In the fall of 2003, Sebastian Smee, the art critic of the Daily Telegraph in London, described a mid-19th century painting by British artist J. M. W. Turner as “an almost unbelievable vision of swirling blue, orange and white light thrusting through fog.” His colleague, Rachel Campbell-Johnston of The Times of London, wrote that the picture was “so spectacular, that like the shadowy group of figures on the foreshore, you can only stare and wonder.”[1]

The painting, on display in a major exhibition of Turner’s late seascapes at the Manchester Art Gallery, was Rockets and Blue Lights (Close at Hand) to Warn Steamboats of Shoal Water. A century earlier, it had belonged to former Chicago mogul Charles Tyson Yerkes and was displayed in his London office.[2]

American writer Wesley Towner waspishly suggested that Yerkes kept it at the office “as a prestige factor, to impress the monied lords of Britain.” However, in a magazine article shortly after Yerkes’s death, Edwin Lefevre wrote that the mogul once told a friend, “I spend more time in my office than anywhere else, and I love to see it. That’s why it’s here.”[3]

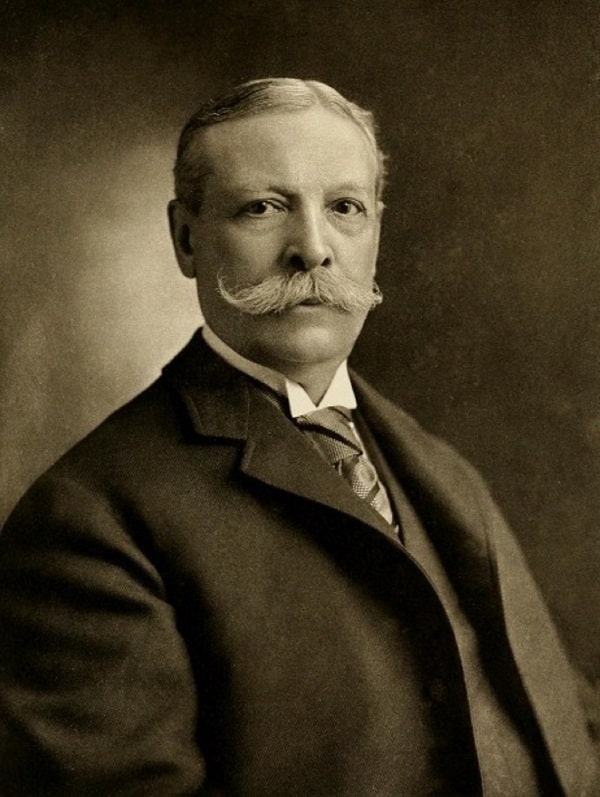

Yerkes was vilified by many of his contemporaries as a corrupt predator and has been demonized by later writers as a “corpulent plunderer,” a devil, “a financial adventurer,” a carpetbagger, “an irrepressible predator,” a pirate, “the prototype of the money-grabbing tycoon” and “a five-star, aged-in-oak, 100-proof bastard.”[4] Yet, as I have written in my book The Loop: The ‘L’ Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago, he was a transportation visionary, the man responsible for the creation of Chicago’s elevated railroad Loop and for the long-stymied expansion of the London Tube system, an entrepreneur who played an enormous role in fashioning the future of two major modern metropolises.[5]

A preeminent U.S. art collector

And, ignored today in nearly every book on the Chicago history of his era, Yerkes was also one of the nation’s preeminent art collectors at the turn of the 19th century.

Today, at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, visitors can study Rembrandt van Rijn’s imposing 1632 Portrait of Joris de Caullery.[6] Characterized as “glorious” by a noted expert on Dutch art, the painting is “one of Rembrandt’s most distinctive early Amsterdam period portraits — notable for its warm, glowing background.”[7]

A century ago, Joris was one of the treasures that Yerkes showed off to visitors to the art gallery in his Chicago mansion on Michigan Avenue.[8] There were hundreds of other artworks displayed there and later in the two art galleries in Yerkes’s even larger mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York.

Another work in Yerkes’s art collection was Francesco Guardi’s View Up the Grand Canal toward the Rialto (1785), now at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and described as “a superlative example of Guardi’s art at full maturity, a vision of [Venice] which captures with the utmost intensity its luminous splendor and its bizarre magic.”[9]

Also owned by Yerkes was Frans Hals’ Portrait of a Woman (1635), now in New York at the Frick Collection. Called “a masterpiece” by one of his contemporaries,[10] the painting shows a woman in late middle age, dressed in black silk with a brocaded bodice and a substantial white ruff and “records her features with objectivity and with a blunt, vigorous brushwork that seems in itself to reflect her character.”[11]

