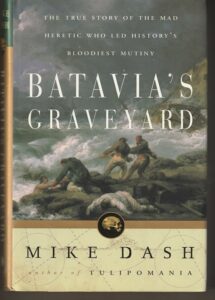

The hardcover edition of Mike Dash’s 2002 Batavia’s Graveyard has no subtitle. But, to attract potential buyers, these words are at the top of the dustjacket:

THE TRUE STORY OF THE MAD

HERETIC WHO LED HISTORY’S

BLOODIEST MUTINY

A year later, when the paperback was published, those words had become the book’s subtitle.

I mention this because subtitles can, at times, be dicey things, making promises that the book can’t deliver on. That’s not the case here.

Well, to be most accurate, let me say I can’t be sure about the “bloodiest” part. Dash doesn’t report how the body count in the slow-motion, two-part mutiny on the Dutch ship Batavia in 1629 compares with those of other famous or infamous sea-ship rebellions.

I am sure, though, after reading Batavia’s Graveyard, that Dash tells a true story with all its odd angles and edges about the Batavia’s mutiny and the psychopathic heretic, Jeronimus Cornelisz, who inspired and led it.

Truth be told, the paperback subtitle doesn’t go far enough to give a full enough glimpse at Dash’s account of the wildly improbable events on the Batavia and among its more than 300 sailors, soldiers, traders and passengers.

“A barren strip of coral rubble”

For one thing, the subtitle doesn’t mention the shipwreck of the Batavia in the mud flats off the coast of Australia, at a handful of the smallest, littlest, tiniest islets you’re ever likely to find, officially a small atoll that is part of the Houtman Abrolhos (Abrolhos Islands).

For another, it doesn’t mention that this was an uncharted spot in the Indian Ocean, far from the normal shipping lanes, far beyond reasonable hope of another ship passing near.

In a blinding storm, the ship wrecked in the early morning hours of June 4, slamming at full speed into the shoals off a spot of shale and guano that quickly became known as Batavia’s Graveyard. Dash describes it as

a barren strip of coral rubble, 500 yards long, less than 300 yards across, and roughly triangular in shape….It is low and flat and featureless and can be crossed from side to side in less than three minutes, or circumnavigated in a little under 20.

There are no hills, no trees, no caves, and little undergrowth; the highest point is only six feet above sea level; and…[its] soil is nowhere more than two feet deep. Most of the ground is nothing but shingle, slick in places with deposits of guano and treacherous to walk on.

Batavia’s Graveyard is home to thousands of seabirds and several colonies of sea lions but has no pools or wells or native animals.

It is dead, desolate, and utterly unwelcoming.

Not a happy ship

The treasure-laden Batavia, named for the capital of the Dutch East Indies, was not a happy ship, even before battering itself on the reef in the middle of nowhere.

Midway through the voyage to Java, Cornelisz, the second-ranking official for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) which built the newly commissioned ship and had weighed it down with goods, gold and silver for trading, hatched a plan with the skipper Ariaen Jacobsz.

They would take control of the Batavia from Francisco Pelsaert, the senior VOC trader and, as such, commander of the ship, and become freebooters, selling off its rich cargo and living the life of pirates preying on other vessels.

To accomplish their goal, they needed to spark a mutiny among enough of the sailors to get rid of — i.e., kill or throw overboard — Pelsaert and most of the soldiers guarding the treasure.

On a dark night, they incited several of the would-be mutineers to sexually assault Lucretia “Creesji” Jandochter, a young and beautiful married passenger who had spurned the advances of Jacobsz as well as Pelsaert. The hope was that Pelsaert would overreact and unfairly inflict heavy punishment on the entire crew, but he acted more temperately.

So, as the storm blew in the darkness of the early June morning, they were biding their time for another opportunity.

The only hope

Another thing the subtitle of Dash’s book doesn’t give any indication of is the Sophie’s Choice decision that Pelsaert had to make in the days after the Batavia ran aground.

In the shipwreck, 40 of the sailors and soldiers drowned trying to swim to shore, but 282 men, women and children survived, most on Batavia’s Graveyard and a lesser number, including Pelsaert, Jacobsz and most of the sailors, on an even smaller islet.

The people on Batavia’s Graveyard had no supply of water except rain, and none of the handful of islets nearby appeared to have any. The survivors were facing what seemed to be the certainty of a slow death from thirst and starvation.

Pelsaert and Jacobsz decided that the only hope was to try to save themselves and the best of the sailors by taking the ship’s longboat across the uncharted seas to Java.

And to leave four times as many of the survivors to fend for themselves.

“Across the open ocean”

There were few precedents for what the people from the Batavia were about to attempt: a voyage of about 900 miles across the open ocean in an overloaded boat, with few supplies and only the barest minimum of water.

