Make no mistake about it. I love physical books. I love the weighty feel of a book in my hands. I love the aroma of a book when you open it whether a hardback, new from the publisher, or a musty old paperback that has simmered on some obscure shelf for decades. I love the way they line up, thick and thin, as neat rows of multi-colored spines, on my many bookshelves.

But, now, I find contemplating the coming death of the physical book.

The symptoms are many, and they include those cute little free libraries (which I love), the disappearance of most used bookstores, the preference of many readers for ebooks (“So easy to carry!”), and the cancellation of the annual Newberry Library book fair.

I never thought it would come to this. But, then, I never thought that a newspaper like the Chicago Tribune, where I worked for 32 years, would wither to a shell of itself, a minor player in the media world of news reporting.

This isn’t exactly an obituary for the physical book because libraries will continue to hold them, at least for a while. And some will be kept as family heirlooms or as quaint throwbacks to an earlier time. I wouldn’t be surprised if some printed books continue to be produced for a niche audience who have money to pay for an odd old technology and find a kind of cachet in it, the way that LP records are still around on the edges of entertainment merchandise.

Nonetheless, the physical book — the building block of my education and my entertainment and my work for decades — is no longer a building block for the 21st century world. The physical book, once a keystone of culture and society, is now fading away from significance and from relevance.

Think of the last time you were in the home of someone born after 1980. Were there bookshelves? Were there books? Or think of riding on a bus or in an airplane. How many people are reading a book? How many are looking at their electronic devices?

Anything a human could intellectually create

What we think of as a book dates back some two thousand years. Books have been a product for the masses since Johannes Gutenberg and his movable-type press went into operation around 1450.

Over those nearly seven centuries, the book has been an amazing piece of technology, an object that enabled the distribution of hundreds of thousands of words between two covers in an easily transportable form — an object that could transmit esoteric philosophy and ribald satire and fairy tales and virtually anything a human could intellectually create.

There are still some used bookstores around, but nothing like the scores that dotted the Chicago city and suburban landscape in the 1970s and 1980s. I used to haunt those stores, many of them hole-in-the-wall operations, looking for books by favorite authors or with subjects or titles to grab my interest.

One reason for the sharp drop in their number is competition from the Internet. But another is that people, increasingly, aren’t interested in a book they can hold in their hands. I know a good number of Baby Boomers who grew up reading books and are now opting for ebooks, and, if a Boomer isn’t reading a physical book, is someone from Gen X or Gen Z or Gen Alpha likely to pick one up?

Nowhere else for them to go

In the last week, there’s been a lot of cheeping and chirping about the decision of the Newberry Library to cancel its annual used book sale after 38 years. There are, apparently, a number of reasons behind this decision. It seems clear, however, that, if the sale were making money hand over fist every year, it would be continuing. The Newberry has decided that used books as a money-maker aren’t worth the trouble.

Other indications abound of society turning away from physical books, but, for me, the most telling one is the little free library a block away from my house down Paulina Street.

I’m a big fan of little free libraries, and I’ve written in their defense in the face of an effort by a Chicago alderman to tax them and limit their availability. They are a good way to promote reading and a good way to help the environment by keeping books away from the landfill.

However, the books that end up in that little free library on Paulina and all the other small book boxes I see in my walks around Uptown, Edgewater and Rogers Park are there because there’s nowhere else for them to go.

It used to be that you could sell your books to used bookstores or give them to charity book sales, such as the one run by the Newberry, but those opportunities have been drying up. What can you do with a book you no longer want?

A kind of intellectual community

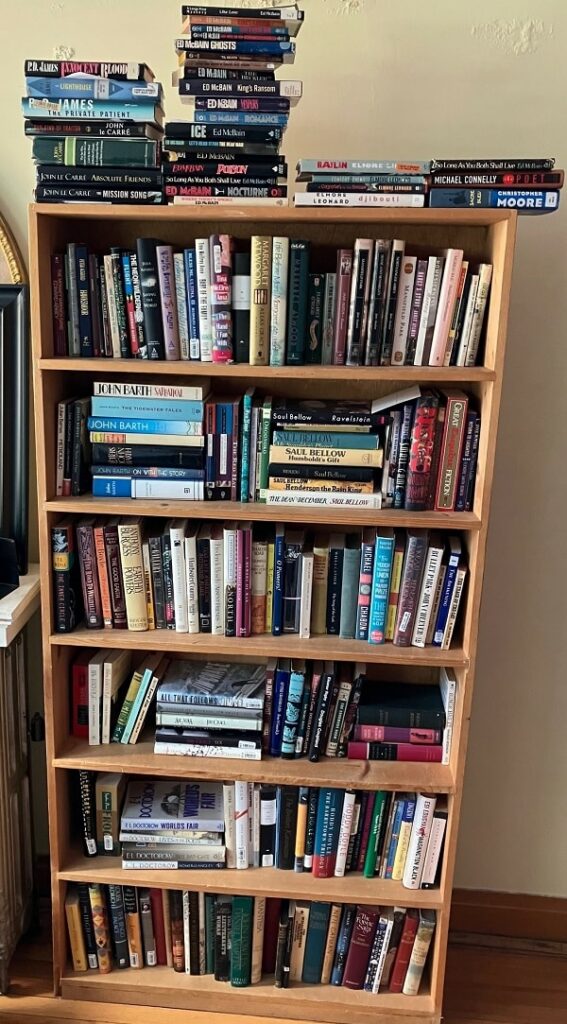

This hits close to home for me. I have a personal library of maybe five thousand books that have been a kind of intellectual community for me for half a century.

It includes an extensive collection of books about Chicago that I gathered as a Tribune reporter and later when I wrote The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Saved and Shaped Chicago. I have several bookshelves on religion and spirituality, and dozens with works of fiction and even more with works of history, biography and other non-fiction. I hold onto books that I read because I like to refer back to them, particularly the history books, and to re-read them.

Throughout the early decades of building my collection, I knew that, when it was time for me to dispose of the books, I could find a home or homes for them.

I figured there would be younger versions of myself who would find as much pleasure as I have from, say, my Chicago collection or perhaps my spirituality books. And, because, for the most part, the books are books of substantive research or of literary merit of perennial interest, I thought that bookstore owners would want them to resell. As late as 1995, I could have drawn up a list of stores that I was sure would want my books.

No home for these books

Now, I’m afraid there will be no home for these books. I can’t imagine, now, that there is any young person — anyone 40 and younger — who would want my Chicago books. Why take my copy of The Promised Land by Nicholas Lemann when you can get it as an ebook? Or my copy of The Saloon by Perry Duis or Don’t Cry, Scream by Don L. Lee (Haki Madhubuti)?

The number of places or charity sales that might be interested in at least some of the books is getting ever smaller, as the Newberry book fair demise shows.

I don’t want the physical book to go out of fashion, but that’s happening. I wish it weren’t so. It makes me sad.

Maybe this is an obituary after all.

Patrick T. Reardon

10.30.23

This essay initially appeared 10.27.23 at Third Coast Review.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.