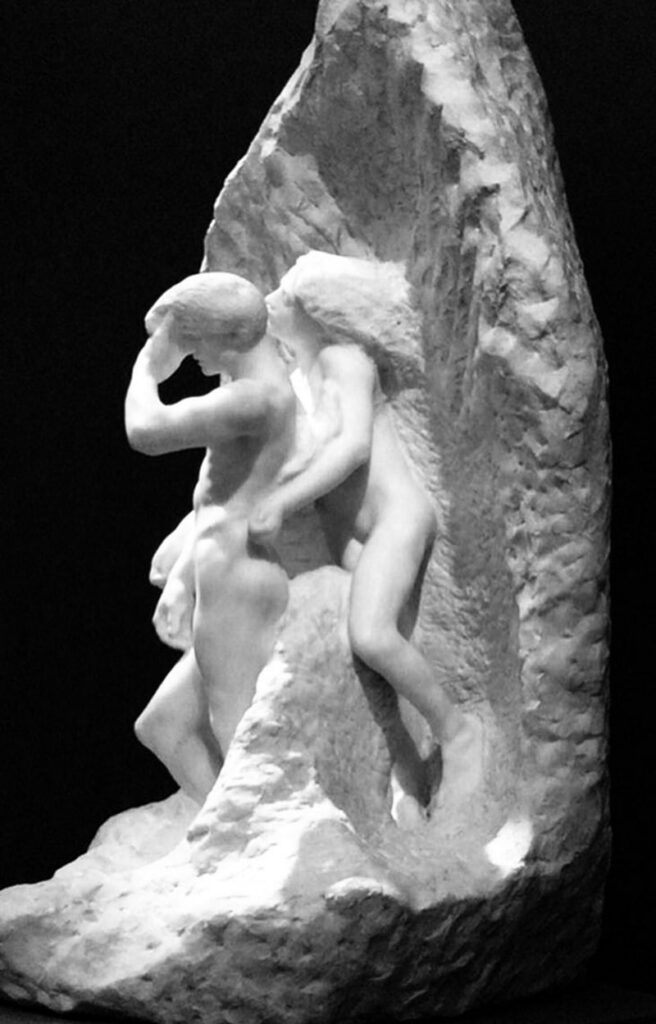

Auguste Rodin’s marble sculpture Orpheus and Eurydice (1893), now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was one of a pair of sculptures that, purchased by Yerkes, were the first of the sculptor’s work to find a home in the United States.[12] Depicting the bard Orpheus and his wife Eurydice walking out of hell, one behind the other, it is a “dramatic depiction of human grief [that] touches the heart of bereavement….”[13]

From Malibu to Boston

These masterpieces are among more than a dozen paintings and sculptures that were once owned by Yerkes and now reside in the collections of art museums from Malibu to Boston to Washington, D.C. Here are some others:

- Bacchante and Infant Faun, bronze sculpture by Frederick William MacMonnies (1901), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts;

- Cupid and Psyche, marble sculpture by Auguste Rodin (about 1893), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York;

- Diana, bronze sculpture by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1782), The Huntington Library, San Mateo, California;

- Mills at Dordrecht, painting by Charles François Daubigny (1872), Detroit Institute of Arts;

- The Music Lesson, painting by Gerard ter Borch (1665–1675), The Art Institute of Chicago;

- Philemon and Baucis, painting by Rembrandt van Rijn (1658), National Gallery of Art, Washington, District of Columbia;

