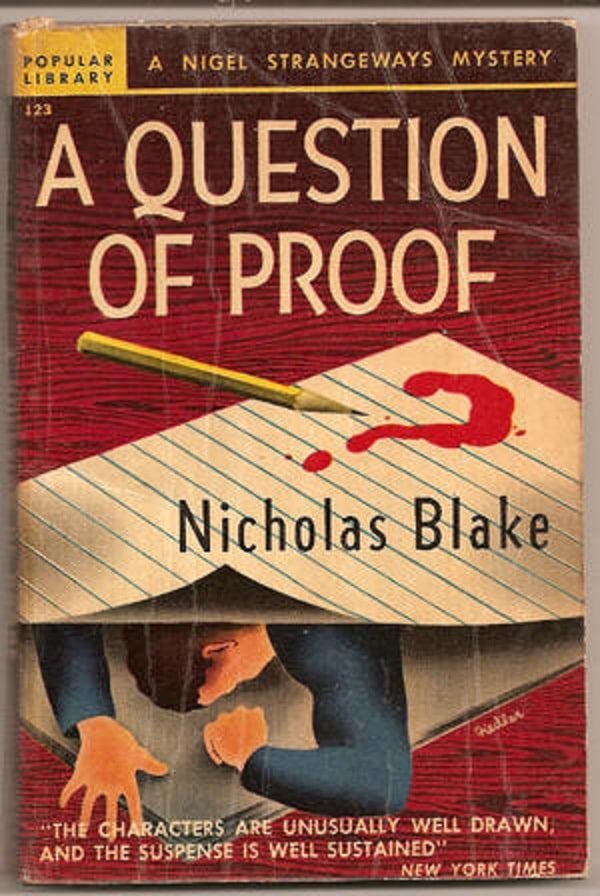

In 1935, Nicholas Blake published A Question of Proof, his jocosely told murder mystery and the first of sixteen novels which featured the gentleman detective Nigel Strangeways. Blake also published four stand-alone novels, the last of which was a much more serious and moodier work, The Private Wound.

That book arrived in bookstores in January, 1968, the same month that Blake took up a much more high-falutin job — as Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom — under his real name Cecil Day-Lewis.

Day-Lewis had a long and successful career as a poet and poetry teacher, publishing under his real name more than a dozen collections of verse as well as four books of translation, three essay collections, three novels for adults and two for children.

In modern times, however, poetry is rarely very lucrative, so it seems clear Day-Lewis turned to murder mysteries and popular novels as a means of beefing up his bank account.

“Degrade myself”

Indeed, he says as much in the early pages of A Question of Proof during a scene in which the lovers Michael Evans and Hero Vale rendezvous behind the high walls of a haystack.

Hero is married to Percival, the headmaster of Sudeley Hall, the English public school where Michael teaches English, and she’s saying she doesn’t want to ruin his career.

“My career!” Michael responds, going on to say even if he were prime minister or even poet laureate — a delicious little detail that Day-Lewis had no sense of three decades before reaching that summit — he’d be more than willing to ruin his career rather than live without her.

Yes, Michael has no money except his salary, but getting sacked in order to marry Hero wouldn’t be the worst thing, he says.

“After all, I’m not a halfwit. I’m sure I could get some sort of job. I might even degrade himself to writing novels.”

“You sweet, let’s hope it needn’t be as bad as that.”

“Ostrich-like strides”

Reading A Question of Proof more than nine decades after it was written, I had the sense that Day-Lewis was not so subtly thumbing his nose at his low-brow readers, even as he was hoping to cash in on them.

For instance, Nigel Strangeways is just plain outlandish.

Michael, who met Nigel at Oxford, tells Hero that Strangeways was so put off by the stuffiness of the place that, when it came time for final exams, he answered them in limericks:

“He’s a first-rate brain, but it alienated the dons, they have no taste for modern poetry.”

But that’s only the start of it. Michael explains:

“But you must have water perpetually on the boil; he drinks tea at all hours of the day. And he can’t sleep unless he has an enormous weight on his bed. If you don’t give him enough blankets for three, you’ll find that he has torn the carpets up or the curtains down.”

By this point, the two have arrived at the train station to meet Nigel. He’s a private investigator and the nephew of a high-ranking police official, and he’s come to help Michael who finds himself as the main suspect in a murder at the school.

The figure that emerged from a first-class carriage and advanced toward them with rather ostrich-like strides did not, Hero thought, live up to Michael’s lurid description. Nigel Strangeways blinked at her short-sightedly and bowed over her hand with a courtliness a little spoilt by the angularity of his movement.

“Guzzling his porridge”

And then….

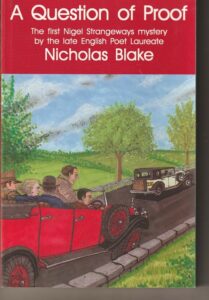

Well, then, there’s a car chase, of all things. (Agatha Christie never let such things get into her stories.)

“Follow that car,” the police superintendent yells as he gets into the car that Hero and Michael have used to pick up Nigel, and off they go chasing after a miscreant who did dastardly stuff….but, not, as it turns out the murder.

“Follow that car,” the police superintendent yells as he gets into the car that Hero and Michael have used to pick up Nigel, and off they go chasing after a miscreant who did dastardly stuff….but, not, as it turns out the murder.

That murder, by the way, was of a preteen boy, the nephew of Percival Vale named Algernon Wyvern-Wemyss. And, if the name wasn’t enough to prejudice the reader against him, Blake (Day-Lewis) introduces him this way:

A small, puffy boy of eleven years or so, with a vicious expression and the usual hallmarks of too much pocket money, is guzzling his porridge and tormenting his neighbor alternately.

Wemyss is choked to death on the afternoon when the school is having an athletic meet, his body later found at the haystack where Hero and Michael had spent time kissing.

“Swept down and swept away”

If Day-Lewis was approaching A Question of Proof as a literary lark, he, nevertheless, produced a story that flows nicely. His writing is uneven in tone, but, in a story like this, it carries the reader along.

A good writer almost can’t create really bad work. Indeed, there are moments when Blake sounds like the poet Day-Lewis is, such as the end of the car chase:

The Daimler went off at a tangent into the ditch. Her huge body pirouetted on its front wheels, was tossed up into the air like a toy, twirled over the hedge, and fell devastatingly into the field beyond, jerking clear a small black figure, a suitcase and several cushions, which came to earth scattered and severally, as though vomited out of a volcano.

That’s Blake the poet. Here’s Blake (Day-Lewis) the social critic:

Other persons, too, have come and gone, leaving the atmosphere still acrid and poisonous, as though after a gas attack; reporters from local and London newspapers, smelling out scandal for their titled proprietors like jackals scenting down a corpse for rather seedy lions.

Reporters with notebooks; reporters with telegraph forms; reporters with cameras, rather baffled to find no “sorrowing relatives” whose contorted features they may serve up next morning as a breakfast relish for their great public; reporters courteous, insinuating, truculent, well-meaning, ignoble, acute or obtuse — the whole swarm has swept down and swept away.

Some nice coin

Despite the uneven tone of A Question of Proof and the outlandishness of Nigel Strangeways and Blake’s (Day-Lewis’s) apparent mocking of the reader, the author got another fifteen novels out of the character.

He published at the rate of one every two years for the next three decades, and I would guess made some nice coin.

And, really, for all its flaws and quirks, it is a fun read after nearly a century from its writing.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.23.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.