I’m Catholic to the core. I lector at Mass. My kids went to twelve years of Catholic school. I know the smell of incense and the flickering of altar candles. I was an altar boy and, for a long while, thought I might become a priest. I believe in the Beatitudes and the Creed. I pay attention to the Pope, the bishops and the clergy — but not too much. I pay attention to the Dorothy Days of the world and of my parish. I’ve even roughed out a plan for the readings at my church funeral.

So why is it that, for a very long time, I’ve been captivated by a 1986 song by Van Morrison and by a scene in the 1993 movie Little Buddha?

The Morrison song, “In the Garden,” is from his album No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, a title that comes from the song’s key lyric. It’s a deeply spiritual song, but not in the way of organized religion.

“I turned to you”

For instance, the speaker in the song is a man talking with his female love, and, at one point, he says, “And we touched each other lightly/And we felt the presence of the Christ/Within in our hearts/In the garden.” It’s as if the Old Testament’s Song of Songs had found a place in the Gospels.

Then, the punchline: “And I turned to you and I said/No guru, no method, no teacher/Just you and I and Nature/and the Father in the garden.” He repeats this a second time, adding at the end, “And the Father and the/Son and the Holy Ghost.”

Few rock songs mention Jesus and the Trinity in the context of a romantic relationship. Yet, the involvement of God and nature in the couple’s love has nothing to do with institutional Christianity since the song and album insist, “No guru, no method, no teacher.”

That line grabbed me when I first heard it more than three decades ago. And it still does.

“No eye, no ear”

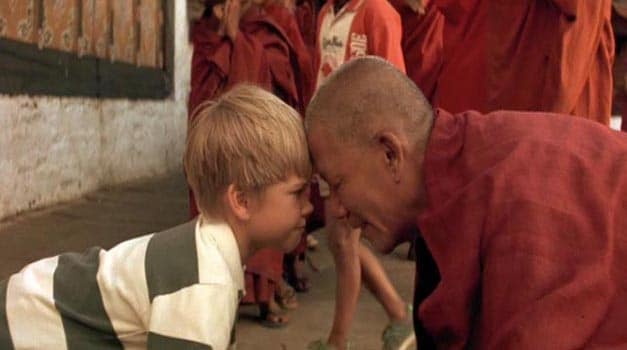

The scene in Little Buddha, probably the most spiritually inspiring movie I’ve ever seen, is similar.

The film is about a 10-year-old Seattle boy, Jesse Konrad, one of three children from different places around the world who have been identified by Buddhist monks as the reincarnation of one of their great teachers. During a visit to a monastery in Bhutan, Jesse and the other two take part in a funeral ceremony for their own teacher Lama Norbu and see him in a vision.

Then, as the hauntingly beautiful score by Ryuichi Sakamoto swells in the background, Jesse turns to his father and joyfully says, “Lama Norbu just said: ‘No eye, no ear, no nose, no Jesse, no Lama! No you! No death and no fear!’ ”

Some people hear that and go, “What? What can it mean?” But the words hit me with such power and beauty that I get chills every time I see that scene — and I watch it often.

All these no’s

Why do these two works of art have such an impact on me? I’m not an opponent of organized religion. I’m not Buddhist. How can I reconcile all these “no’s” with all the yes’s I’ve said to Catholicism in my long life?

As best I can figure, it’s this: Life is deeply mysterious. Even as we’re born, we’re already dying. My belief in God doesn’t take that away. My membership in the Catholic Church and my living according to the teachings of Jesus and the Bible don’t take that away.

Van Morrision’s “No guru, no method, no teacher” — for me, that means that no human being and no set of human principles, directives, rules, guidelines, dogmas or procedures can erase that deepest of existential realities, the unavoidableness of death.

Death as the essential fact of life can only be faced fully through love, and that includes romantic love as well as the love that is in relationship with the natural world and the love that is called God.

Off to the side from logic

That, I think, is what I’m hearing when Morrison sings. And it dovetails, I believe, with Jesse’s words in Little Buddha’s climactic scene.

What I hear in those words is the recognition that we human beings and all of the Nature are part of the same fabric that is God. I’m sure whole gangs of theologians and philosophers could tell me why it’s illogical to think like that.

But what Jesse is saying rises above logic, or exists off to the side from logic, or occurs at some much deeper level than logic. There is something here, it seems to me, that gets at what Christian saints — indeed, all saints — experience.

When Jesse says those words, including “no death and no fear,” he’s not saying that death doesn’t occur and that fear doesn’t happen. He’s saying that, on a deeper level, when I die, I don’t die. I am, in some way, part of all that God had created, and I will continue even after my body gives up the ghost. This may call to mind the Christian concept of heaven, but it’s much broader than that, I think.

God’s fabric

I am a part of God’s fabric, no matter what. Nonetheless, I can get more in tune with that reality and I can get closer to feeling whole if I open myself to others, to the natural world, to God — to be open and surrender and accept.

God has woven me into the Universe. I can try to ignore that, but I’m still part of the warp and woof of the cloth. Or I can try to get quiet enough, to get vulnerable enough, to get humble enough to see myself as a thread among the billions and trillions of threads in the cloth that is the Universe and is God.

The Van Morrison song and the scene from Little Buddha urge me to be comfortable in my place in God’s fabric. At a deeper level than any method or any Lama or any fear, they remind me that I am with God and God is with me.

Patrick T. Reardon

7.6.21

This essay originally appeared in the National Catholic Reporter 5.29.21.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.