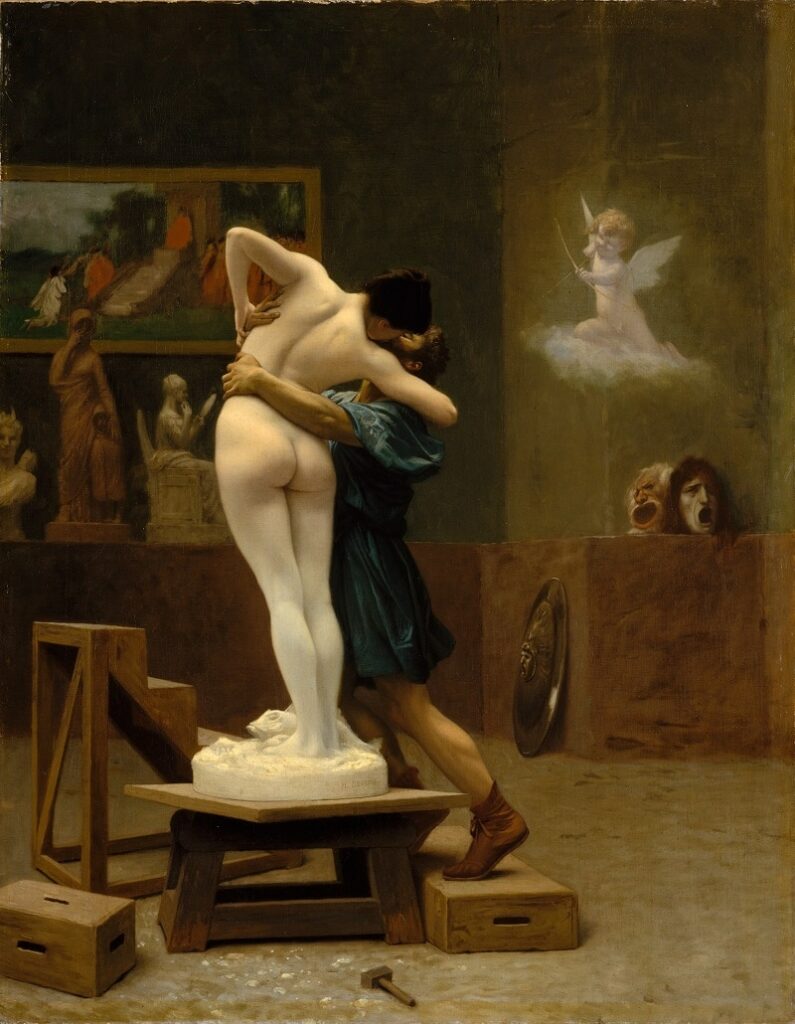

- Pygmalion and Galatea, painting by Jean-Leon Gerome (1890), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York;

- Pygmalion and Galatea, sculpture by Jean-Leon Gerome (1893), Hearst Castle, San Simeon, California;

- Spring, painting by Lawrence Alda-Tadema (1894), J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California;

- Valley of Tiffauge, painting by Theodore Rousseau (1837-44), Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio;

Although over-shadowed by such connoisseurs as Henry Clay Frick and Isabella Stewart Gardner, Yerkes was not only the first American collector to own sculptures of Auguste Rodin, but also the first to buy a signed history painting by Rembrandt van Rijn and the first, in 1893, to publish a catalogue of his collection with images and information about each of the artworks.[14]

During his years in Chicago, local newspapers gave significant coverage to his art holdings,[15] and, after Yerkes died in 1905, the New York Times devoted several days of front-page stories to the auction of his collection, calling it “the biggest art sale that America [had] known” up to that point, netting $2.2 million, the equivalent of about $68 million in 2021.[16]

Yerkes’s 21st century biographer John Franch devotes four pages to his subject’s art collection, a substantial amount considering the absence of any attention to it for a century. Nonetheless, Franch’s well-researched account is overshadowed by his book’s emphasis on the venality of Yerkes, as evidenced by its title Robber Baron. In my book about the elevated Loop that Yerkes brought into existence, I give only five paragraphs to his art. [17]

Yet, it is important to spotlight and detail this aspect of the financier’s life because he was a key figure in the American art world and continues to exert an influence today with the presence of so many of his holdings now in American museums.

A more rounded portrayal

In addition, his art collecting gives a more rounded portrayal of this one-of-a-kind American businessman who, in his own time and for decades after, has been stereotyped as just another corrupt financier. Indeed, in 1893, one Austrian art expert considered the Yerkes collection “one of the most important private collections in the world.”[18]

Yerkes’s extensive holdings, displayed in galleries in his homes, also included the work of renowned artists such as Jean-Antoine Houdon, Jean-François Millet and Claude Monet. His collection of Asian rugs, often called Oriental rugs, was better than that of the Shah of Persia and won praise from eminent (and hard to please) art connoisseur Bernard Berenson.[19]

A swashbuckling entrepreneur, castigated by his myriad critics for his take-no-prisoners approach to making money, Yerkes had planned to use his extensive art collection as the foundation for a public museum in New York City — the Yerkes Galleries. He left instructions in his will to make that happen. But, as had often occurred during his life, he was financially over-extended at the time of his death. To pay his debts, his art was auctioned off in one of the major American art events of the early 20th century.

He had hoped that Yerkes Galleries would be his legacy.[20] Instead, it was the London Tube — and, even more, Chicago’s elevated railroad Loop.

Eclectic and somewhat unsophisticated

When it came to collecting art, Yerkes wasn’t in the class of Frick and Gardner. They each had a better eye for art than Yerkes did and better advisors. They had more money, too. The institutions they created — the Frick Collection in New York and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston — are among the best in the world in their wealth of Old Masters.

And Yerkes wasn’t part of the crowd of Chicago collectors, led by Potter and Bertha Palmer, who were snapping up Impressionist paintings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries although he did own Claude Monet’s wispy Highlands on the Coast (1884).

In his purchases, he was eclectic and somewhat unsophisticated. Like many American collectors of the period, he bought his share of “Old Masters” later determined to be the work of other artists as well as his share of forgeries.

