William Blake (1757-1827), little known in his lifetime, is now considered one of the leading lights of Romantic Age painting, art and poetry.

He was also a visionary. And, by that, I mean several things, but most of all that he was someone who saw visions.

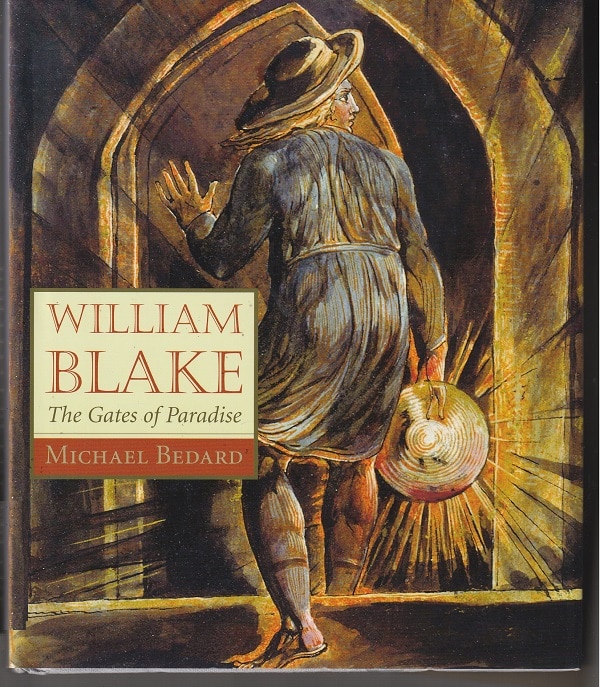

For instance, in William Blake: The Gates of Paradise, Michael Bedard recounts the death of Blake’s brother Robert:

For two weeks William sat at his brother’s bedside day and night, refusing to rest. After a long and bitter struggle, Robert died. At the moment of his passing, William had a vision of his brother’s spirit ascending through the ceiling, “clapping its hands for joy.” He took to his bed and slept for three days and three nights without waking.

William Blake saw visions his entire life, such as at four when “he set the whole house in a flurry by screaming out that he had seen God put his face to the window.”

There were more. Such as when the boy was walking along a rural lane and glanced up to see a tree full of angels. “They were sitting on the boughs, their bright wings flashing in the sun,” writes Bedard.

And more, as Bedard reports:

Like the time he saw the angels moving among the haymakers, or the prophet Ezekiel standing under a tree.

In time he would come to speak of his visions in the matter-of-fact way that we speak of everyday things…

“As a man is, So he Sees.”

As a painter, engraver and printmaker, Blake created art unlike anyone of his time — unlike anyone before or since. Similarly, his poetry is like prophecy.

Both are rooted in the world in which he lived, which is to say a world of visions. As Blake wrote to a patron who disapproved of what he was painting:

“I know that This World is a World of Imagination & Vision. I see Every thing I paint In This World, but Every body does not see alike. To the eyes of a Miser a Guinea is far more beautiful than the Sun, & a bag worn with the use of Money has more beautiful proportions than a Vine filled with Grapes. The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the Eyes of others only a Green thing which stands in the way. Some see Nature all Ridicule & Deformity, & by these I shall not regulate my proportions; & Some Scarce see Nature at all. But to the Eyes of the Man of Imagination, Nature is Imagination itself. As a man is, So he Sees.”

“Dream Dreams”

In the spring of 1803, Blake wrote to a friend that he would be returning to London after an uneasy time in a rural region where he was often criticized by his patron:

“Now I may say to you, what perhaps I should not dare to say to any one else.

“That I can alone carry on my visionary studies in London unannoy’d, and that I may converse with my friends in Eternity, see Visions, Dream Dreams, & prophecy & speak Parables unobserv’d and at liberty from the Doubts of other Mortals.”

Blake’s art and poetry are so idiosyncratic because they are expressions of his theology and spirituality. Indeed, the temptation might be to dismiss Blake as a crank were not the whole range of his artistic work so vivid and compelling.

For him, art whether in paint or in print was the method of communicating his experiences. He lived to “see Visions, Dream Dreams, & prophecy & speak Parables,” and his art was the product of that living.

An outcry

Blake’s writing, painting and drawing was very much an outcry against the dehumanization of the Industrial Revolution. As Bedard writes:

He was a visionary in an age that had no time for visions. This was the age of the machine, the rise of industry, and the spread of factories. The winners were few and the losers many.

Blake witnessed the dark side of the industrial revolution. He saw what the introduction of steam-powered machinery and the rise of the factory system had done to the lives of ordinary men, women, and children. He saw the sufferings of the poor and the oppressed. He saw that a devotion to materialist beliefs withered the human spirit and left people feeling impotent and alone, adrift in a mechanical universe.

Blake as a man and an artist was largely ignored or denigrated by British society, his imaginative works little seen and little read. He was, in his way, yet another victim of the dehumanization of materialism, another victim of an age deaf to visions.

“The stubborn, striving spirit”

At the core of his work are all those other victims, as Bedard notes:

Blake always had the small at heart. Children, the poor, the tiny creatures of nature; it is these that had his love.

Against the massive power of the “dark Satanic Mills” that confine the human spirit, he sets the stubborn, striving spirit of small things acting in harmony and joy.

Through his visions, Blake saw the harmony and joy of life, behind the veil of “reality.” He loved those small beings, the children, the poor and Nature’s creatures.

And, like them, his was a “stubborn, striving spirit.”

Patrick T. Reardon

1.18.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.