I was asked by the Chicago Literary Club, a very old social organization in the city — now in its 149th season — to give the Arthur Baer Fellowship Address on December 12.

When Dan Pyne, the immediate past president, invited me, I was honored but a bit unsure what to talk about. Dan said I could just read from something I’d already written, and I thought: How about from three somethings?

The title for my talk is “Reporting History: How to look at Chicago and, well, at all of humanity as a reporter, historian and poet.”

“Reporting History.” When I say “reporting,” I mean going in search of the truth — actually the closest approximation of it — and coming back to report to others about what I’ve found.

When I say “history,” I mean the entire arc of life from past through present to future.

This is the context in which I have done my work throughout my entire writing career — as a newspaper reporter, as a historian and as a poet.

I’ve been writing for more than half a century, starting with my first byline at the age of 12 in the Garfieldean newspaper on the West Side in June, 1962.

Ten years later, I started my professional career and worked as a reporter from 1972 through 2009 — 37 years, 32 of them at the Chicago Tribune.

Throughout my time at the Tribune, I had a special focus on urban affairs in all its many facets, including neighborhoods, development, politics, demographics, race, faith, housing, schools and nature. For the second half of my Tribune time, I also covered the book industry, interviewing such writers as Robert Caro, Richard Russo, Patrick O’Brian, P.D. James, Ishmael Reed, Danielle Steel, John Keegan, Haki Madhubuti and Sandra Cisneros. These interviews, some of them very extensive, were informal individual writing seminars for me with these very accomplished people.

Before and after my newspaper career, I did a lot of freelance work, and, in the mid-1990s, I began writing books.

I’ve authored twelve of them, including The Loop: The “L” Tracks That Shaped and Saved Chicago, three poetry collections and a memoir of my first year as a baby. I got a good amount of my poetry published in the 1970s in small magazines, and I’ve written even more over the last fifteen years.

With this talk, I’ll read from and comment on some slightly modified examples of “reporting history” as a reporter and as a historian and as a poet.

…..

“A Metaphor with a Roof”

On February 2, 1997, I had a story in the Chicago Tribune magazine, titled:

A METAPHOR WITH A ROOF

BUNGALOWS WERE BETTER THAN A PLACE TO LIVE

THEY TOLD THE WORLD WHO YOU WERE.

Here is how the article started:

———-

In Chicago, the bungalow is a state of mind — an idea, a symbol, a trophy, a style, an approach to life.

It is also the stolid, low-to-the-ground, single-family house, most often of brick, that has been the home of millions of Chicagoans and suburbanites over the last century. It’s a housing style that has helped define the city and, in its way, form Chicago.

Say the word: bungalow. It is a rare term, with its curious mix of vowels and its particular fit of consonants.

“It bounces out of the mouth and rolls off the tongue in a pleasant, happy sort of way,” according to one expert.

But the word can also be said with a smirk, as when architects dismiss the bungalow as “the least house for the most money.” And it can be said in derision, as when Woodrow Wilson belittled Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge’s ideas by calling him “bungalow-minded.”

In Chicago, it is a word heavy with meanings, and rarely treated with disdain.

One former bungalow resident told me:

“For most of us, living in a bungalow was a step up. It was like winning a medal. You had your own little lawn. You could plant your own tomatoes.”

Indeed, over the years the bungalow was home to so many Chicagoans that it has achieved the level of cultural icon, as important to the mental landscape of the city as it was to its physical geography.

When William Lipinski was in a heated congressional race against Marty Russo some time ago, he mailed to voters photos of his Southwest Side bungalow and of Russo’s Tudor-style home in the suburbs. The message was clear: Lipinski was a man of the people; Russo, in his non-bungalow, someone putting on airs.

It was not for nothing that Mayor Richard J. Daley made his home in a Bridgeport bungalow. Or that his son, Richard M., the family’s second mayor, lived in a similar home a few blocks away. It was only after four years of consolidating his power as mayor that Daley the son felt comfortable enough to move from Bridgeport to an upscale Central Station rowhouse not far from the lake.

There has always been a touch of innocence equated with bungalows in Chicago, something cocoon-like.

That’s what made the Schuessler-Peterson case so shocking in 1955. The three boys-14-year-old Robert Peterson and his friends, John and Anton Schuessler, 13 and 11-were from “good families.” You could tell that because they lived in a Northwest Side bungalow community. Their parents were solid citizens, as solid as those bungalows, not riffraff. So, when the boys disappeared and two days later their naked bodies were discovered in a forest preserve — they had been strangled — there was an acute sense of violation and even despair.