Nonetheless, art historian Walter Liedtke praises “the diversity and overall importance of the collection,” noting that it included “many pictures of exceptional quality not only [from Dutch and Flemish painters] but in the modern section and especially among the eighteenth-century French, English, and Italian paintings. A respectable effort was also made to illustrate early Northern and Italian Renaissance art.”[21]

Mara’s bright robes

Yerkes’ drive to acquire art had several sources, one of which was an ultimately futile hope of finding acceptance by Chicago’s and New York’s high society.

Born a Quaker and the son of a bank president, Yerkes found himself in prison in his early thirties. He had been riding high as a dealer in municipal securities in Philadelphia when his hometown stock exchange was struck by a panic that had been sparked by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. City officials demanded that he come up with the money he had received as the municipal bond agent, and, when he couldn’t find enough cash, he ended up convicted of embezzlement.

Although sentenced to two years and nine months in prison, Yerkes served only seven months before being freed by Governor John W. Geary on September 27, 1872. Some saw this as an acknowledgement that his conviction had been a miscarriage of justice, but others suggested that Yerkes had used bribery or blackmail to buy his freedom. As Franch details, it was the result of a directive from President Ulysses S. Grant who wanted to protect a political ally on the edges of the scandal.[22]

Yerkes was able to recover financially from his stay in the penitentiary — he soon announced he was again a millionaire — but his reputation was tainted from then on.

It didn’t help that the wives of the upper crust of Philadelphia society wanted nothing to do with him. Not only was he a convicted criminal, but he had walked out on his wife Susanna and their two surviving children to marry, in late 1881, the 23-year-old daughter of a wealthy local chemist, Mary Adelaide Moore, called Mara.

The new couple settled in Chicago, but they still found themselves ostracized, as Wesley Towner writes in his history of American art collecting:

Mara’s bright robes and illumined face failed to captivate the butchers’ wives of Chicago. Her fish-scale sequins and lime-colored velvet togas, her strident sensuality, her trailing plumes and outrageous feathers were intriguing to their golden husbands, but the social climbers of the Middle West were themselves too insecure to accept a bird of paradise within their midst.[23]

It was no different when Yerkes and his wife moved to New York City. The storied Four Hundred of high society, led by the Astors and Vanderbilts, turned their backs on the couple — although they did come out in force for the 1910 auction to pick through the Yerkes art holdings in search of bargains. Towner described it “the sacking of the Yerkes palace.”[24]

Competition

In addition to bringing prestige, art collecting is also a competition, and Yerkes loved to compete and win.

In his financial dealings, he was a high-stakes gambler, courageous and fierce. Indeed, Lyman Gage, a Chicago reformer and banker who served as U.S. Treasury Secretary, once said that Yerkes had “the heart of a Numidian lion.”[25]

Throughout much of his career, Yerkes’ key financial backers included Peter A.B. Widener and William L. Elkins, the Philadelphia “Traction Twins” who were instrumental in the establishment of that city’s streetcar system and invested in transit systems in Chicago and other cities.[26]

Both were art collectors, and both of their collections were bequeathed by their sons to the public. George W. Elkins left his father’s art to the city of Philadelphia in 1919. Joseph E. Widener, working with banker-philanthropist Andrew Mellon, helped establish the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., by donating his father’s collection in 1942, just a year and a half after the opening of the museum. (One painting in the Widener collection that went to the National Gallery was Rembrandt’s 1658 Philemon and Baucis which, earlier, had belonged to Yerkes.)

Of the three rivals, Yerkes made a bigger splash in the art world, partly because of his notoriety as an “impossibly corrupt” businessman.[27] But what particularly impressed his contemporaries was how quickly he amassed an art collection of such high caliber, numbering ultimately more than 200 paintings and sculptures.

In 1895, only six years after Yerkes began his art buying, his home gallery was praised by a British writer as being “quite fit to rank with most of the larger European private collections.” [28] Later, after the magnate’s death, influential art critic M. H. Spielmann wrote:

Mr. Yerkes took an enormous pride in the formation of this collection, and it may be questioned whether anyone, even a millionaire, has ever brought together a series so rich — alike as to quality and numbers — in so amazingly short a time…[29]

How to buy a work of art

Spielmann, who often ran into Yerkes in Paris during the financier’s summer buying sprees, admired his courtesy, lightheartedness, business methods and quick decisions. Although Yerkes received a lot of good and bad advice from various people in the art world, the Chicago magnate, it seems, made most of his own decisions.

He once told a reporter that buying a work of art involved the same wooing process as that used in the purchase a transportation company:

Well, when you go abroad and see a picture you think you would like to buy, the process of getting it takes a long time. You first send your card to the owner of the picture and he calls on you at your hotel. Then he invites you to make a call at his home and become acquainted with his family. They are all there and you make a long call and perhaps refreshments are passed.

The next day you will go there, and at this visit, if you are rash, you will casually ask the man if he wants to sell the picture which you have seen and admired. The man will look grieved, and as you leave he will tell you to call again.

