The year is 1962, and a tall, drowsy boy opens the front door of his family’s crowded two-flat to the grey darkness of near dawn. The sidewalk along Leamington Avenue is empty as he heads the half-block south to the church. The neighborhood of cops, mechanics, firemen, cemetery workers, city workers, truck drivers and janitors is asleep. It’s a quarter to six.

The church is filled with a darkness that would be oppressive except that the sanctuary lights, turned on for this early weekday Mass, provide a welcoming warmth. In the back and near the side altars, banks of candles flicker.

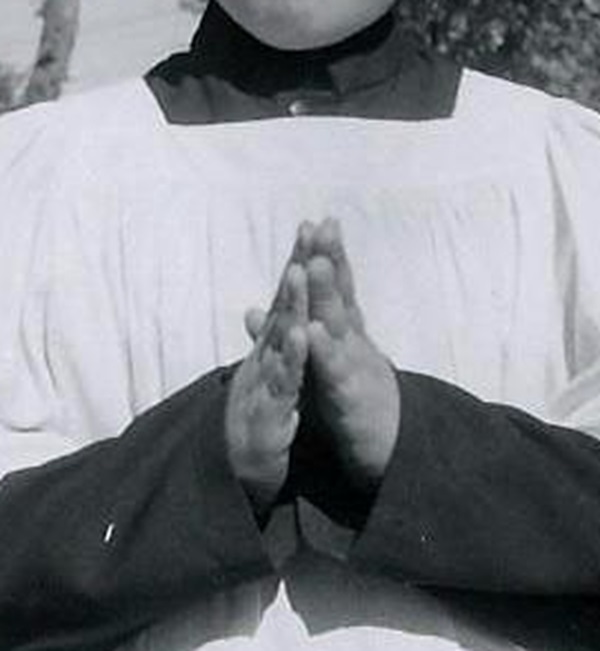

The boy goes to the door to the left of the altar and enters the sacristy. He selects a long, black cassock and works his way down the dozen or so buttons. Over this, he puts a plain white cotton surplice and walks down the corridor to the priest’s side of the sacristy. He fills one cruet with water and the other with wine, its over-ripe smell always a curiosity for him.

As the mass starts, Father Fitzpatrick places the green-draped chalice on the altar and returns to the foot of the stairs where the boy is kneeling. The priest, in his forest green vestment, turns to the altar, bows and, making the sign of the cross, begins:

“In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Amen. Introibo ad altare Dei.”

The boy, bent double, his head down nearly to the step in front of him, responds from memory in a rush:

“Ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meam.”

Something perfect in this moment

Later, at the Consecration, Father Fitzpatrick prays over the round, thin wafer of tasteless, paper-like bread, whispering the words of consecration with a dry, urgent exactitude. And, then, as the priest raises the newly consecrated Host, the boy presses a small keyboard on the step above him, creating five round, deep tones that reverberate through the silence and stillness of the church, all the way back to the vestibule.

There is something perfect for the boy in this moment.

He is kneeling in the midst of beauty, from the delicately colored terra cotta saints, angels and symbols set in the marble of the altar to the deep, rich, dark wood backdrop topped by even more saints, from the intricately worked lace altar linens to the gold thread and bright color of Father Fitzpatrick’s vestments. He is astonished at being so close to the wonder-filled richness of the altar, at being so near to the Host, at being a part of this central ritual of his community.

Like Peter, he feels the wish to set up tents and live here forever.

The Mass in context

Now, more than sixty years later, a tall, overweight man in his mid-70s walks up to the altar at Sunday mass to give the first reading from the book of Exodus and then returns to his pew on the far left side of the congregation. Something in the moment gets him thinking about the wonder he felt as an altar boy.

He saw the altar then as the focus of faith. Now, six decades later, he sees the Mass in context.

He has come to understand that faith is lived in the world amid the billions of other humans, or it’s not lived at all. Faith is a living thing, he’s learned. It’s not locked away, like a security bond, but shared in the rough and tumble of life.

And this rough-and-tumble life — a life of love and risk — is at the heart of the message Jesus brought. Jesus didn’t celebrate the Last Supper and then stay in the upper room. He went out to play his role in the drama of existence.

Having faith, the old man in the side pew has come to learn, is about being open to the fullness of life. He has learned this especially from his wife, and from their two children, both now adults with kids of their own.

Shares the messiness that is life

The altar is not a jeweled treasure, nor is it a hideaway. It is deeply a part of the world — like the airport, the grocery store, the house next door.

What happens in this place is not purer than what happens elsewhere in life. It shares the messiness that is life. It can be boring, yes, as an airplane ride can be boring. But it can be transcendent, too, as in the moment when you look out your window and watch a half dozen sparrows chitter around the bread crumbs left on the sidewalk.

And it is something that is done in and with the community.

The altar encompasses the entire world

Back six decades ago, the boy felt that he and Father Fitzpatrick were in a bubble of holiness. Now, the old man in the side pew knows that he shares this moment with all the other people in the pews, some of whom are his friends, others unknown to him.

The altar, in fact, extends out the full length of the church, and all of those present are taking part in the consecration of the host — and the consecration of their lives.

Even more, the altar extends beyond this building, beyond this city, to encompass the entire world. That is where the old man in the pew lives and where everyone else in the congregation lives. That is where the fullness of faith takes place.

At the store, in traffic, online, on a walk, in a crowd — in every interaction in life — this is where, like Jesus, the old man and everyone else gathered around this altar will play their role in the drama of existence. Holiness isn’t a bubble; it’s a smile.

Patrick T. Reardon

9.25.24

This essay originally appeared in the National Catholic Reporter on 9.13.24.

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.

Thank you for reminding me what Faith is. I remember being at that church looking at the altar boys looking at the priest.. We all need to be reminded that faith is everywhere. I absolutely loved This story.

Powerful and moving.