Chicago has two immense fields of bungalows, each with tens of thousands of them — one covering the entire Northwest Side of the city, the other blanketing the Far Southwest and South Sides, thick as prairie grasses once clothed the plains.

Mob boss Sam “Momo” Giancana lived in a bungalow, and it was in the basement kitchen of his bungalow in 1975 that he died, shot once in the mouth and five times in the neck.

But what a bungalow! Giancana’s home was a mansion-like bungalow. Sure, it was a one-story structure with bedrooms in the attic and a finished basement. But it sat massive and brooding — its interior opulently furnished — on a quiet side street at the south end of Oak Park. And it was the servants who lived in the attic.

The Chicago bungalow has come to mean so many things, to symbolize so much, because it is an amazingly nebulous form of architecture. (Giancana’s imposing home was as much a bungalow as the humblest stucco structure next to former farmhouses in the Chicago Lawn neighborhood.)

Bungalows can be found throughout the world, but few look like the squat, solid, fortress-like bungalows so ubiquitous in Chicago and its suburbs. Indeed, so many different types, styles, forms and sizes of housing have been called bungalows since the term first came into use 300 years ago that sociologist-historian Anthony D. King writes in “The Bungalow” (Oxford University Press), “For the purpose of this book, a bungalow is defined as a dwelling form known by the term ‘bungalow.’ “

The American bungalow craze started in California and spread throughout the nation during the first three decades of this century. While bungalows can be found today in virtually every corner of the country, nowhere are they more numerous than in Los Angeles and Chicago.

The California-style bungalow, which is often seen as the progenitor of all other mass-produced bungalows, is a one- or one-and-a-half-story structure, as much wide as long, on a large lot. A frame house with wood or stucco siding, it usually features an open-air porch where family members can enjoy the cool of an evening in the balmy California climate.

The Chicago bungalow is a much different animal — sturdier and more self-contained, more rooted, less flighty. The weather, of course, is part of the explanation. The Chicago bungalow is faced with brick, the better to withstand Midwestern winters. Its front porch is often purely vestigial, just a simple landing where a visitor can stand out of the rain or snow while waiting for someone to answer the door. Inside, as a buffer between the weather and the living space, there is a vestibule where coats and boots are put on or taken off.

And it is built on a long, narrow lot, often no wider than 35 feet. Its eaves can’t project too far out on the side without hitting the bungalow next door. So, by necessity, it has to be more rectangular in character. But, as a consolation prize, the Chicago bungalow, unlike its California cousin, has a full basement — in fact, a lower-level second story, often with a kitchen-to provide additional living space.

The golden age of bungalow construction in Chicago was the decade following World War I; some 100,000 were erected in the city and Cook County suburbs. Not only were soldiers returning from war, but European immigrants from earlier years were finally grabbing a toehold in the American economy, and young men and women were flocking to the city from farms, lured by jobs and the excitement of city life.

A severe housing shortage drove apartment rents through the roof, but, with more than half a million vacant lots in the city in 1921, the price of land remained low. Cheap land and cheap transportation — the extension of public transit out to the edges of the city and the proliferation of automobiles — set the stage for the bungalow boom that followed.

Many of the families who moved into the new bungalows were immigrant families who, after being cooped up in crowded apartments, were lusting for homes of their own.

“They were land-hungry,” said one expert. “Owning land would have made them almost nobility in the homeland, but they were able to afford it here on a mechanic’s salary.”

———-

There was a lot more in the story, but this gives you the essence of it.

I liked this piece when I first wrote it and have liked it ever since because it was a way for me to explain to Tribune readers something every Chicagoan knows about, the bungalow, but doesn’t think about too much.

What I was aiming to do was to weave together the many strands of the meaning of the bungalow in order to present a well-rounded picture, a picture that hadn’t been written before.

And it was a picture that showed not just a housing type but also provided a glimpse into Chicagoans and into the city where they live.

….

The Loop

That was what I was also trying to do in my book about Chicago’s elevated Loop and its impact on Chicago.