Forty-eight people were jammed into the longboat, mainly sailors but also six without any expertise at sea, two women, a child and three men, including Pelsaert. Dash describes the longboat:

Forty-eight people were jammed into the longboat, mainly sailors but also six without any expertise at sea, two women, a child and three men, including Pelsaert. Dash describes the longboat:

She was quite a substantial craft — a little more than 30 feet long, with 10 oars and a single mast — but though her sides had been built up with some extra planking there was still not much more than two feet between them and the ocean’s surface.

The longboat continually took on water, there was an ever-present fear of overturning, and nothing sheltered the people from the sun.

Before long, one of the sailors in the boat confessed, “we expected nothing else but death.”

If the longboat could get to Java and alert company officials of the shipwreck, the expectation was that the VOC would send a ship to salvage the company’s boxes of treasure in the water near the wreck — and save anyone who had been able to keep themselves alive for the intervening three months.

The Lord of the Flies kind of experience

In addition, the subtitle gives no hint of the Lord of the Flies kind of experience that living on Batavia’s Graveyard and the other islets turned out to be for those left behind.

Through force of personality as well as his standing as the second highest company official, Jeronimus Cornelisz took over and ran Batavia’s Graveyard like a blood-thirsty bully. Each day for the people there was a constant dread of if and when Cornelisz’s toadies, mainly the would-be mutineers, would randomly decide to kill them.

Thirty of those left behind died from illness, thirst or drinking saltwater. Over the next three months and thirteen days, the rest were able to keep body and soul together by capturing rain and killing seabirds and sea lions.

But only as long as they were able to avoid catching the eye of Cornelisz’s henchmen.

Most weren’t.

More than a murder a day

Dash reports that, during the 101 days after the longboat left the atoll group, 105 sailors, soldiers, women and children were murdered by Cornelisz’s direct or general orders “by drowning, strangling, decapitation or butchery by axe.”

The only killing he attempted was the poisoning of a baby, and he botched it. The infant was strangled by someone else. Even so, Dash writes, Cornelisz had a psychological hold on his followers.

[Cornelisz] was, it seems, a truly charismatic figure — able to persuade a varied group of men that their interests were identical to his — and his talk of wealth and luxury that might yet lie within their grasp certainly made enticing listening for men trapped in the grey surrounds of Houtman’s Abrolhos.

Cornelisz was obviously and genuinely clever, and so vital that he stood out among the failures, novices, and second-raters who peopled the Batavia’s stern. He was also self-assured and eloquent in a way that awed men who were neither.

“A seducer of men”

The plan of Cornelisz and his followers was to capture the rescue ship, if one ever came, and use it for piracy.

But, on September 17, when the Sardam, a small merchant ship, arrived with Pelsaert in command, the mutineers were in the midst of a battle against the one group of survivors who had endured, away from Batavia’s Graveyard, on an islet where they discovered wells.

Told of the reign of murder that Cornelisz had led, Pelsaert conducted a detailed investigation and then trials. And seven of the mutineers, including Cornelisz, were sentenced to be hanged on Seals’ Island.

Cornelisz tried to escape the noose through poison, but he botched it. He raved in agony for many hours from the pain. And then, on October 2, 1629, Cornelisz was the first to be hanged. A minister who watched said:

“If ever there has been a Godless Man, in his utmost need, it was he; [for] he had done nothing wrong, according to his statement. Yes, saying even at the end, as he mounted the gallows: ‘Revenge! Revenge!’ So to that end of his life he was an evil Man.”

The mutineers described him as “a seducer of men.”

Capturing every amazing aspect

The story of the Batavia, its shipwreck and the imposition of Cornelisz’s bloody and demonic reign is amazingly complex, and, in Batavia’s Graveyard, Dash does an expert job weaving together all the complicated aspects of his tale.

Some American readers are likely to have difficulty keeping straight all the many people who have what seem like strangely odd Dutch names. Yet, Dash does about as well as could be expected to make clear at each point who is who.

Some may find the 23-page epilogue detailing the later life of many of the important and not-so-important characters in the Batavia saga as too much of a good thing. Even so, it is a reminder that this amazing experience was just a chapter in the lives of those who survived the ordeal. Just as they had had a life before boarding the ship for Java, they had one after finally getting to Java.

The Batavia story is an astonishment. And Dash’s book captures every amazing aspect of it with sureness, clarity, hard facts and deep perspective.

Patrick T. Reardon

3.9.24

Written by : Patrick T. Reardon

For more than three decades Patrick T. Reardon was an urban affairs writer, a feature writer, a columnist, and an editor for the Chicago Tribune. In 2000 he was one of a team of 50 staff members who won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. Now a freelance writer and poet, he has contributed chapters to several books and is the author of Faith Stripped to Its Essence. His website is https://patricktreardon.com/.