought to happen in such a setting? And yet both ends of fast food’s racial spectrum — exclusion and exploitation — can incite the blood-borne rage, because both evoke casual dismissal from organized American society.

“Both evoke contempt for Blackness, rendered outside the bounds of legible humanity. Fast food’s relationship to Black folks is particular but also rooted in the racial impulses in which the rest of American steeps.”

Yes, Kwate’s book is about fast food. But, as she writes in her final sentence, even more, the story of fast food and Black folks “is a story about America itself.”

Patrick T. Reardon

6.8.23

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 4.24.23.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.