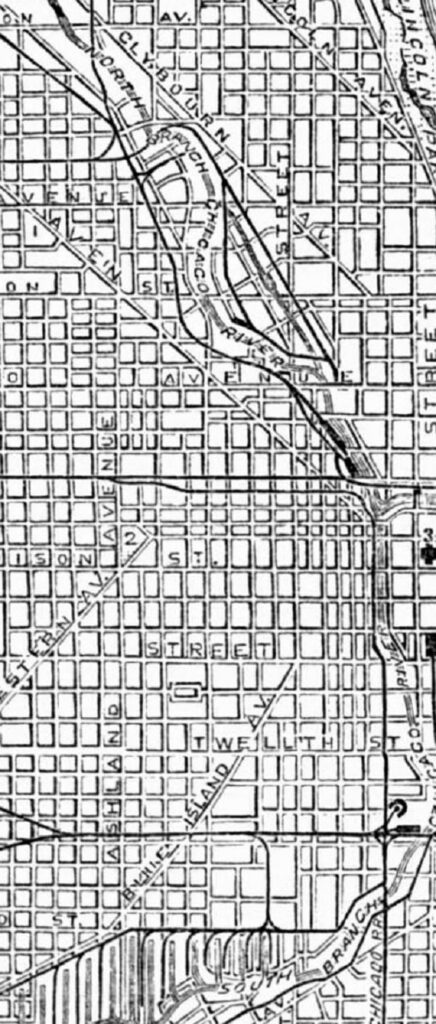

In my research, I discovered that the rectangle of elevated tracks was the most important structure in the history of Chicago.

Not only did the elevated Loop function as a key transportation link, making it possible to get from one distant end of the city to the other, but it also provided the city with a center that, more than any other place, belonged to ALL Chicagoans. In a city of divisions, the downtown area delineated by the elevated tracks became everyone’s second neighborhood in a way no other part of Chicago was.

Even more important, the elevated Loop gave its name to the downtown — a process that took 15 years — and anchored the most expensive land in the city in place. This made it possible for Chicago to survive the suburbanization of the 1960s and 1970s. So much money had been focused on the downtown by the elevated Loop that landowners couldn’t pick up and flee to the suburbs. They had to find a way to make the downtown continue to work.

All of that was new and revealing for readers, as was much of the rest of my book. One revelation was especially dear to my heart, and that was to tell the story of the larger-than-life engineer who was virtually unknown to Chicagoans but who designed the elevated Loop. And designed it in such a solid way that, today, 75 percent of the structure is original. That means — it’s 125 years old and still operating safely and efficiently.

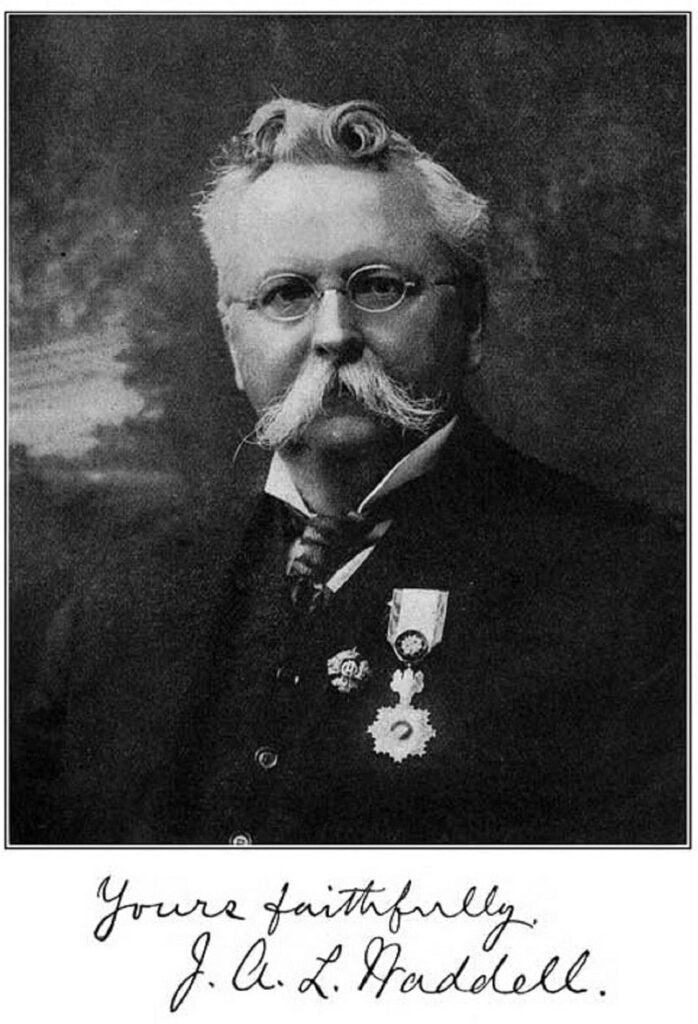

John Alexander Low Waddell

The guy’s name is John Alexander Low Waddell. And here’s how I start my chapter on him.

