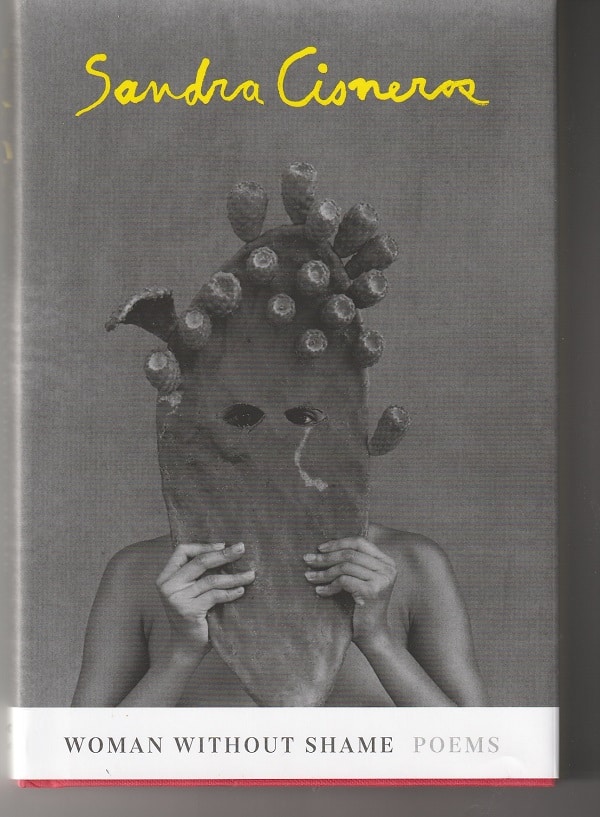

In her new book of poetry Woman without Shame, Sandra Cisneros looks aging in the face and laughs. She laughs at the frenetic lusts and couplings of youth — at broken hearts and confusions. She thumbs her nose at her prudish Catholic upbringing and, lovingly, at her prudish Catholic mother. She embraces herself and giggles. And death?

In a playful jumping off from Dylan Thomas’s 1938 poem “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night,” Cisneros writes in “Canto for Women of a Certain Llanto” that she’d rather go without underwear than put on ugly stuff made for women of a certain age: “Rage, rage. Do not go into that good night wearing sensible white or beige.”

She is writing about herself and other women “who have squash-/blossomed into soft flesh,” women whose once lacy undergarments have been replaced by “feed sacks and ace/bandage straps. Pachydermian./Prosthetic. A cruel aesthetics.” These are garments meant to exile lonely female souls “to the Siberia of celibacy.”

Will no one, she asks, create lingerie “for women of exuberance”? So, she does herself:

In my imagination I create a holster

to pack my twin firearms. My 38-38’s.

A beautiful invention of oiled

Italian leather graced tobacco golden,

whip-stitched, hand-tooled

with Western roses and winged scrolls,

mother-of-pearl snaps

and nipples capped with silver aureoles.

“Push a truth out of my womb”

Cisneros, who was born in Chicago in December, 1954, is a major figure in Mexican-American literature, best known as the author of the 1983 book The House on Mango Street, a perennial high school text with more than six million copies in print. Her fiction includes the hefty novel Caramelo (2002) and three novellas — Have You Seen Marie? (2012), Pura Amor (2018) and Martita, I Remember You (2021) — as well as a short story collection, Woman Hollering Creek (1991). Her memoir in the form of a collection of essays, A House of My Own, came out in 2015.

Through it all, Cisneros, who started as a poet, has continued as a poet. In the acknowledgements section of the new collection, she notes that she has written poetry “because I had to push a truth out of my womb” — needed to create the poem but felt uncomfortable putting it out for people to read. She came to understand that “poetry had to be written as if I could not publish it in my lifetime. It was the only way for me to get past the worst censor: Myself.”

In two previous collections — Loose Woman (1987) and My Wicked Wicked Ways (1994) — Cisneros depicted a strong-minded, strong-willed woman making her way through the pain, challenge, connections and comedy of life.

And the woman in most of the poems of Woman Without Shame is similarly strong-minded and strong-willed, but now no longer young. And, it seems, no longer censoring herself at all.

“In training to be a woman without shame”

Indeed, from the perspective of her late 60s, Cisneros pulls out all the stops in recounting a sweaty, visceral, intense life that wasn’t always happy but was always vivid and passionate.

Consider the first poem in the collection “Tea Dance, Provincetown, 1982” in which a 28-year-old Cisneros has a bisexual lover, “skittish as a kite.” But he’s a minor presence in a summer when she spends her nights at a boy bar, dancing “in one/collective/zoological/frenzy,” with every one of the young men in the entire room for every song, the only woman there.

