In 1971, Linda Nochlin wrote her groundbreaking ARTnews essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” as a manifesto of the new feminist art history, challenging millenniums of art-field tyranny by males.

Thirty-five years later, writing in an essay in Women Artists at the Millennium, she noted that great changes had occurred in art and the study of art, but she was far from complacent.

Feminist art history had entered the mainstream in “the work of the best scholars, as an integral part of a new, more theoretically grounded and socially and psychoanalytically contextualized historical practice,” but it was far from fully accepted, Nochlin wrote in this 2006 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Thirty Years After”:

There is still resistance to the more radical varieties of feminist critique in the visual arts, and its practitioners accused of such sins as neglecting the issue of quality, destroying the canon, scanting the innately visual dimension of the artwork, and reducing art to the circumstances of its production…”

In other words, feminist art historians were being accused, she wrote, of undermining the ideological and esthetic biases of the male-dominated discipline. Which, to her mind, was just as it should be. She wrote that

“feminist art history is there to make trouble, to call into question, to ruffle feathers in the patriarchal dovecotes…At it strongest, a feminist art history is a transgressive and anti-establishment practice meant to call many of the major precepts of the discipline into question.”

Of course, making trouble was exactly what Nochlin had aimed to do with her initial essay.

“No supremely great women artists”

A half century ago, Nochlin ruffled feathers — in the most trouble-making of ways — by taking an aggressively serious look at the question: Why have there been no great women artists? (Even though, in the ARTnews special issue in which the essay appeared, she called it a “silly question.”)

She eschewed defensiveness or overblown claims, and wrote directly and simply:

“The fact of the matter is that there have been no supremely great women artists, as far as we know, although there have been many interesting and very good ones who remain insufficiently investigated or appreciated…”

This might have seemed the raising of a white flag of surrender, but Nochlin attached a second clause to that first one:

“…nor have there been any great Lithuanian jazz pianists, nor Eskimo tennis players, no matter how much we might wish there had been.”

“The fault, dear brothers”

In this single sentence, Nochlin turned the question on its head.

The fact is, she told her “dear sisters,” there was no woman artist who was the equivalent of Michelangelo or Cezanne or Picasso. But that wasn’t because there was something inherently missing in the female human being. The answer was much simpler:

“But in actuality, as we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts, as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male.”

And, then, in the next sentence, she turned to the art-world males who were asking the question, either directly or implicitly — or using the question in an effort to “prove” the lack of talent of women:

“The fault, dear brothers, lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education — education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs and signals.

“The miracle is, in fact, that given the overwhelming odds against women, or blacks, that so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence, in those bailiwicks of white masculine prerogative like science, politics, or the arts.”

“Changed the world”

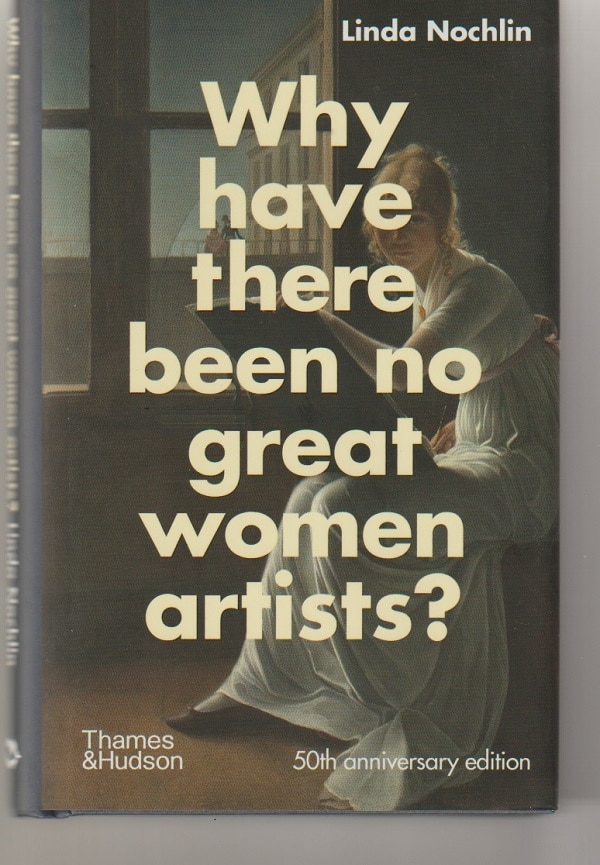

Nochlin’s initial essay as well as her 2006 piece looking back at it are included in Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? 50th Anniversary Edition,” a new pocket-size hardcover, the size of a small bomb, from the British publishers Thames & Hudson Ltd. Also included is an introduction by feminist art historian Catherine Grant and an opening present-day comment by Judy Chicago who wrote:

“It is rare that a single publication by an art historian can be said to have changed the world, but this is exactly what Linda Nochlin did with her 1971 text…

“[F]or the profession, it was a revelation, one that produced generations of feminist art historians (both female and male) who began to excavate history and in so doing, initiated a revolution in the canon that is still ongoing.”

“Golden nugget”

In looking at the support that white male artists were given down the centuries in terms of education, social freedom and opportunity, Nochlin challenged the male-centric status quo of the art world with devastating logic, strongly marshalled facts and a biting wit, as in this sentence:

“Underlying the question about woman as artist, then, we find the myth of the Great Artist — subject of a hundred monographs, unique, godlike — bearing within his person since birth a mysterious essence, rather like the golden nugget in Mrs. Grass’ chicken soup, called Genius or Talent, which, like murder, must always out, no matter how unlikely or unpromising the circumstance.”

That “golden nugget” of Genius — a wonderfully apt and sarcastic reframing of the idea of the “godlike” creator of art — popped up a couple more times in the essay, as Nochlin needled her hidebound male readers.

“Demands and expectations”

More important, though, to her purpose was to make several points, not as an exhaustive recounting of the inequalities in the art world and in art history, but as an indication of the sorts of biases that could be found with a bit of digging.

For example, she raised a parallel question to the one in the title: “Why have there been no great artists from the aristocracy?”

“Could it be that the little golden nugget — Genius — is missing from the aristocratic make-up in the same way that it is from the feminine psyche?

“Or rather, is it not, that the kind of demands and expectations placed before both aristocrats and women — the amount of time necessarily devoted to social functions, the very kinds of activities demanded — simply made total devotion to professional art production out of the question. Indeed unthinkable, both for upper-class males and for women generally, rather than it being a question of genius and talent?

“Rules of propriety”

Another important point, in her essay, came in a section titled “The Question of the Nude.”

Put simply, she noted that, throughout much of art history, it was essential for an artist to know how to sketch and paint the human body, female or male, by taking part in life drawing classes featuring an unclothed model.

This was fundamental for being able to create huge history paintings that were, for many centuries, considered the epitome of visual art. And also of course for being able to produce a nude. And also for knowing how the fabric on a clothed body needed to be portrayed.

However, from the Renaissance until the late 19th century, women artists were not permitted to sketch any nude model, whether female or male, a situation that Nochlin termed

“an interesting commentary on the rules of propriety: i.e., it is all right for a (‘low,’ of course) woman to reveal herself naked-as-object for a group of men, but forbidden to a woman to participate in the active study and recording of naked-man-as-an-object, or even a fellow woman.”

In a reference to the old bridesmaid-bride adage, Nochlin wrote:

“Always a model by never an artist might well have served as a motto of the seriously aspiring young woman in the arts in the 19th century.”

“Unthinkable”

Nochlin pointed out that the question of access to nude models was simply “a single aspect of the automatic, institutionally maintained discrimination against women” that demonstrates

“both the universality of the discrimination against women and its consequences, as well as the institutional nature of but one facet of the necessary preparation for achieving mere proficiency, much less greatness, in the realm of art during a long stretch of time.”

Similar aspects of the discriminatory system, for instance, included the apprenticeship system and the academic educational pattern. In France, she wrote, the academic education process was

“the only key to success and…had a regular progression and set competitions, crowned by the Prix de Rome which enabled a young winner to work in the French Academy in that city — unthinkable for women, of course — and for which women were unable to compete until the end of the 19th century…”

Nochlin, who died in 2017, set off a large bomb in the art world 50 years ago, and the reverberations of the blast continue to be felt.

Far from dated, her essay is fresh and tough and relevant.

Which says a lot for Nochlin’s skill as a writer and as a thinker. And also, unfortunately, about the unequal world we human beings all still live in.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.13.21

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.