———-

A pamphlet, published in 1898 for the riders of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway, gave a detailed description of Chicago’s new Union Loop, noting it was “the clearing point for all elevated trains in the city.” And that was certainly true. Every day, more than 1,000 trains of the three (later four) elevated railroad companies, carrying an average of some 180,000 passengers, entered the downtown and then, after making the Union Loop circuit, headed out to the city’s neighborhoods again. Yet, the recently completed structure wasn’t just a means for smoothly and efficiently turning trains around.

Even more, the Union Loop was a rectangular bridge, linking together in an unprecedented way the three parts of Chicago — the South Side, the West Side and the North Side. Like a bridge — like the Brooklyn Bridge — the Union Loop was a connection. The Brooklyn Bridge took Brooklyn and Manhattan and, in joining them together, unified them and made them stronger. A decade and a half later, the elevated Loop took the three areas of Chicago, isolated from each other as they had long been, and broke down that isolation. Suddenly, it was easy and fast to travel from the farthest edges of one end of the city to the farthest edges at the other end.

The elevated Loop, in essence, transformed the individual elevated lines into a single network, and, in doing that, it transformed those three sections of the city into a unified whole, into a union. It was no happenstance that it was called the Union Loop.

Indeed, the various sections of the elevated Loop even look like bridges. That shouldn’t be a surprise since each was built by a bridge-building company. Not only that, but the main reason the four sections look like bridges is that they were designed by the internationally renowned bridge-builder John Alexander Low Waddell.

.

The year was 1882, and John Waddell, just making a name for himself as an American engineer, was taking his new wife, the former Ada Everett, from her home town of Council Bluffs, Iowa, to his new job on the other side of the world — to Tokyo. It was something of a honeymoon since they left shortly after their July 3 wedding.

The Japanese government, seeking to beef up the faculty of its newly established Imperial University of Tokyo, had hired the 28-year-old Waddell as the chairman of the civil engineering department. He looked forward to heading a large program but also expected to have time to do side jobs. Instead, he found that, during his four years in Japan, the department never had more than twelve students, and, as a foreigner, he couldn’t find any private engineering work.

Never one to loaf, Waddell used his extra time to write two books. The first was The Design of Ordinary Iron Highway Bridges, one of the few books published in that era about bridge-building. In fact, the book “became the seminal text at many engineering schools throughout the world, the ‘gold standard’ text on iron/steel bridge design.”

His second, A System of Iron Railroad Bridges for Japan, caused an uproar.

“I hope you will excuse me,” Waddell writes of his brash, blanket critique of Japanese bridges. Attempting to soften his harsh judgement, he tells the Japanese that it’s not their fault. “[T]he designs are not yours but are the work of some present and former foreign employees of the Railway Department.” The problem, as he sees it, is that these foreigners were English and not up to snuff to Americans.

Although this stirred up a hornet’s nest of controversy in Japan, Waddell was no shrinking violet and gave as much as he got. And, when he left, he did so with a medal from the Japanese emperor.

.

A thickly built man of medium height, John Alexander Low Waddell was “quite stately with his white hair [and] a long brushy moustache.” He was a fastidious dresser, and found great enjoyment in attending formal occasions with his hair ornately curled and, to the amusement of some of his colleagues, with many of his medals festooned on the chest of his tuxedo, including the Japanese Order of the Rising Sun. Waddell was a man “not known for his humility.”

He left his mark on Chicago, with an elevated railroad loop that is arguably the most distinctive visual element in the city’s downtown — and in any city’s central business district. With its airy steel framework and its looming presence over the cityscape and its trains rumbling 20 feet overhead, the elevated Loop says “Chicago” in a most physical and visceral way. But you won’t find Waddell’s name in a history of Chicago. And it’s a rare account of the city’s transit system and central business district that mentions him.