On the occasion of your next visit the man may have communicated your wish to the other members of his family and you will be received a little differently. Each one in the family will have something to say about the picture and there may be a little weeping on the part of some of them. You won’t think, while on this call, of mentioning a price for the picture, but perhaps when you make your next call you may suggest the value of it to you. Finally, if you are patient you will secure the picture.[30]

So significant was the Yerkes collection that the 1910 auction of his art in New York was said to have “placed America in the very front rank of art-understanding countries.” [31] Not only was it the richest sale of art that had ever taken place in the United States, but it set the record — three times in two days — for the highest price paid at a public sale in America.[32]

The previous champion had been Constant Troyon’s Recour a la Ferme (Return to the Farm), also known as Vaches Alient au Champ (Cows Going to the Field), which sold for $65,000 at a New York auction in 1907.

But, on the second day of the Yerkes auction, the Troyon was unseated by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s The Fisherman for which the Duveen Brothers art firm bid $80,500. Then, later in the day, The Fisherman itself was vanquished by Turner’s “Rockets and Blue Lights” which was purchased also by the Duveen Brothers for $129,000.

The Turner’s time at the top, however, lasted just 24 hours. The next day, the winning bid for Hals’ Portrait of a Woman was from the art dealer M. Knoedler & Co. — $137,000, the equivalent of about $4.2 million in 2021 dollars. (Four days later, the painting was privately sold to Henry Clay Frick for his collection.)

Many of the Yerkes artworks ended up in private hands and remain there today. For instance, Jean Baptiste Camille Corot’s Morning (now known as Le Batelier passant derrier les Arbres de la Rive) was purchased by Howard McCormick[33] for $52,100 and later owned by George Walbridge Perkins, an assistant U.S. Secretary of State for European Affairs. In 1997, it was sold by Christie’s auction house to an unidentified private collector for $2,037,500, the equivalent of nearly $3.5 million in 2021.

His “true self”

Yerkes bought works of art in such a wide range of styles, schools and periods that many observers were confused by what appeared to be the unfocused nature of his purchases. But Spielmann wrote:

The fact is, that he was not buying for his own taste or aesthetic pleasure, of which he had not much, and that not necessarily catholic; his aim was to acquire good, if possible superlative, examples of all schools, with the ultimate object of making them the nucleus, or else the reinforcement, of the American national gallery…[34]

Spielmann was certainly right about Yerkes’ aim to use his art to create a museum, but his assertion that the mogul had no taste and derived no aesthetic pleasure from the enterprise seems misguided.

According to Franch, Yerkes saw himself as two persons. One was the warrior who, “cold, austere, and unapproachable during business hours,” cut a huge swath through the merciless jungle of commerce.[35] The other was a man of refined tastes, a lover of beauty — his “true self.” And Yerkes wanted his two worlds kept far apart. As he told one reporter:

I can not impress upon you too much the difference between the home and the office life of a business man. For example, I love pictures, but when a man comes here [to his office] to show me a picture, it provokes me. If he insists upon seeing me I usually find some reason for not taking what he has to offer.

But if the same man comes to my house I will sit up and talk pictures with him until 2 o’clock in the morning. I always throw aside business cares the moment I am away from business.[36]

For Yerkes, art collecting wasn’t just another competitive endeavor or a vehicle for breaking into high society. Above all, it made it possible for him to surround himself with beauty. “Art,” writes Franch, “gave meaning to the businessman’s life.” [37] It was, for him, a kind of religion, as a writer in the Town Topics magazine noted two months after Yerkes’s death:

[The love of the beautiful] was to him what religion is, a prayer of the heart. In building his home on Fifth Avenue [in New York] he built himself a chapel, an altar, where he could shut out the world and live in this religion — uplift his soul from the corduroy road of his financial life. There was not a nook or corner in his palatial home that was not sacred to him, something that was not sacred to this worship of his for the beautiful, sacred to his idea of the beautiful…something that answered the prayer of the soul of which the outside world knew nothing.[38]

Indeed, Harriet Monroe, the founder of Poetry magazine, wrote that she “liked and trusted the man.”[39] She knew the magnate in the 1890s when she was in her 30s, and called him “always a strange combination of guile and glamour, thrilling with power like a steel spring, loving beauty as a Mazda lamp[40] loves the switch that lights it.”

“Forbidden fruit”

Yerkes’ love of beauty in art extended to beautiful young women, and they reciprocated.