During the day, she is teaching “myself to sun/topless at the gay beach,” explaining:

It was easy to be half naked

at a gay beach. Men

didn’t bother to look.

I was in training to be

a woman without shame.

.

Not a shameless woman,

una sinverguenza, but

una sin verguenza

glorious in her skin.

In another poem, in one of the collection’s five sections, “Cisneros sin censura” (Cisneros uncensored), she opens with a poem titled “Mount Everest,” and its playful first line is: “Because he was there.”

He lived in the Old Town neighborhood. She was 28, and he was “An empire to conquer./A foreign language to master./A notch on my unchastity/belt when my notches/were few.”

“I fall in love all by myself”

Cisneros looks back from the perspective of nearly four decades at her younger self with affection, understanding and humor. Not so much for the many men with whom she had sex on a bed or a desktop or a train. Well, except for comedy. She has a lot of that for them in “You Better Not Put Me in a Poem.”

It opens with descriptions of the penises of some of the men — “a long curved scimitar like a Turkish moon…a fat tamale plug…a baby pacifier…a lightbulb” — and then the men themselves. One, for instance, “liked to pull it out like a switchblade when least expected.” Another “was married to somebody. A string of somebodies.”

Making fun of these men, though, Cisneros doesn’t spare herself: “I sent one a twenty-seven-page letter wrapped around a brick for dramatic effect.” Another was a male prostitute “who made/Love like a water-hose drowning a riot.”

She tells of sending a $100 bouquet to a bartender even though he was terrible in bed because “I was grateful./I was needy./I was young.” And, in explanation, she adds:

I was/am/always will be a romantic.

.

Which is the same as saying: I fall in love all by myself.

“You better not”

At the end of the poem, a lover appears who, as he kicks off his cowboy boots and unzips his tight jeans, says, “You better not put me in a poem.” And, as he said it, Cisneros knew she would.

As her mother knew. In “My Mother and Sex,” Cisneros writes that her mother gave birth to seven children, but, when a sex scene came on television, “She’d shriek and/Scamper to her room,/As If she’d seen/A rat.”

Maybe it was for this reason, maybe for that. There’s no way to know for sure because “She never talked of sex.//Especially not with me./She said/I put everything/in a book. Agreed.”

The poem, however, isn’t really about sex. It’s poignant meditation about the way her father worshipped his wife (“His Mexican empress”) but had no idea how to please her. She loved classical music, opera, books written by “Herculean. Brilliant. Men.” But her husband loved the TV variety shows: “Father mesmerized by/Mexican, thick-thighed floozies—/Mother’s word, not mine —/Shaking their hoochie-coohies.”

Another poignant poem also features her parents, “Letter to Pat Little Dog After Losing Her Son.” It’s a kind of a testament to the depth of life beyond what can be seen. Cisneros writes to her friend: “And I know as fact/we continue to receive love after/this thin life.” She explains:

My father speaks to me

like the wings of a stingray.

My mother shimmers in air,

a silver moth. I know when

they are here. As in life,

different as ever.

One is water.

The other atmosphere.

A pig who thought he was a dog

As playful as Cisneros is about herself and her lovers and her family and essentially everything, there is, in these poems, a profound respect for each individual, including herself.

She finds humor everywhere because everyone, including herself, is pretty goofy — swayed, swirled, skittish as a kite. And because, behind the comedy, is great sadness and pain.

For instance, in “El Hombre,” she writes about a gringo named Alan who, on his daily drive, would see dogs run from a squatter’s shack and give chase to his car, followed by a pig “who thought he was a dog.” It’s a funny image….

Until one day the pig isn’t there.

The dogs disappear too.

One by one by one.

.

Alan shrugs.

When un hombre is hungry,

There is no one to blame.

“When in doubt”

In Woman Without Shame, Cisneros finds fault with those in charge, those who lord their power over the powerless, those whose greed feeds violence. These are the ones to blame.

But her focus is on all those goofy individuals, like her, and the paradoxes of life. She writes: “To tell the truth/I don’t want to see/someone my own age/naked. Nor have/him see me.” It’s not about modesty. “More akin to fear/we might laugh.”

Woman Without Shame ends with “When in Doubt,” the phrase that begins all but the last verse, such as “When in doubt,/Greet everyone as you would the Buddha,” or “When in doubt/Make life’s major mistakes.”

As the poem ends, Cisneros writes that we are all on a caucus race, a race in Alice in Wonderland with no rules:

There is no start.

No finish.

Everyone wins.

There is faith and hope there in the meaning of life, and Woman Without Shame is filled with faith and hope in you and me and each of us. No shame in that, at all.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.8.22

This review originally appeared at Third Coast Review on 10.10.22.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.