Throughout his 63 years as a civil engineer, he designed more than 1,000 bridges and other structures, but none more significant that the elevated railroad Loop in Chicago. None has been used by as many people on a daily basis for more than a century as his Union Loop. None has played as significant a role as a cultural force for unifying a city as his elevated Loop has for Chicago. Although often viewed in the past as the city’s ugly duckling, the Union Loop staked out and helped create and preserve the downtown common-ground shared by all Chicagoans. It has anchored Chicago’s central business district, enabling the downtown to withstand the storms of demographic, social and lifestyle shifts which have laid low many other municipalities.

Yet, when Waddell died in New York City on March 3, 1938 at the age of 84, his role in designing Chicago’s elevated railroad Loop more than four decades earlier was ignored.

Waddell was, the New York Times stated, “one of the leading bridge engineers of the United States.” In the Chicago Tribune, he was identified as the inventor of the modern vertical lift bridge. Neither newspaper mentioned his Union Loop.

———-

.

So, there you have, examples of “reporting history” as a reporter and as a historian.

Poetry?

How does poetry enter into the picture?

Well, poetry is a way of getting at a deeper sense of life that can’t be reached with logic and prose. Think of Allen Ginsberg’s long poem “Howl,” published in 1956. This poem was a way of talking about mid-20th century America by talking about what couldn’t be talked about, by thinking about what no one wanted to give thought to.

My poetry isn’t in Ginsberg’s class, but I’m also trying to capture a sense of what it means to be alive today, and often, in my poems, this involves what it means to be alive in Chicago today.

I’ve got three poems here from my 2021 book Darkness on the Face of the Deep. Unless you read a lot of poetry, they may seem like gibberish, but that’s OK.

Try to listen for images or ideas that strike you. You don’t need to understand the whole thing, but maybe, here and there, you can get glimpses of the Chicago I’m writing about.

Here goes:

Towers Loom

.

Loop towers loom behind their

gleam, and I can take you to the

parking lot just off Dearborn

Street where the Mayor and

reporters went down into

unflooded freight tunnels

(although that lot is likely gone

now, 26 years later).

.

Alex and I drove south to north

from city border to city border

through alleys of Chicago, world

alley capital. I saw a garage sale

chair and came back later to buy.

.

If you walk under the Loop and

follow the tracks west down Lake

Street — the soldierly tromp of

steel frames to oblivion — you

follow my brother’s walk as a

twelve-year-old through a Sunday

summer afternoon (through black

hot neighborhoods where young

men and old, grandmothers and

skip-ropers saw him as a gray

-dungareed shaman, magic blond

boy), up back stairs, to the

Leamington second floor, 52

years before self-murder.

.

Younger, he and I crawled

around the new-poured

foundation of a Washington

Boulevard building, so muddy

and our bikes, we had to walk

them home to the double-

spanking for the double of us

by Dad, on the porch, then

after the bath in bed.

.

Up Western from 79th Street, I

drove to Chicago (800 north)

and turned left, out to the

reporter job in Austin. A

right turn, and, in a mile,

Ashland, where, thirty

years later, I walked with

Sandra the grit Chicago that

abraded her out to the

southwest and Mexico and

back southwest again, talking

of the dust on medical

implements in the drug store

window, dowdy Rexall, and,

a decade later, my son and

his wife live there in a duplex

with two fireplaces and never

saw the Rexall, gone now.

They can walk to work in

the Loop in looming towers.

———-

City Hymn

Hymn the sewer line.

Hymn the rhythm.

Hymn mown grass,

dawn-sun broken glass,

ash tray brass,

my scar, the rusted-nail fall.

.

Hymn the sink hole.

Hymn girder.

Hymn cinder alley,

maggot alley,

the basketball-rimmed garage.

Hymn chaotic bloomed colors along the garbage fence.

The boy I am

studies in the concrete of my alley,

large smooth stones,

and seeks in their curves

answers to questions I don’t know to ask,

my inhale-exhale.

Breath, breath, all is breath.

Hymn transaction, traction.

Hymn long division.

Hymn contrition.

Hymn lost and found,

the boy-brother seven-mile endurance

down the Lake Street el-track canal.

Hymn the crayons I melted

on the 5th grade radiator and

drew side views of Lincoln

as a conjurement.

.

Hymn the parquet floor, the open door,

the growl, the yowl, the pirouette, the give-and-go,

the vestibule mosaic, the bathroom tiles,

creosote planks, the silhouette Stations of the Cross,

butcher-shop six-point star.

.

Hymn sorting, shedding, shredding,

staying the course,

rubber-ball hockey in the snow alley,

computing my Lexon League batting average, .119.

