More than 1,600 years ago, Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, wrote his Confessions, and it’s been a book with staying power. Indeed, as measured by its friends and enemies, the book — one of the key works of Christian theology and philosophy — has been important down to our present day.

Consider, as Garry Wills notes in passing in Augustine’s Confessions: A Biography, that Hannah Arendt, one of the most important political theorists of the twentieth century, wrote her doctoral dissertation on Augustine.

Wills doesn’t go into detail, but it’s easy enough to find out that Augustine’s Confessions and other books were highly influential to Arendt’s thought not only for her 1929 dissertation Love and Saint Augustine but also during the rest of her life. Arendt deeply mined the bishop’s ideas and experiences of love, including the great pain and loss he felt at the death of a friend.

By contrast, Friedrich Nietzsche, the influential nineteenth-century German philosopher, derided Augustine for overdramatizing scenes in his life:

“How psychologically phony — for example when he relates the death of a friend with whom he made up one soul, and decided to live on, since this way his friend would not be entirely dead. What revolting pretentiousness.”

As for Augustine’s extended examination of the sinfulness of a large, pointless theft of pears — “Such tear-jerking phoniness,” ranted Nietzsche.

In 1902, William James, in his ground-breaking psychological study The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature, declared Augustine “a classic sick soul.” Three decades later, Rebecca West, in the first psychobiography of the bishop, declared that his mother Monica emasculated him with Christianity:

“She did not want her son to grow up.”

Misreadings of Augustine

Hogwash is what Wills says to what he sees as misreadings of Augustine and his Confessions (although he says it in much more refined and sophisticated language).

Indeed, in the years right before and after the turn of this past century, Wills went on a bit of a crusade to help the modern world get to know the real bishop, writing at least seven books, including:

- Saint Augustine (1999) — one of the first installments in the Penguin Lives series in which the stories of great people are told by prominent writers and thinkers in a highly focused manner, aimed at capturing the essence of their importance.

- Confessions (2008) — a new translation by Wills for Penguin Classics.

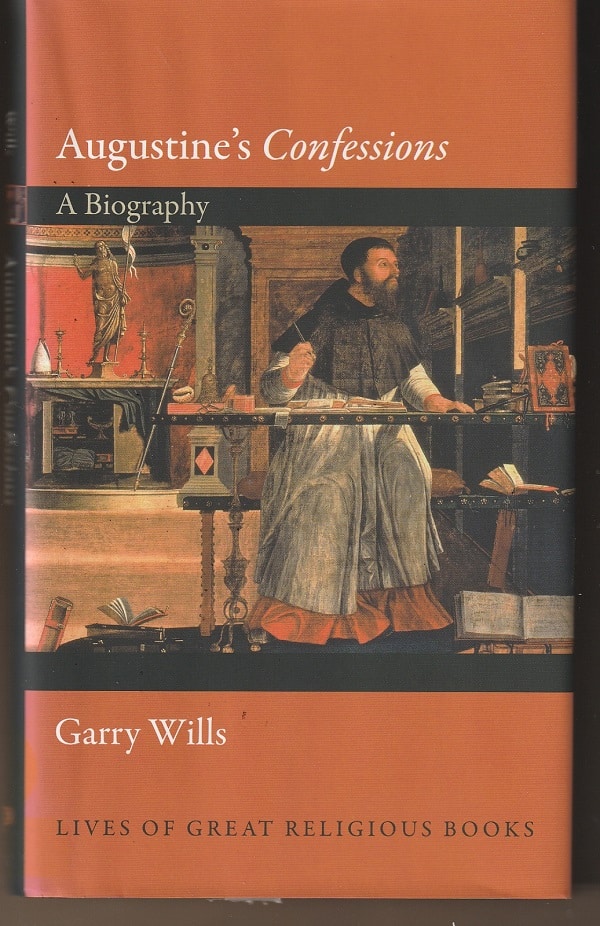

- Augustine’s Confessions: A Biography (2011) — an early installment in the stellar and sprightly Lives of Great Religious Books from Princeton University Press, a series in which each entry is written with verve and style by an expert for the general reader.

Wills is a public intellectual who writes often about U.S. history and politics as well as about religion, particularly the Catholic Church of which he is a proud member, even authoring a book Why I Am a Catholic (2002). So, Wills is examining Augustine and his works from the standpoint of an historian but also as a fellow-believer.

“Spiritual psychodrama”

In Confessions, Augustine told the story of his search as a young adult for an understanding of the world that made sense of all he saw, felt and experienced. It culminated in his conversion to orthodox Christianity.

Four years later, he became a priest because the church members wanted him in that job, and, five years after that, he was consecrated as bishop because he was such a good preacher. Then, one year later, “in a prolonged bout of dictation in the year 397 CE,” Augustine wrote the thirteen books of the Confessions.

It is a work, Wills writes in Augustine’s Confessions: A Biography, that “is commonly read as an autobiography — some even call it the first autobiography.”

But that’s wrong, he argues.

It is a prayer — “one long prayer, perhaps the longest literary prayer among the great books of the West.” Unlike an autobiography in which the author is speaking to him- or herself as well as the reader, Confessions is addressed to an audience of one, God.

[Confessions] relives the drama of sin and salvation, in the form of a journey toward God. It stands closer to Pilgrim’s Progress, or even The Divine Comedy, than to Rousseau’s Confessions. It is a theological construct of a highly symbolic sort….

We have to read Augustine as we do Dante, alert to rich layer upon layer of Scriptural and theological symbolism. We are not in the realm of autobiography but of spiritual psychodrama.

“Had ‘eaten’ the Scripture”

Augustine had memorized much of the Bible, and, in dictating Confessions, he writes in a manner in which his words and those of Scripture are “deeply infused.” Indeed, Wills notes:

Augustine, like Ezekiel, or like the John of Revelation, had “eaten” the Scripture and afterward thought in its terms and rhythms, with and through its words…

The sacred writings are present in Confessions not only when Augustine quotes them but in the way he uses his own words.

Augustine, for example, employs a most basic verse structure of the Psalms and of all Hebrew poetry — the two-line unit in which the second line repeats, reverses, or elaborates on the first one.

This pattern informs much of Confessions, its sighing replications, his way of turning a thought over and over. These give the book its air of slow reflection and inwardness. The words cast a spell and we are taken down into Augustine’s deepest self.

Thus, by a paradox, Augustine’s use of other people’s words (the sacred authors’) helps him speak most authentically as himself.

“Spelunking after God”

For a short book, just 148-pages of text, Augustine’s Confessions: A Biography is dense with ideas and insights, and yet not turgid. Wills writes in a way that is both sprightly and challenging. For instance, he notes that Augustine came to understand that God could only be found by introspection. “The light was within me, but I was outside myself.” In fact, as Augustine saw it, God was “deeper in me than I am in me.” Wills explains:

This is why he went spelunking after God.

That could have been the title of Augustine’s book — or of Wills’ book: Spelunking after God.

Throughout Confessions, Augustine is attempting to understand God by looking inside himself. By journeying deep inside himself, into his memory and experiences and feelings, he sees God in what he lacks, what he is missing, how he is incomplete.

And, sixteen centuries later, his journey still resonates.

Patrick T. Reardon

1.4.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.