It’s been fifty years since Robert E. Toomey, Jr., published his first novel A World of Trouble in 1973. It was also his last.

As I read the sci-fi adventure, set on a low-tech planet called Jsimaj, there were times when Toomey’s lack of any other publications was mystifying. And other times when I’d think, “Oh, I see.”

Toomey was clearly a writer of imagination and wit. In fact, a large part of the book involves a back-and-forth between Belakee Maes, an industrial spy on Jsimaj, and Peter Donovan, his brilliant, precocious and irritatingly immature thirteen-year-old pilot up on their company’s spaceship above the planet.

No on-off

This is funny on many levels, such as the usual teasing that goes on between work colleagues, except, in this case, one is on a planet facing strange and threatening situations while the other is safe as a bug in a rug up in orbit.

But Toomey added a dazzling wrinkle to the frequent sci-fi communication trope — Maes can talk to Peter through something implanted in his teeth, either verbally or subvocalizing when someone else is around, and he hears the pilot clear as day.

But he can’t NOT hear him.

There is no on-off switch. Peter eavesdrops on every conversation Maes has and on every interaction, such as a night of romance, and he talks to the spy so often and so regularly that Maes has to beg him to shut up.

Sometimes, Peter does.

On the plus side, when Peter is silent, he’s able to pump requested music to Maes as an aural background. Maes likes that.

Gapjumping

A World of Trouble is, as many science-fiction books are, a retelling of human history, in this case, the effort of one section of people to gain control over the lives of many other neighboring people.

What makes this case different is that a group of industrial bad guys, the Grefstyn, wants to take over Jsimaj for its valuable radioactives, and is violating cosmic law by supplying advanced technology to their allies on the planet — in other words, they’re tipping the scales using ahistorical methods.

Such people are called gapjumpers. They’re helping their allies jump a technological gap in the planet’s development. It’s a kind of cheating.

Maes is on the planet for the good guys, i.e., his company called CROWN, which also wants the radioactives but is stopping short of messing with technological development. Maybe on another planet they wouldn’t be such good guys.

On Jsimaj, the recipient of the new technology from the Grefstyn is an old, very decrepit, ambitious guy called the Derone. And the technology he’s getting include saddles with stirrups, crossbows and heat guns, i.e., the usual sci-fi ray guns. The Derone, by the way, is more than a bit over the top when it comes to sexual oddities as Toomey closely details.

Multipedes

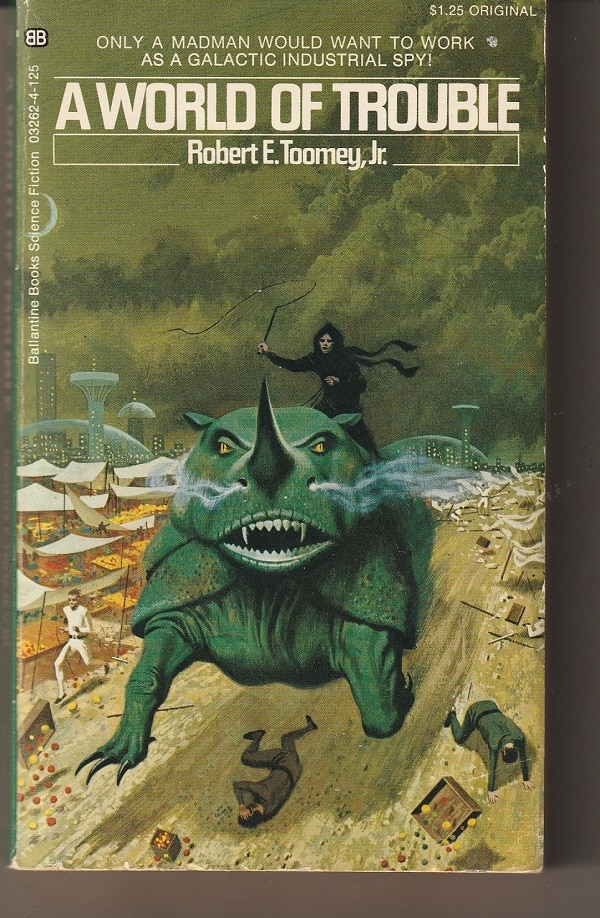

One of the best things about A World of Trouble is Toomey’s creation of the animals that end up wearing those saddles with stirrups — rendels, twelve-legged, armor-plated, fang-wielding multipedes.

A multipede looks like a three-way evolutionary draw between an armadillo and a dachshund and approximately two Clydesdales. Built low to the ground, they’re pale green and all armor, except for the speckled white belly. A full grown one is as high as a man’s chest and as long as a boring afternoon.

Maes has one named Pacesetter who is more than simply transportation for him. Pacesetter is his best friend. Toomey has imaginatively conceived the animal and the way that Maes has to use to show his affection. It’s enough to give the reader creeps but is touching as well. It involves stuffing his arm down the animal’s throat.

Faults?

That’s a lot of meaty and creative stuff for one novel. So why no more Toomey books? The best I can guess is that Toomey’s first novel had a couple of faults that didn’t make up for the good stuff.

For one thing, his story moves slowly. It lacks the snappy — or, at least, rhythmic — pace of a well-written book. Perhaps he got too hung up on his creative children to the point that he didn’t see the importance of the storytelling. Maybe there are just a few too many conversations between Maes and Peter.

The second thing is like the first. The story stumbles along for two hundred pages. And then ends.

It’s that abrupt.

The arc of Toomey’s story is basically only the center. He brings in a bit of the left hand part of the arc with two short flashbacks, but he has virtually no right hand part of the arc.

Maes is just going along, and then, well, the story’s over. This happens in the final pages, and loose ends are tied up, but there is nothing else to the conclusion except the conclusion.

I was sorry when I got that end. There’d been much in A World of Trouble that I’d like.

I wanted to like the end, alas.

Patrick T. Reardon

11.30.23

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.