Behind the Signboards facing Washington Boulevard,

tall weeds, mush cardboard, jagged glass bottles,

dogshit, a single discarded Playboy, charred ——

impromptu boy battle, small rocks

into the weeds, out to the sidewalk,

one off my boy’s forehead, a glance, a graze,

no matter, but,

turning toward older girls walking past,

a scream,

my sweat transubstantiated

to blood mapping my face,

Rivers of the World.

Hymn Leamington Avenue.

Hymn Granville Avenue.

Hymn Lindell Boulevard.

Hymn Mullholland Drive.

.

Hymn your own streets.

Hymn your own cities.

.

Hymn Saint Louis.

Hymn Chicago.

Hymn Calabasas.

Hymn Momence.

The boy

turns away

from lines of children shoes and underwear

on the family board,

a numbers graph, an organizational chart,

looks out

to the curve of the earth,

to the broken glass morning glint,

to dogshit alleys,

to street grid lines leading away,

leading to puzzle and more puzzle.

I breathe puzzlement.

I am at the map

and can follow West End east to the Loop

or Maypole west to California, to China,

to Russia, to Europe, to New York.

I am on the map and fly

to the edge of all that is

and back to the Bang.

Hymn curb trash:

twigs, a leaf,

a mud-thick mitten from winter,

a rosary crucifix unlinked.

.

Hymn links and unlinking.

Hymn clouds of incense.

I will go to the altar.

Hymn clouds of leaf-burn smoke.

Hymn seedlings.

.

Hymn street cleaning.

Hymn no parking,

for sale,

loading zone,

no dumping.

Hymn don’t walk.

.

Hymn electricity.

Hymn tree cover, plumbing, two-flats,

six-flats, courtyard buildings,

the bungalow belt, the forest preserve clearing,

lagoon scum, the dainty fox through tombstones.

.

Hymn the asphalt street.

Hymn the gum, black on sidewalk concrete.

.

Hymn the elevated,

the elevator,

the elementary school,

the exit ramp.

Hymn photosynthesis.

Hymn sun soaking the red-brick wall,

my untranslatable scripture,

the word at the start and the end.

———-

Angels Are Out Tonight

Tonight, the typewriter keys slam rhythm

to ease coarse electricity under the skin.

.

The Sister of the Sacred Heart pleads alms

and sweats under her habit

as angels stride thickly east and west on her sidewalk.

.

Angels fly complex patterns

over the drunk anesthesiologist and the beautiful child.

.

Angels are out tonight.

.

The boy rocks his body right and left

to sleep

as angels whisper green forests in his ear

without mentioning the future gun,

a charity.

.

Angels are out tonight

as the fox scouts among the headstones,

as the sigh ends in stillness,

as Brother Pain is traded for Sister Death.

.

Tonight, angels are on the wind,

like a tune up the sidewalk,

like the white paint piers of the elevated,

like the ocean of police marching State Street,

Newman’s jolly coppers, the white-glove parade.

.

Down the court run fast-break angels,

in the chemistry moment,

actions and reactions,

without finish or start.

.

Angels are out tonight,

lining the beige nursing home walls,

and planless fireflies starscape the orphan shelter lawn.

.

Angels with assumed names

mingle the Cubs crowd tonight after a loss

and smoke Winstons outside the gay bar

and close up shop, lowering

the commercial-grade,

roll-down,

stainless-steel security door

with a thud.

.

Tonight, as the handgun rusts,

angels are out,

as ballerinas pirouette the Bible verse

along the red-brick wall,

as the sacristan eats his Filet-O-Fish,

as the lawyer in her sweats

stands on the suburban balcony

overlooking an industrial park

and tries to remember

the name of the kindergarten boy who vomited.

.

Angels are out tonight.

.

Angels embrace sorrow tonight,

finding storm within the storm.

.

They crowd tables in the Taylor Street trattoria,

drinking water and wine and breaking bread

before the elbow macaroni arrives, parsleyed,

the last supper of the night.

.

Angels run a marathon tonight along Lake Shore Drive.

Wearing orange vests, they dig a ditch with loud machines.

They sing gospel songs

and blues hymns

and country & western anthems

and Ubi Caritas.

.

In the sanctuary, a lieutenant kneels.

Angels echo in the high church space

along the stained-glass annunciation.

My soul magnifies, she said.

.

Angels are out tonight.

.

