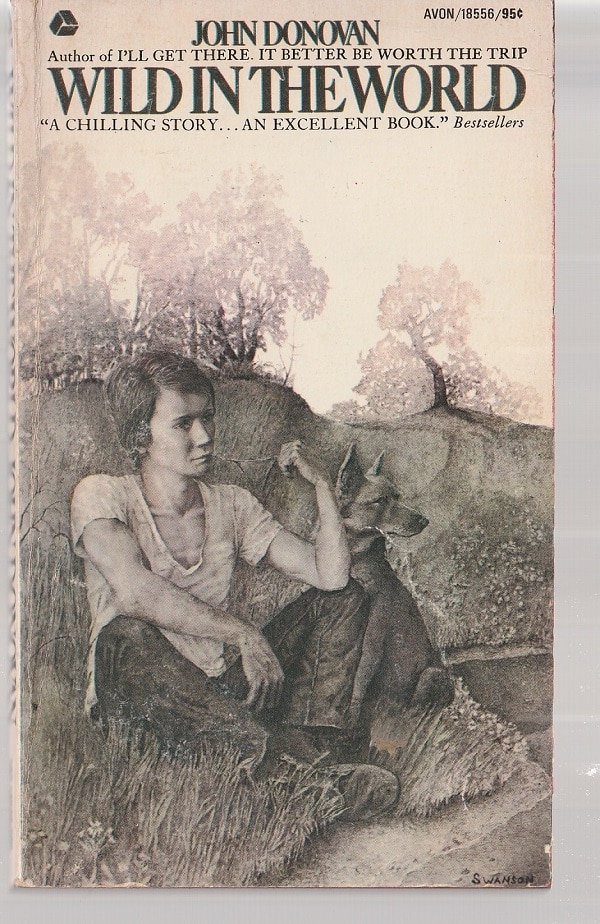

Book review: “Wild in the World” by John Donovan

Published more than half a century ago, John Donovan’s Wild in the World is an exquisitely imagined, delicately rendered novel, terse and forlorn, a fable of the human condition.

No time or space is wasted in this 94-page book, totaling about 22,000 words. Consider its first sentence:

The three brothers, the last living people in a family of seven brothers and four sisters, lived in the New Hampshire home where all of them were born.

The three are Amos, Abraham and John, the youngest of the Gridleys, in his late teens or early 20s. The deaths of their seven siblings are crisply noted, as are those of the parents.

Mrs. Gridley had died when John was born. Mr. Gridley shot himself with his own shotgun on a Sunday afternoon in early October three years afterward, on a visit to Mrs. Gridley’s grave in the Sanbornville cemetery. John was with him. It was John’s first memory.

Life is hard on the homestead, but the three brothers are used to hard work. One, though, gets sick from infection from a homemade fishhook. Another is kicked by a cow during milking. They die. “This left John.”

“That is life”

The family, although close, hadn’t been afraid of the rest of the world. A sister married a used car dealer in another town, but then died. A brother went to college in Boston but got sick and died.

Evidently, John thought, everything that happens to you is out of your hands. You have a time to live; and childbirth, fire, your own shotgun, rattlesnakes, moving away to cities, fishhooks, cows, and diseases kill you. That is life, John thought.

John has thoughts about making improvements on the farm. He doesn’t entertain doubts that he will be able to keep things running by himself. He makes his plans.

These were the thoughts that crossed the mind of a person with a substantial spread of land, with the will to make the spread more productive, but without the support of his brothers and sisters.

Son

Life changes for John when, one day, a large, wolf-like dog shows up. John and the dog aren’t sure what to think of each other, but, eventually, they become friendly. John names the dog Son.

Rarely does anyone ever come to the farm. Some days, John leaves to go to the road to sell produce, to walk to a neighboring farm to rent a couple horses, to make arrangements with summer residents from Boston to mow their fields of hay.

His interactions with other human beings are utilitarian. He’s looking to make some money to be able to continue to live alone on the farm with Son.

The young man and his dog give each other joy. But the memory of death is a constant companion. John’s strongest recollection of his siblings is of their deaths. And of his parents. “Right at the beginning when he killed his mother getting born.”

Many nights he dreams of witnessing his father’s suicide.

“A huge trunk”

For John, Son is a ray of light. The other touchstone for him is a great maple tree near the house.

It was a tree with a huge trunk and had been at the Gridley place before any Gridley within memory lived on Rattlesnake Mountain.

It stood far from the house, but because it was so old, and its parts went over the house, everyone in the family thought of it as the Gridley maple. There were many other trees on the place, but no other tree like the great maple.

It is a simple life for John. At least, it seems that way. Of course, none of us lives a simple life.

Patrick T. Reardon

5.5.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.