Yerkes had divorced his first wife to wed Mara, but he was, like many wealthy men of his era (and probably most eras), far from faithful to her. In fact, according to his right-hand man DeLancey Louderback, Yerkes had so many mistresses throughout his life that he had a set routine that he employed when he was ready to drop one:

[Yerkes was] frequently annoyed legally, and otherwise by discarded women, who wanted to hang on, and extort money from him. He generally broke with them in a nice way and continued to have their kind regard. When he found one otherwise, he managed to have someone else ingratiate themselves in with them, at his expense, and when exposed, he would brow beat them, and threaten to show them up as blackmailers, and always got the best of them, in the end. Money was no object in such matters, either to defeat an enemy or secure what he desired. [41]

Yerkes’ attitude toward young women was: “God bless them all.”[42] And his art collection reflected that. Indeed, it’s no wonder that he was the first American to buy Rodin sensual sculptures and bring them to the United States.

It happened this way: For the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, local art curator and advisor Sarah Tyson Hallowell worked closely with Bertha Palmer to organize an exhibit of foreign masterpieces from American collections for display in the Fine Arts Building. She wanted to include works by Rodin, but no Americans had any. So she wrote to the artist with this suggestion:

“Could you give me four or five works? I shall inscribe them in the catalogue as being in the collection of an American whose name I shall make up. I think this is legitimate because it is monstrous that so far there is not a single work of yours in our country!”[43]

He sent three works, all erotic nudes, one of which, titled Sphinx, featured a kneeling, sinuously twisting female figure. After only a week on display, the sculptures were removed from the hall, having been judged too lascivious. To see them, a fair visitor had to ask special permission.

Thus [writes Rodin biographer Ruth Butler] Rodin entered the American consciousness with a special flavor attached to his name. Yerkes, stimulated by the flavor of forbidden fruit, ordered two large marbles, Cupid and Psyche and Orpheus and Eurydice, for his Michigan Avenue mansion.[44]

It’s unlikely that Yerkes was a hard sell. “Forbidden fruit” was already a mainstay of his collection which ultimately included at least 19 nudes. Indeed, flanking the grand staircase of his New York mansion were two large slinky nude sculptures, one of which was the copy of a work that had been banned in Boston.

“Wildly erotic”

In 1892, a year before Yerkes bought the Rodin marbles, he commissioned the French academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau to create Invasion of Cupid’s Realm, also called The Wasp’s Nest, a work that was centered on the large breasts of a woman naked to the hips, fighting off seven nude cherubim.

One later writer calls it “wildly erotic,”[45] while another describes it as “better situated in a brothel.” [46] Nonetheless, unlike the three Rodin marbles, the painting, on loan from Yerkes, was displayed in a prominent place in the French Section of the Art Palace at the 1893 World’s Fair without controversy.

In his home gallery, Yerkes’ nudes were hard to miss. He had large fleshy nudes by Peter Paul Rubens in the 44-square-foot Ixion and Hera and a towering nude Diana as a huntress by Jean-Antoine Houdon that stood nearly seven-feet-tall and weighed 747 pounds. In Jean-Francois Millet’s Diana Resting, the goddess was sprawled voluptuously on her back on a riverbank, naked except for a strategically draped bit of gauzy cloth.

Another seven-footer was the dancing, intoxicated drunk girl, holding an infant faun and a bunch of grapes, in Frederick MacMonnies’ Bacchante, a replica of the bronze that had scandalized Boston. That was no wonder, considering this description by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York:

“An exuberant pagan reveler with grapes in her raised right hand holds an eager infant in the crook of her left arm. Her twinkling eyes, joyous mouth, spiraling form, lively silhouette, and richly textured surface combine to produce one of the most vibrant images in American art.”[47]

The original had been given by the artist to architect Charles F. McKim for display in the courtyard of the Boston Public Library, designed by McKim’s firm for Copley Square. But Temperance leaders and other Bostonians howled in protest at the “drunken indecency” of the statue, and McKim took it back and presented it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

A copy was made for Yerkes in 1901. And, today, that copy of the once-shocking sculpture is on display in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the city having gotten over its initial discomfiture.

“Her flesh a living satin”

Yerkes, the hard-driving financial wheeler-dealer and urban visionary, had a special liking for fleshy, erotic art by great artists, and the composition that seems most likely to have been his favorite was by Jean-Leon Gerome. Indeed, Yerkes liked it so much that he had two versions of it — one as a painting and the other as a sculpture.

Called Pygmalion and Galatea, the image is based on a story about the statue of a nude woman that comes to life when the sculptor doing the carving gives her stone cheek a kiss.

Describing the painting in a review of the Yerkes collection for the London-based Magazine of Art, F.C. Stephens wrote, “[T]he marble maiden blooming into life…glows from the breast upwards and downwards.” Her feet and lower legs are still marble, but, in her upper body, “her flesh [is] already a living satin.”[48] The work, roughly three feet by two feet, is now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Much more imposing is the life-size white marble sculpture by Gerome, more than six feet tall, purchased by Yerkes from the artist in 1893.[49]

Following the magnate’s death, the piece eventually ended up in the art collection of newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, a man who, as one of the founders of yellow journalism, was as demonized as Yerkes and whose life had many similarities to that of the entrepreneur. The sculpture can be seen today at the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California.