As I walk along Clark Street

through the cold night to apologize,

angels hide in the space behind the street lights,

and my sister balances

the weight of all that has come and all that

will happen, and my mother’s ashes are harmless,

and the aunt who saved my life

is willowy and curly blond still

in the backyard with the baby I was.

.

Latter-day angels tonight are out,

and bicoastal angels,

and special needs angels,

and glass-half-full angels,

Latin-rite angels,

strip club angels,

handyman angels,

service dog angels,

the heavenly host in mufti.

.

Tonight, the woman

wearing eight layers of pants and six shirts,

asleep in the tent on the Broadway sidewalk

amid metal restaurant tables and chairs

is with angels

swinging like the little girl she once was,

rising up,

swooping back,

legs building height,

and, at the top of her high, high arc,

she lets go

and flies up and out,

into the light,

the biblical furnace

where all pain is burned off like dross,

revealing pure.

.

At the alderman’s office, the precinct captain

takes the call and dispatches a crew of angels

to fill the potholes on a short street outside the ward,

through inattention or devotion or commotion or obligation

or corruption or inspiration or sedation or kindness.

.

Angels are out tonight.

.

The Pope works as a bouncer.

The Boston Celtic drives a hack.

A poem is written on the alley wall of a downtown hotel

in pencil on sooty bricks, never to be read.

.

And angels stir the coffee

in every cup on every table

in the hotel’s rooftop restaurant

and two miles away at the homeless refuge

and in the Mayor’s kitchen

and after the banker has said the rosary

and untouched between lovers

bending toward each other

and whispering, unknowing, the secret of breathing.

.

Angels are out tonight.

.

Michael and Gabriel, Uriel and Raphael,

Jegudiel, Selaphiel, Barachiel,

the thrones and dominations,

the cherubim and seraphim,

tonight amble the glittered Andersonville pavement

and climb the shadowed Englewood apartment stairs

and sit at the edge of dark in the Glenview yard

where a man who knows he is dying

barbecues for the ones inside,

each tock and tick mundane and solemn.

.

Tonight, angels sleep on the Red Line

from Howard to 95th and back and back and back.

.

Tonight, Tri-State Tollway motorists

barrel through the I-Pass lanes,

avoiding the tollbooth angels chanting the Daily Office.

.

Tonight, angels fall asleep in the ice-white television light.

Angels fight on the carpet

until Mom takes the plastic baby away from them.

Angels in the hotel room

can’t take their clothes off fast enough.

.

Angels are out tonight,

running around the university track,

each step an eternity, each exhalation another Big Bang.

.

In the Sovereign Tap, angels caress their Miller Lites

and watch Fred Astaire in The Royal Wedding

in between used car commercials.

.

Angels tonight await the Second Coming,

know they need,

know they want,

know they have no idea,

feel the high wearing off,

leave a backpack on the platform,

take an extra base,

twitch,

stalk,

run at the nose,

run on empty,

run to danger.

.

In the silence above the alleys,

angels are out tonight

as urgent rats,

worshipped in India,

revered in Rome and China and Old Japan,

jitter from hole to hole, the volted circuit.

.

Tonight, early drafts are put through the shredder

for no reason but delight at spaghetti-ed paper,

a dry meal of textured wonder and portent,

a gluten-free repast and echo of the halls of heaven.

…

The many Chicagos

There is a lot that I like in these poems. However, let me highlight the ending of “Towers Loom” as an example of what I’m trying to do.

I’m describing a walk that I took along Chicago Avenue with Sandra Cisneros, the author of House on Mango Street, one afternoon when I was interviewing her.

These lines deal with how the neighborhood drove her out of Chicago in the 1980s but now is the home of my son and daughter-in-law (as well as, since this poem was written, my three-year-old granddaughter Emma). Let me read that ending again:

A

right turn, and, in a mile,

Ashland, where, thirty

years later, I walked with

Sandra the grit Chicago that

abraded her out to the

southwest and Mexico and

back southwest again, talking

of the dust on medical

implements in the drug store

window, dowdy Rexall, and,

a decade later, my son and

his wife live there in a duplex

with two fireplaces and never

saw the Rexall, gone now.

They can walk to work in

the Loop in looming towers.

What I’m attempting to do here is to talk about the many Chicagos that layer every neighborhood, every street, every corner.

To explain things. To help Chicagoans and all people understand who we are and what it is that makes us tick.

….

Patrick T. Reardon

12.13.22

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.