In collecting art, Charles Tyson Yerkes was expressing what was an essential element of his complicated and multi-faceted personality. While he was hoping that his collection would be his legacy, he was acquiring hundreds of beautiful artworks primarily for his own enjoyment.

Any attempt to understand the financier and all that he accomplished in Chicago and London must take this aspect of his character into consideration.

He has been often vilified and disparaged as simply a greedy tycoon. Yet, in his work in both major world cities, he showed himself to be an inspired city-shaper. And, in his art collection, he showed himself to be a man who, as Harriet Monroe wrote, loved “beauty as a Mazda lamp loves the switch that lights it.”

[1] The comments from the reviews by Sebastian Smee and Rachel Campbell-Johnston are quoted in Edmund Rucinski, “J.M W. Turner’s Rockets and Blue Lights,” at Artwatch International Inc., http://artwatch.org.uk/tag/turner-rockets-and-blue-lights/, accessed August 31, 2021.

[2] Edwin Lefevre, “What Availith It?,” Everybody’s Magazine, June, 1911, 841.

[3] Wesley Towner, The Elegant Auctioneers (Hill & Wang, 1970), 237. Lefevre, “What Availith It?,” 841.

[4] Wayne Andrews, Battle for Chicago (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1946), 176; Benson Bobrick, Labyrinths of Iron: A History of the World’s Subways (Newsweek Books, 1981), 112; Tim Sherwood, Charles Tyson Yerkes: The Traction King of London (Tempus, 2008), 26; Mario D’Eramo, The Pig and the Skyscraper: Chicago: A History of Our Future (Verso, 2002), 103; and Chicago transportation writer F.K. Plous, quoted in Sherwood, Charles Tyson Yerkes, 9.

[5] Patrick T. Reardon, The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago, (Southern Illinois University Press, 2020).

[6] Portrait of Joris de Caullery is imposing, in part, because it is so large, roughly three feet by three feet, and that size apparently saved it from thieves who, on Christmas Day, 1978, dropped through a skylight into the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, one of the two branches of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. They got away with a Rembrandt and other 17th century paintings and wanted to take the Joris as well but couldn’t fit it through the skylight. More than 20 years later, the paintings were returned. Subsequently, the stolen Rembrandt was judged not to be by the master. See “$1 million theft of a Rembrandt,” Chicago Tribune, December 26, 1978, 2, and John Kifner, “3 Masterworks Stolen in ’78 Are Mysteriously Returned,” New York Times, November 12, 1999, B5.

[7] George S. Keyes, “Rembrandt Paintings and America,” Rembrandt in America: Collecting and Connoisseurship, edited by George S. Keyes, Tom Rassieur and Dennis P. Weller (Skira Rizzoli, 2011), 70.

[8] In addition to the art gallery, the mansion also featured a gymnasium on one of its upper floors “fitted up with all the appliances of an athletic club.” Yerkes’s rotund figure may have suggested that his was a sedentary life, but the Chicago Tribune described him as “an athlete and a lover of manly sport, whether it be boxing, gymnastics, baseball or football.” Indeed, he spent an hour each day working out in the gymnasium. “Dumbbells were his workout tools of choice until 1895, when he became a self-confessed ‘bicycle crank,’ ” writes his biographer John Franch. See “The Fine Arts,” Chicago Tribune, July 17, 1892, 36; “Yerkes and His Gloves: Cable Magnate Polishes Off a Guest in His Michigan Avenue Gymnasium,” Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1894, 23; and John Franch, Robber Baron (University of Illinois Press, 2006), 201.

[9] Hylton A. Thomas, “View of the Grand Canal by Francesco Guardi,” The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin 46, no. 4 (Winter, 1957): 53-65, http://www.artsconnected.org/resource/94362/view-of-the-grand-canal-by-francesco-guardi , accessed May 11, 2015, no longer available.

[10] Emil Becker, “A Critique of the Yerkes Collection,” Fine Arts Journal, May, 1910, 220.

[11] Paintings from The Frick Collection, text by Bernice Davidson, Edgar Munhalf and Nadia Tscherny (Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York), 55.

[12] Franch, Robber Baron, 208.

[13] Douglas J. Davies, Death, Ritual and Belief (Continuum, London and New York, 2002), 200-201.

[14] Dennis P. Weller, “Rembrandt’s History Paintings in America,” Rembrandt in America: Collecting and Connoisseurship, edited by George S. Keyes, Tom Rassieur and Dennis P. Weller (Skira Rizzoli, 2011), 148; and Keyes, “Rembrandt Paintings and America,” 65. Although Weller notes that, in 1893, Yerkes became the first American with a history painting signed by Rembrandt, Keyes points out that at least one other indisputable Rembrandt painting Portrait of Herman Doomer had been purchased by the American art dealer William Schaus nine years earlier from the French duke Charles-Auguste de Morny.

[15] See, for instance, “From the Old Masters: Rare Collection of Paintings in Mr. Yerkes’ Gallery,” Chicago Tribune, November 30, 1890, 9, and “The Fine Arts,” Chicago Tribune, November 12, 1893, 34.

[16] “$2,034,450 Paid for Yerkes Treasures,” New York Times, April 9, 1910, 1. The total was increased over the next few days. See “$1,500 for Cromwell Sword: Weapon Dated 1650 Brings Top Prize at Yerkes Sale — Total Returns: $2,207,866,” New York Times, April 14, 1910, 6. The New York Times page-one coverage of the sale extended from April 6, 1910 through April 9, 1910, and was followed by other stories on inside pages on April 13-14, 1910.

[17] Franch, Robber Baron, 206-209, and Reardon, Loop, 91-94.

[18] “The Fine Arts,” Chicago Tribune, November 12, 1893, 34

[19] See Franch, Robber Baron, 208, and Sidney L. Roberts, “Portrait of a Robber Baron: Charles T. Yerkes,” The Business History Review, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Autumn, 1961), 347.

[20] Franch, Robber Baron, 322-323. In his will, Yerkes also set aside money to pay for a hospital in the Bronx. Like the Yerkes Galleries, the hospital was the victim of the mogul’s great debts.

[21] Walter Liedtke, “Dutch Paintings in America: The Collectors and Their Ideals,” in Ben Broos, Great Dutch Paintings from America (Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, 1990), 37-38.

[22] Franch, Robber Baron, 70-77.

[23] Towner, The Elegant Auctioneers, 197.

[24] Towner, The Elegant Auctioneers, 237.

[25] “Lefevre, “What Availith It?,” 839. Slaying the vicious Numidian lion, also called the Nemean lion, was the first of Hercules’ twelve labors in Greek mythology. Before the hero was able to strangle the beast, the lion bit off one of Hercules’ fingers.

[26] “William L. Elkins Dead,” New York Times, November 8, 1903, 1.

[27] Liedtke, “Dutch Paintings in America,” 38.

[28] F. G. Stephens, “Mr. Yerkes’ Collection at Chicago,” The Magazine of Art (Cassell and Co., 1895), 96.

[29] M. H. Spielmann, “The Yerkes Collection,” The Art Journal (William Clowes and Sons, 1910), 110-111.

[30] “Wall Street A Will-O’-The-Wisp,” Chicago Tribune, November 3, 1899, 1.

[31] J.P. Morgan’s lawyer John G. Johnson, quoted in Liedtke, “Dutch Paintings in America,” 38.

[32] See “Troyon Brings $65,000 at American Art Sale,” New York Times, January 26, 1907, 9; “43 Yerkes Pictures Sold for $769,200,” New York Times, April 7, 1910, 1; and “$137,000 for a Hals at the Yerkes Sale,” New York Times, April 8, 1910, 1.

[33] It is possible that the buyer was L. Hamilton McCormick, a Chicagoan and member of the wealthy McCormick family, and the name was misreported. There does not appear to have been a prominent art collector named Howard McCormick.

[34] M. H. Spielmann, “The Yerkes Collection,” The Art Journal (William Clowes and Sons, 1910), 111.

[35] Franch, Robber Baron, 205.

[36] Quoted in Franch, Robber Baron, 201.

[37] Franch, Robber Baron, 209.

[38] Town Topics, March 1, 1906, 15, quoted in Franch, Robber Baron, 209.

[39] Harriet Monroe, A Poet’s Life: Seventy Years in a Changing World (AMS Press, 1930), 117.

[40] Mazda was a brand name of a General Electric incandescent light bulb.

[41] Franch, Robber Baron, 212.

[42] Lefevre, “What Availith It?,” 840.

[43] Quoted in Ruth Butler, Rodin: The Shape of Genius (Yale University Press, 1993), 400.

[44] Butler, Rodin, 400.

[45] Franch, Robber Baron, 210.

[46] Towner, The Elegant Auctioneers, 195.

[47] “Bacchante and Infant Faun,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art website, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/97.19 , accessed August 31, 2021.

[48] Stephens, The Magazine of Art, 168.

[49] Gerome, Jean-Leon, Pygmalion et Galatee, French Sculpture Census, French sculpture 1500-1960 in North American public collections, https://www.frenchsculpture.org/index.php/Detail/objects/32258, accessed August 31, 2021.

…

Patrick T. Reardon

9.8.22

This article originally appeared in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 114, Numbers 3-4, Fall/Winter 2021.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.